Before being appointed as ouvidor, Manuel José Baptista Felgueiras had served the Portuguese crown as juiz de fora in two small municipalities in mainland Portugal. For a newly qualified lawyer like him, the position of juiz de fora was the usual point of entry into the magistracy, followed by the post of ouvidor/corregedor, higher up the judicial hierarchy, and culminating in a seat on a high court as desembargador.

On October 30, 1801, the expected appointment as ouvidor came. It was, however, located in a remote and minor jurisdiction in Portuguese America: Espírito Santo. These overseas posts were virtually a mandatory step in every typical judicial career – and may even have provided a shortcut to the highly coveted seat on the Casa da Suplicação, the Portuguese Court of Appeal. This was the case with Manuel José. His loyal services overseas were duly rewarded, with an appointment not only as desembargador when he returned to Portugal, but also as deputy of the Mesa da Consciência.

In moving from one jurisdiction to another, and particularly when serving in remote and often isolated posts, judges had to carry everything they needed with them, as things would have been very hard to come by locally. What a Portuguese judge of the late 18th century needed most was books. Thus, on April 30, 1802, shortly before embarking, the newly appointed judge petitioned the Crown administration, asking permission to carry with him eight books. Permission was granted and the books were duly shipped.

Thanks to the control that the Portuguese Crown exercised over the circulation of written material, it is possible for us today to know exactly which books an itinerant magistrate, such as José Manuel, took with him when assigned to an overseas position on the eve of the liberal era. The present study examines eleven lists of books made by magistrates assigned to judicial positions throughout Portuguese America in the late 18th century as a way of shedding light on the kind of normative information these judges needed for their work overseas. This study attempts to ascertain which books were especially ›useful‹ for travelling judges, which genres were considered suitable for these professionals, and whether these libraries differed from stationary ones.

Books have been extensively studied by legal historians, but the focus has mostly been on their content. Scholars of the history of legal thought often studied books without paying much attention to them as concrete material objects1 whose production and dissemination in fact constitute a multifaceted collective endeavour, involving a multitude of individuals extending far beyond the individual authors.2 The approach adopted here thus attempts to include the study of books as physical objects in legal history, considering the book as a printed medium – bulky yet fragile – and relating book ownership to judicial practice. Developments in the field of book history are thus key to our approach.3 Legal history is essentially a textual enterprise: a field that works on legal texts.4 Generally speaking, normative information5 can circulate and be transmitted by way of various spheres of communication. It can be shared orally, yet the literary tradition – in the form of either printed material or manuscripts – predominates. Within this tradition, books are the main means by |which legal texts have been transmitted, especially with regard to the ›scientific‹ law cultivated by learned lawyers.6 As Hespanha reminds us, this object ensured that the knowledge of erudite law reached the most distant locations, even where no individual with legal authority was present.7 Hence, viewing law books from a different kind of perspective, as law books in motion8 and as objects in which normative information is stored, may shed valuable light on how the global circulation and translation of normative knowledge took place within the Portuguese empire, and how this came to engender a legal regime of such extensive reach.9

The article begins by describing the complexity and vast extent of the Portuguese system of justice in the 18th century. This was largely a consequence of the pluricontinental distribution of judicial positions. In the second section, the careers of eleven letrados (›lettered‹ or ›learned‹ jurists, that is, those who studied law at university) who were appointed ouvidores in Portuguese America between 1799 and 1806 are used to illustrate the Portuguese judicial apparatus. In this period, the circulation of written materials was controlled by the Crown, obliging judges to seek authorization to carry books with them. The third section therefore is dedicated to describing the censorship sources that allow us to identify the collection of books that accompanied each judge when he travelled. Finally, in the last section, an analysis of these book lists leads us to the conclusion that these collections of legal books comprised what I will call travelling libraries: portable collections of professional books indispensable for work in overseas jurisdictions.

The Portuguese Empire had no general model or uniform strategy in terms of imperial political administration of its widely dispersed dominions.10 Structures of government in the colonies had to be adapted to local conditions, resulting in a complex mosaic of distinct jurisdictions. Trading posts and medieval institutions like seignories, where a nobleman ruled by way of delegation, coexisted with areas under central control, occupied and governed by officials in the service of the king.11 In these more stable land holdings, such as those in Portuguese America, the traditional structure of government – including the administration of justice – had been to some extent replicated,12 notwithstanding a number of concessions to local peculiarities.13 Shaped by a corporative conception of society, these dominions ended up reproducing a constellation of decentralized powers, in which the power of the Crown was in constant competition with local interests.14

In this context, the most visible face of the imperium – and indeed, its main function in the Ancien Régime – was the administration of justice. This means that delivering justice was accorded high priority in the organization of society. Though designed to resolve conflicts, the judiciary itself could constitute a motive for power disputes, largely in consequence of its being structured as a multiplicity of disparate semi-autonomous local bodies sharing power and yet subordinate to the jurisdiction of the Crown. At the lowest level, jurisdiction was mostly exercised by a lay member of the local elite elected by the municipal council (juiz ordinário), but in exceptional circumstances, it could also be conducted by a law graduate appointed by the Crown (juiz de fora).15 Immediately above these, with geographically broader and hierarchically higher jurisdiction, there were magis|trates chosen by the local ruler, ouvidores in places where a donation system with seignorial jurisdiction still prevailed, or corregidores appointed by Lisbon in places where the jurisdiction of the Crown held sway. Broadly speaking, this arrangement persisted throughout the Ancien Régime. This was true even in the 18th century, which saw a rapid expansion of the judicial system in Portuguese America into the vast Brazilian interior16 alongside growing restrictions on the powers of the local land holders. In consequence, most of the seignorial judges were replaced by royal ministers – although, in Portuguese America, the term ouvidor was used indistinguishably for both royal and seignorial judges.17

In the delicate balance of power between local autonomy and Crown intervention in a colonial domain, magistrates appointed by the Portuguese Crown were supposed to tip the balance in favour of the interests of the king.18 The procedures involved in the career of a magistrate provide clear evidence of this, and it was especially true in the late 18th century, when magistrates constituted the driving force behind centralization within an imperial policy oriented towards integration.19 In the first place, progression in the career of a magistrate depended on royal appointment,20 and a certain loyalty to the king was therefore expected. Second, the purpose of three-year appointments was to prevent the establishment of local ties. Likewise, an attempt was made to circulate magistrates around the various Portuguese dominions, appointing them to a succession of remote posts until they attained the coveted position of desembargador, the highest rank of a judicial career. At least, this was the intention of the Crown. In the distant reality of the colonies – a distance that was not just the result of spatial separation – the defence of Crown interests that the circulation of magistrates through a variety of temporary posts was aiming to achieve may not have been forthcoming. The autonomy and self-regulation of the administration of justice overseas21 and the openness of the ius commune to the specificities of the colonies could lead to a centrifugal distribution of power that worked against the intentions of the Crown.22

Despite the multifaceted structure outlined above, the judicial body could be perceived to be homogeneous in terms of the formal education it received. With a few rare exceptions of individuals being trained at Salamanca or Bologna, all judges were alumni of the University of Coimbra, which provided standardized instruction. This uniform background and the very institutional architecture of justice provided a certain unity regarding the law in all the territories that made up the Portuguese empire. The Ordenações Filipinas in force in Portugal and the vast written tradition of the ius commune were also applied overseas. Of course, the manner in which this vast body of normative literature was in fact interpreted and activated in the colonial context could vary, principally as a result of the characteristic plasticity of the ius commune.23

In short, the Portuguese administration of justice functioned through a complex and pluricontinental network of judicial posts24 in which magistrates were empowered by their offices and established as a homogeneous class circulating beyond the confines Europe25 and operating as mediators between royal interests and local claims, or even on their own behalf.

By the second half of the 18th century, in an attempt to impose a greater structure on the judicial system in Portuguese America and shore up |the authority of the Crown in all parts of the empire, the number of judicial posts was increased with the creation of new comarcas and ouvidorias (judicial districts) by the Desembargo do Paço (the highest court and administrative body). The consolidation of the Crown’s political and judicial apparatus resulted in many magistrates being appointed to serve in Portuguese America, including the eleven men of letters examined here, who crossed the Atlantic with their books to practice what they had learned in Coimbra between 1799 and 1806.

As the designation lugares de letras makes clear, these judicial positions were restricted to letrados,26 i.e. those who had graduated in civil or canon law, usually from the University of Coimbra, the only university in the Portuguese world. Judicial posts (juiz de fora, ouvidor, desembargador) were distributed across the pluricontinental empire without strict or formal distinctions being made between metropolitan and overseas posts. The concept of network is often used to describe the tangle of sea routes and trade posts of which the dynamic Portuguese empire was composed.27 The metaphor is also useful for describing the architecture of the Portuguese administration of justice, not only in so far as it included judicial positions in a wide variety of different locations geographically very distant from one another – such as Goa, Angola or Rio de Janeiro – but also as they involved intensive circulation of individuals from post to post. While a nobleman resident in Spanish America could graduate in leyes or cánones and then hold a judicial position without ever having to cross the Atlantic, a subject of the Portuguese empire born in the colonies would invariably have to move continents in order to become a magistrate.28

Put simply, the life of a Portuguese magistrate was marked by mobility. The careers of the eleven magistrates examined here amply exemplify this. The following table provides information on a) their birthplaces, if they were reinóis or »filhos da terra«;29 b) whether they had studied canon law or civil law at Coimbra, and the year they completed their studies; and most importantly, their assignments and allocations in the service of the Portuguese Crown, in particular c) what posts they held before d) being assigned as ouvidores in Portuguese America, and then e) how their careers progressed. Later, this prosopographical analysis will help us to understand the kinds of libraries they used for their work.

The table shows that five of the magistrates were born in Portuguese America,30 yet none of them were assigned to their respective birth towns. This practice was avoided by the Crown, especially in the case of first positions in a judicial career, to prevent the establishment of client networks through which social capital could exercise greater influence. Of the five, four reached the highest judicial post of desembargador, three of them in Portugal. This suggests that there was no discrimination on the basis of geographical origin.

The three-year duration of each judicial appointment determined the rotation of appointments around the pluricontinental network, resulting in an intensive circulation of personnel. Even in such a small sample of eleven judges, the mobility intrinsic to the Portuguese magistracy is clearly evident. A magistrate would have to assume posts in different places, often overseas, in order to progress in his career. Most of the magistrates included in the group examined here had served at least once as first-instance judges on the peninsula by royal appointment before being appointed ouvidores in Portuguese America. The one exception – João Baptista dos Guimarães Peixoto – had been given the post of prosecutor, a function usually exercised by local lawyers under royal authorization. The position of ouvidor therefore required previous experience, preferably in a location other than one’s new appointment. |

Service overseas was frequently viewed with trepidation by magistrates. The journey could be daunting and the colonies could pose a multitude of difficulties. To compensate for this, the Crown encouraged judges to take up posts in remote parts of the vast Empire by rewarding them with a career jump, offering a position on the highest courts in the land immediately after having served overseas.32 Indeed, nine out of the eleven magistrates examined here were subsequently promoted to the position of desembargador – a lifetime appointment. Modesto Antonio Mayer, meanwhile, was appointed to the equally prestigious – and profitable – position of Intendente dos diamantes, also reserved for letrados. Its holder was responsible for the inspection and supervision of the mining and |trading of diamonds in an effort to suppress smuggling.33 Only Gregorio José da Silva Coutinho left royal service entirely on relinquishing the post of ouvidor. He nevertheless was granted a sugarcane mill as a sesmaria (royal donation) in Paraíba and subsequently settled there.

For the most part, therefore, magistrates did not stay put in the locations where they served. These positions were only temporary stopping posts on the way towards further promotion. In addition to there being no intention of settling, the appointment might furthermore be situated in a remote location. Some were on the coast – Rio de Janeiro, Espírito Santo, Ceará – and, in these cases, goods were more readily available. Others, however, could be very remote – such as the Brazilian sertões, where a significantly restricted variety of European goods arrived with far less frequency. To give just one extreme example: Caetano Pereira Pontes was assigned to the judicial district of São José do Rio Negro in the heart of the Amazon rainforest. Its main town, accessible only by river boat, in 1773 had a tiny population of approximately two thousand inhabitants.34

Books were quite scarce in Portuguese America.35 In contrast to the Spanish colonies, the strict Portuguese policy of maintaining dependency on the metropole prevented both the foundation of universities and the establishment of printing presses.36 The market for books was confined to larger cities, such as Rio de Janeiro, Salvador and Olinda, and books were often sold by merchants alongside other goods. Where convent libraries existed, judicial officials could also resort to those. In fact, some convents had the largest libraries in Portuguese America,37 usually including an extensive collection of law books. Some places, however, had no library at all.

Due to this uncertainty regarding the supply of books, magistrates needed to have all the material they required already prepared before they took up the post. No matter where the judge was assigned, he was better off taking his own books with him than trying to find them in the colonies. However, as will be explained in the next section, authorization was required to carry books within the Portuguese empire.

During the Pombaline period, known for its enlightened reformism,38 the Portuguese government institutionalized secular censorship to monitor the diffusion of ›correct‹ ideas, controlling both political and religious content, and consequently suppressing or amending seditious and subversive works. Hitherto, censorship in Portugal had been carried out by a trio of institutions: the Portuguese Tribunal of the Holy Office, the Diocesan Ordinary and the Desembargo do Paço.39 However, in 1768, the Marquis of Pombal ordered the creation of the Real Mesa Censória, which was to be responsible for controlling and authorizing the printing, sale and transportation of books.40 In contrast to most Catholic monarchies in Europe, where censorship had been exercised concomitantly by a variety of different institutions – such as the universities or the Church – the Portuguese Crown henceforth monopolized censorship41 to the exclusion of any other power.42 This was all part of its agenda of political centralization.

The broad-ranging duties43 assigned to the Real Mesa Censória included the control of the circulation of ideas. Every piece of writing, be it a printed book or a manuscript, needed the censor’s approval in order to be shipped anywhere in the pluricontinental Portuguese Empire, even from one city to another within the peninsula, regardless of whether it was for sale or private use. In short, whether books were destined for Macau, Goa, Luanda, Cabo Verde or Rio de Janeiro, a request had to be submitted to the Real Mesa Censória, which would subsequently check each volume |against the Index of expurgated books and the lists of books forbidden by the government.44 It is precisely these lists of books submitted to the Crown censors that constitute the principal sources of information on these magistrates’ travelling libraries.45

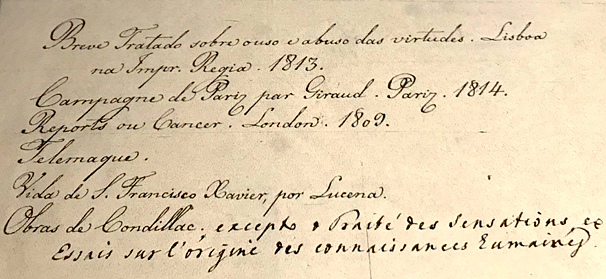

The first observation that should be made regarding this kind of source is that, since censorship is involved, books widely known to be banned were unlikely to be included in the lists submitted to the censor.46 Examination of the lists reveals very few cases of authorization being refused. In other words, so far as the control of circulation is concerned, the ›censors at work‹ remained largely unseen. On those rare occasions when a forbidden book was found on the list by the censor, the entry was marked with an X – or more uncommonly, an annotation – and the request was granted with the following proviso: »concedem licença para os que não forem proibidos« (»a licence is granted for those [books] that are not prohibited«). This was the case with the excerpt from a list reproduced below. The censor has annotated the entry Obras de Condillac with the words »excepto Traité des sensations […]«.47

An overall assessment of the documents indicates that regulations could vary over

the years. For example, one of the magistrates studied here, Joaquim Teotonio Segurado,

experienced no difficulty shipping a copy of La Scienza della legislazione by Gaetano Filangieri to Goiás in the Brazilian interior in 1804.48 However, an attempt by a trader to ship the same book to Rio de Janeiro in 1817 did

not enjoy such leniency.49

This example brings us to another observation. Some individuals may have received privileged treatment when requesting permission. All of the eleven magistrates studied here, without exception, emphasized in their requests that they had been appointed to the post of ouvidor. This is only to be |expected in a hierarchically stratified society such as that of the Portuguese Empire in the final years of the Ancien Régime.50 This could constitute a signal to the censor to treat their applications differently. In fact, most forbidden books were not completely banned and the rules did not apply to everyone. Generally, there was a concern that censored material should not reach members of the general public, who could misinterpret some ideas, but such material could be read by enlightened educated men.51 By the same token, the Real Mesa Censória could grant concessions regarding reading matter. Control over the books owned by magistrates in the service of the Crown could therefore be more flexible. This would also explain why the lists made by magistrates are generally less comprehensive than those compiled by booksellers, who often also included the year, size and place of publication.52

The care taken in writing these lists brings us to the last observation regarding this source: the lack of information that makes it difficult to identify the precise edition.53 Sometimes only the author is listed, while other items are listed solely by the title, as can be seen in Figure 1.54 One interesting case is that of the Manual prático judicial, cível e criminal by Alexandre Caetano Gomes, first published in 1748, which is the third most commonly cited title, appearing in seven out of ten libraries. Although no entry expressly mentions the author, it can be identified by consultation of studies on the legal literature of the period and bibliographical works.

In short, the booklists shed valuable light on the circulation of normative information, so long as they are assessed using a methodology that takes into account and is supported by works of reference that provide accurate identification of the books listed. In the present study in particular, these booklists provide new insights into the circulation of men and their printed material, revealing how the one is intimately entwined with the other.

Jeronymo da Cunha, in Arte de Bachareis, ou Perfeito Juiz,55 a short deontological manual intended for judges taking up their first positions, devotes a whole chapter to providing an account of which books a judge should possess.56 He starts by noting that common opinion considers that the larger a magistrate’s library, the better. Cunha, however, argues the exact opposite to be true: to him, utility is more important than quantity. As outlined above, mobility was an intrinsic feature of a Portuguese magistrate’s career. Cunha reminds his readers of this and argues that, when choosing books, one must take into account, as he puts it, the »gypsy life« of a Portuguese judge.57 The temporary nature of overseas posts was one reason why a magistrate might be reluctant to move all his belongings. Besides, books were expensive, heavy and fragile.58 Cunha also warned that books could get lost or damaged with all that frequent travel, and this is why he recommends »only a few and good books«, or, as the marginal note of this section says: »he should select the best«.59

While there was no limit on the number of books a magistrate might keep in his stationary library, travelling libraries were usually relatively small. Such a small collection of books could be transported without much effort. According to Camarinhas’ study of the stationary libraries of Portuguese magistrates at the time of their death, |over the same period, these contained an average of 145 titles, around five times more than the average of 27 found in the eleven travelling libraries studied here.60

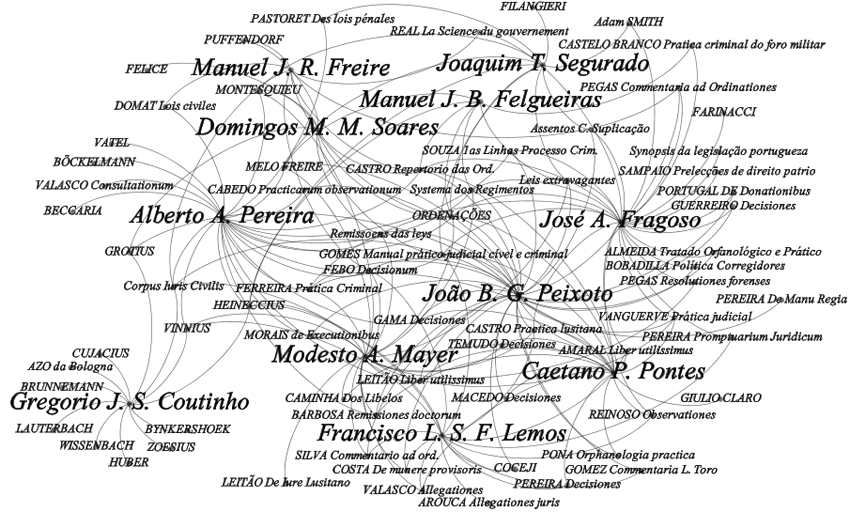

Comparison of the book lists of these eleven ouvidores in the form of a network analysis shows how these relate to each other and reveals the most important items of a magistrate’s travelling library. Figure 2 illustrates the points where the magistrates’ libraries overlap, using a sample of seventy titles.

This diagram attempts to represent visually a two-mode network, showing connections

between two distinct sets of entities: titles and magistrates. The dots and lines

show the relationships between books and their respective owners: larger fonts indicate

the magistrates, smaller ones the book titles, while the lines represent ownership.

In this network, the closer to the centre a title is situated, the more frequently

it appears in the magistrates’ libraries. Those that appear in only one collection

thus tend to be located on the margins. For the same reason, libraries that have more

books in common tend to conglomerate, while those with fewer interactions are spaced

further apart.

The most striking feature of this network – which renders this approach highly useful

– is that the book lists share many titles in common, with the exception of that of

Gregório José da Silva Coutinho, who appears on the far left of the diagram, largely

detached from the others. As mentioned above, the ouvidor of Ceará was the only one who subsequently left the legal profession, becoming a

senhor de engenho in Portuguese America. In addition, his collection of books was not a travelling

library but a shipment of volumes to a stationary library already in existence at

the location. The titles in this collection do not include the legal books typically

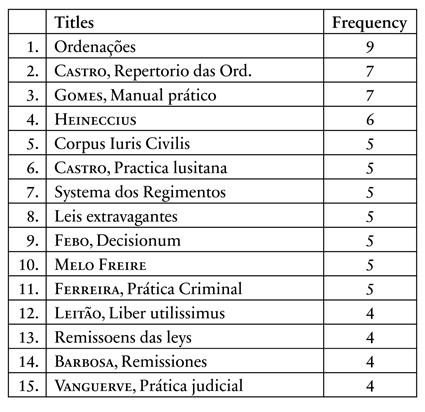

used by magistrates, as the following table presenting the fifteen most commonly occurring

titles demonstrates.

As a general rule, travelling libraries aimed to include only the essentials and left out any material deemed superfluous. This explains why these collections contained predominantly legal titles. In a few cases, history books and Latin, Portuguese, French and even English dictionaries were included – these being present in five of the collections. Religious books, on the other hand, are almost entirely absent, and, so far as belles lettres are concerned, only José Albano Fragoso allowed himself the luxury of some poems by Bocage. The content of these lists is thus predominantly professional in character, with each book serving as a work tool for the magistrate.61

This preference for a »few good books« also governed the choice of specific legal books according to the genres of legal literature available during the Portuguese Ancien Régime: commentaries on the Ordenações, casuistry literature (mostly decisiones), manuals on forensic and notarial practice, legal repertories and other reference works, and finally some specialized monographs.62 A magistrate’s travelling library needed to include at least one copy of each genre, but he could not afford to include many of the same type. That being so, a judge would definitely need one work of commentaries on the laws of Portugal. Alberto Antonio Pereira and Caetano Pereira Pontes selected the traditional Remissiones Doctorum,63 José Albano Fragoso chose Pegas’ Commentaria,64 while Francisco Lopes de Sousa Faria Lemos preferred a more up-to-date version of Pegas produced by Manuel Gonçalves da Silva.65 The same goes for forensic and notarial practice – that is, books relating to procedural issues. There was no point, for instance, in transporting both Orphanologia practica66 and Tratado Orfanológico e Prático.67 Caetano Pereira Pontes chose the former, while José Albano Fragoso opted for the latter.

Casuistry books exhibit a slightly different pattern. While the praxis regarding orphans was the same in both of the aforementioned books, each collection of decisiones – works of legal doctrine commenting on the decisions and precedents handed down by a high court, usually the Casa da Suplicação – provided different sets of decisiones.68 Of the various collections of decisiones available,69 the magistrates usually picked two or |three. Belchior Febo70 was the author most commonly selected, appearing in five libraries, usually in combination with other titles. This was the case in the library belonging to the ouvidor of Espírito Santo, Alberto Antonio Pereira, who opted for a combination of Febo, Gama and Cabedo.71

The title appearing most frequently was unsurprisingly the Ordenações do Reino, followed by the Repertório das ordenações by Manuel Mendes de Castro,72 included in seven out of eleven travelling libraries. These repertoires and other reference works were indispensable tools for the jurist of the Ancient Régime, since they attempted to confer some order on the dispersed and complex royal legislation, doctrinal authorities and estilos das Cortes with the aid of an analytical subject index in alphabetical order.73 This is the case, for example, with the Liber utilissimus judicibus, which was included in four of the libraries. As the title indicates, this volume was moving towards a more pragmatic approach: providing ready-to-hand condensed normative knowledge.74

The clearest example of this type of literature75 is probably the Manual practico judicial, civel, e criminal.76 The book was compact – comprising just 270 pages of civil and criminal procedures for both ecclesiastical and secular jurisdictions – and easily readable –written in the vernacular and providing succinct, simplified guidelines. As is usual in pragmatic literature, the prologue addressed the intended readers.77 These were ordinary judges and judicial officials who were not letrados but nevertheless had to deal with matters relating to the law.78 Despite this, it was the third most commonly found title, selected by seven of these learned and experienced magistrates for inclusion in their travelling libraries. Unsurprisingly, its transportability – one quarto volume – and compactness made it an ideal book for a travelling library.79 These features of pragmatic literature were of especial importance in the frontier regions of the Empire.80

The aforementioned titles were part of the literary tradition of law in the Portuguese Ancien Régime. In general, this accorded with the lists of recommended books found in deontological manuals.81 However, most of these were written and published in the 17th century, still under the influence of the ius commune. Despite persisting until the 19th century, the literary tradition of the Ancien Régime was already in decline by the mid-18th century.82 This corpus of literature, based on the auctoritas of communis opinio – increasingly criticized by Enlightenment authors – subsequently had to share the shelves of libraries with literature that advocated the consolidation of the authority of the Crown. Books such as the aforementioned Remissiones Doctorum, which reformists disapproved of for their lack of method and system,83 could thus be found alongside copies of the compendium of Elementa juris civilis by Heineccius,84 known for its ›axiomatic‹ method.85 The latter was, in fact, the fourth most commonly featured title in the collections studied here, being present in six libraries. The main proponent of this tendency in Portugal and clearly associated with the usus modernus pandectarum was Pascoal de Melo Freire,86 whose work could not fail to be present in the libraries of the late 18th century. In fact, this author’s name appeared in half of the book lists. Three copies of the official collection of assentos87 in the magistrates’ libraries provide further evi|dence of this movement towards the centralization of power and monopolization of law by the Crown.

The composition of these libraries in fact clearly signals the transition that would irrevocably lead to the liberal state and its codes. It is, however, a microcosm. A travelling library was thus the perfect distillation of the stationary library: a miniature version of the corpus librorum. Its requirement of portability necessitated the inclusion of a reduced number of books, but the essentials were always included. Far from being a mere collection of books moving from one spot to another, this was a judge’s toolbox, and, like any good toolbox, it had to contain the tools the judge would need to apply the law wherever in the pluricontinental Portuguese empire the Crown might send him.

The widely dispersed territories that made up the Portuguese empire were governed by a highly complex global legal regime. Among the multitudinous layers of jurisdictions and normative orders within this regime, secular justice occupied a prominent position. In the 18th century, letrados appointed by the Crown moved around a network of judicial posts on multiple continents, from Goa to the Amazon rainforest. These men brought with them a continuous stream of normative information, stored in and transmitted through printed media. The present article has examined one part of the dynamics of this global circulation of normative information: namely the official one, involving the Crown. Knowledge of the extent and type of normative knowledge available to the magistrates operating in colonial regions is critical for understanding the dynamics of the huge variety of normative orders in existence within the Portuguese legal regime.

To help them with their temporary overseas appointments, these judges put together travelling libraries containing the essential genres of legal literature in fashion during the late 18th century: including decisiones, repertories and practical books, deriving from the ius commune tradition, along with the new systematic compendia. The content of these libraries provides precise testimony regarding the state of legal literature in the final years of the Ancien Régime, indicating an ongoing transition towards legalism. Doctrinal books, which constituted their own authority as sources of law, had already for some time been gradually losing ground to state law.

Travelling libraries, with their reduced size and clear focus on judges’ professional needs, provided the perfect vehicle for bringing normative information to the most remote fringes of the global Portuguese empire, where this material would serve locally as the basis for judicial settlements.

Abreu, Márcia (2003), Os caminhos dos livros, São Paulo

Almeida, Jeronimo Fernandes Morgado Couceiro de (1794), Tratado orfanológico e prático, Lisboa

Amaral, Antonio Cardoso do (1610), Liber utilissimus judicibus, et advocatis, Ulysipone

Aragão, António Barnabé de Elescano Barreto (1781), Demétrio moderno ou O bibliógrafo jurídico portuguez, Lisboa

Araujo, Jerónimo da Silva de (1743), Perfectus advocatus: Tractatus de patronis, sive advocatis, theologicus, juridicus, historicus et poeticus, Ulyssipone

Barbosa, Manuel (1620), Remissiones doctorum de officiis publicis, jurisdictione, et ordine judiciario in librum primum, secundum, et tertium Ordinationum Regiarum Lusitanorum, cum concordantijs utriusque juris, legum partitarum, ordinamenti, ac novae recopilationis Hispanorum, Ulyssipone

Beck Varela, Laura (2016), The Diffusion of Law Books in Early Modern Europe: A Methodological Approach, in: Meccarelli, Massimo, María Julia Solla Sastre (eds.), Spatial and Temporal Dimensions for Legal History. Research Experiences and Itineraries (Global Perspectives on Legal History 6), Frankfurt am Main, 195–239, http://dx.doi.org/10.12946/gplh6

Beck Varela, Laura (2018), ›Memoria de los libros que son necesarios para pasar‹. Lecturas del jurista en el siglo XVI ibérico, in: CIAN–Revista de Historia de las Universidades, 21,2, 227–267, https://doi.org/10.20318/cian.2018.4476

Bellingradt, Daniel, Jeroen Salman (2017), Books and Book History in Motion: Materiality, Sociality and Spatiality, in: Bellingradt, Daniel et al. (eds.), Books in Motion in Early Modern Europe. Beyond Production, Circulation and Consumption, Cham, 1–15 |

Benton, Lauren (2002), Law and Colonial Cultures. Legal Regimes in World History, 1400–1900, Cambridge

Bethencourt, Francisco (2009), Enlightened Reform in Portugal and Brazil, in: Paquette, Gabriel (ed.), Enlightened Reform in Southern Europe and Its Atlantic Colonies, c. 1750–1830, Farnham, 41–44

Bouza, Fernando (2016), Corre manuscrito: una historia cultural de Siglo de Oro, Madrid

Cabedo, Jorge de (1602), Practicarum observationum, sive decisionum supremi senatus Regni Lusitaniae, Olyssipone

Cabral, Antonio Vanguerve (1711), Pratica judicial: muyto util e necessaria para os que principiam os officios de julgar & advogar & para todos os que solicitam causas nos auditorios de hum & outro foro, Lisboa

Cabral, Gustavo César Machado (2015), Os senhorios na América Portuguesa: o sistema de capitanias hereditárias e a prática da jurisdição senhorial (séculos XVI a XVIII), in: Jahrbuch für Geschichte Lateinamerikas 52, 65–86

Cabral, Gustavo César Machado (2017), Literatura jurídica na Idade Moderna. As decisiones no Reino de Portugal (séculos XVI e XVII), Rio de Janeiro

Cabral, Gustavo César Machado (2018), Pegas e Pernambuco: notas sobre o direito comum e o espaço colonial, in: Revista Direito e Práxis 9,2, 697–720

Camarinhas, Nuno (2009a), Bibliotecas particulares de magistrados no século XVIII, in: Oficina do Inconfidência, ano 6, n. 5, 13–32

Camarinhas, Nuno (2009b), O aparelho judicial ultramarino português. O caso do Brasil (1620–1800), in: Almanack Braziliense 9, 84–102, https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1808-8139.v0i9p84-102

Camarinhas, Nuno (2012a), As residências dos cargos de justiça letradas, in: Stumpf, Roberta, Nandini Chaturvedula (eds.), Cargos e ofícios nas Monarquias Ibéricas: Provimento, controlo e venalidade (Séc. XVII–XVIII), Lisboa, 161–172

Camarinhas, Nuno (2012b), Les magistrats et l’administration de la justice. Le Portugal et son empire colonial (XVIIe–XVIIIe siècle), Paris

Camarinhas, Nuno (2013), Justice Administration in Early Modern Portugal: Kingdom and Empire in a Bureaucratic Continuum, in: Portuguese Journal of Social Science 12,2, 179–193, https://doi.org/10.1386/pjss.12.2.179_1https://doi.org/10.1386/pjss.12.2.179_1

Camarinhas, Nuno (2018), Lugares Ultramarinos. A construção do aparelho judicial no ultramar português da época moderna, in: Análise Social 53, 136–160, https://doi.org/10.31447/as00032573.2018226.06

Castro, Gabriel Pereira da (1603), Decisiones supremi eminentissimique Senatus Portugalliae, Ulyssipone

Castro, Manuel Mendes de (1604), Repertorio das Ordenações do Reino de Portugal, Lisboa

Castro, Manuel Mendes de (1619), Practica lusitana, advocatis, judicibus, utroque foro quotidie versantibus admodum utilis, & necessária, Olysipone

Costa, Mario Julio de Almeida, Rui de Figueiredo Marcos (1999), Reforma pombalina dos estudos jurídicos, in: Boletim da Faculdade de Direito (Coimbra), vol. LXXV, 67–98

Costa, Pietro (2006), In Search of Legal Texts: Which Texts for Which Historian?, in: Michalsen, Dag (ed.), Reading Past Legal Texts, Oslo, 158–181

Cunha, Jeronymo (1743), Arte de Bachareis, ou Perfeito Juiz, na qual se descrevemos requisitos, e virtudes necessários a hum Ministro, dirigida somente aos que occupão primeiros bancos, e aos estudantes conimbricensis, Lisboa; digital copy (Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal): https://purl.pt/22273

Cunha, Mafalda Soares da, António Castro Nunes (2016), Territorialização e poder na América portuguesa. A criação de comarcas, séculos XVI–XVIII, in: Tempo 22, n. 39, 1–30, https://doi.org/10.20509/tem-1980-542x2016v223902

Danwerth, Otto (2020), The Circulation of Pragmatic Normative Literature in Spanish America (16th–17th Centuries), in: Duve, Thomas, Otto Danwerth (eds.), Knowledge of the Pragmatici. Legal and Moral Theological Literature and the Formation of Early Modern Ibero-America, Leiden, 89–130, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004425736_004

Darnton, Robert (1982), What Is the History of Books?, in: Dedalus 111, special issue “Representations and Realities”, 65–83.

Darnton, Robert (2015), Censors at Work: How States Shaped the Literature, New York

Duve, Thomas (2014), European Legal History – Concepts, Methods, Challenges, in: Duve, Thomas (ed.), Entanglements in Legal History: Conceptual Approaches (Global Perspectives on Legal History 1), Frankfurt am Main, 29–66, http://dx.doi.org/10.12946/gplh1

Duve, Thomas (2017), Global legal history. A methodological approach, in: Oxford Handbooks Online, DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935352.013.25

Duve, Thomas (2018), Legal traditions: A dialogue between comparative law and comparative legal history, in: Comparative Legal History 6:1, 15–33, https://doi.org/10.1080/2049677X.2018.1469271

Duve, Thomas (2020a), Pragmatic Normative Literature and the Production of Normative Knowledge in the Early Modern Iberian Empires (16th–17th Centuries), in: Duve, Thomas, Otto Danwerth (eds.), Knowledge of the Pragmatici. Legal and Moral Theological Literature and the Formation of Early Modern Ibero-America, Leiden, 89–130

Duve, Thomas (2020b), What is global legal history?, in: Comparative Legal History 8,2, 73–115, https://doi.org/10.1080/2049677X.2020.1830488

Febo, Belchior (1619–1625), Decisionum Senatus Regni Lvsitaniae, Olysippone

Ferreira, Manuel Lopes (1730), Prática criminal expendida na forma da praxe observada neste nosso Reino de Portugal e illustrada com muitas ordenações, leys extravagantes, regimentos e doutores, Lisboa

Fonseca, Manuel Temudo da (1643), Decisiones e Quaestiones Senatos Archiepiscopalis/Manuel Temudo da Fonseca, Ulysipone

Furtado, Júnia Ferreira (1999), Relações de poder no Tejuco: ou um teatro em três atos In Revista Tempo, Rio de Janeiro, 7, 129–142

Gama, Antonio da (1578), Decisiones supremi senatus inuictissimi Lusitaniae Regis, Vlissipone

Gomes, Alexandre Caetano (1750), Manual practico judicial, civil e criminal, Lisboa |

Hallewell, Laurence (2005), O livro no Brasil: sua história, São Paulo

Herzog, Tamar (1995), La administración como un fenómeno social: la justicia penal de la ciudad de Quito (1650–1750), Madrid

Hespanha, António Manuel (1982), História das instituições. Épocas medieval e moderna, Lisboa

Hespanha, António Manuel (1994), As Vésperas do Leviathan. Instituições e poder político: Portugal – Séc. XVII, Coimbra

Hespanha, António Manuel (2006a), O direito dos letrados no império português, Florianópolis

Hespanha, António Manuel (2006b), Porque é que existe e no que consiste um direito colonial brasileiro, in: Quaderni fiorentini per la storia del pensiero giuridico moderno 35,1, 59–82

Hespanha, António Manuel (2008), Form and Content in Early Modern Legal Books, in: Rechtsgeschichte 12, 12–50, https://doi.org/10.12946/rg12/012-050

Hespanha, António Manuel (2010a), Antigo Regime nos trópicos? Um debate sobre o modelo político do império colonial português, in: Fragoso, João, Maria de Fátima Gouvêa (eds.), Na trama das redes. Política e negócios no império português (XVI–XVIII), Rio de Janeiro, 43–93

Hespanha, António Manuel (2010b), Razões de decidir na doutrina portuguesa e brasileira do século XIX. Um ensaio de análise de conteúdo, in: Quaderni fiorentini per la storia del pensiero giuridico moderno 39, 109–151

Hespanha, António Manuel (2012), Modalidades e limites do imperialismo jurídico na colonização portuguesa, in: Quaderni fiorentini per la storia del pensiero giuridico moderno 41, 101–136

Hespanha, António Manuel (2015), Como os juristas viam o mundo, 1550–1750. Direitos, estados, pessoas, coisas, contratos, ações e crimes, Lisboa

Hespanha, António Manuel (2016), Melo Freire, Institutions of Portuguese Law, in: Dauchy, Serge et al. (eds.), The Formation and Transmission of Western Legal Culture. 150 Books that Made the Law in the Age of Printing, Cham, 307–310

Hespanha, António Manuel (2018), O modelo moderno do jurista perfeito, in: Tempo 24,1, 59–88, https://doi.org/10.1590/tem-1980-542x2018v240105

Hespanha, António Manuel (2019a), Filhos da Terra. Identidades mestiças nos confins da expansão portuguesa, Lisboa

Hespanha, António Manuel (2019b), Is There Place for a Separated Legal History? A Broad Review of Recent Developments on Legal Historiography, in: Quaderni fiorentini per la storia del pensiero giuridico moderno 48, 7–28

Leitão, António Lopes (1690), Liber utilissimus judicibus, et advocatis ad praxim de judicio finium regundorum, Conimbricae

Macedo, Antonio de Souza de (1660), Decisiones Supremi Senatus Justitiae Lusitaniae et Supremi Consilii Fisci, Ulissipone

Marques, Maria Adelaide Salvador (1963), A Real Mesa Censória e a cultura nacional. Aspectos da geografia cultural portuguesa no século XVIII, Coimbra

Martins, Maria Teresa Esteves Payan (2005), A censura literária em Portugal nos séculos XVII e XVIII, Lisboa

Moraes, Rubens Borba de (2006), Livros e bibliotecas no Brasil colonial, Brasília

Paiva, Yamê Galdino de (2017), Os regimentos dos ouvidores de comarca na América portuguesa, séculos XVII e XVIII: esboço de análise, in: Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos, https://doi.org/10.4000/nuevomundo.71578

Paquette, Gabriel (2013), Imperial Portugal in the Age of Atlantic Revolutions. The Luso-Brazilian World, c. 1770–1850, Cambridge, https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139237192

Pegas, Manuel Álvares (1669–1703), Commentaria ad Ordinationes Regni Portgugallie, Ulyssipone

Pereira, Bento (1664), Promptuarium juridicum, Ulysippone

Pona, Antonio de Paiva e (1713), Orphanologia practica, Lisboa

Ponce, Pilar, Nuno Camarinhas (2018), Justicia y letrados en la América Ibérica: administración y circulación de agentes en perspectica comparada, in: Xavier, Ângela Barreto, Federico Palomo, Roberta Stumpf (eds.), Monarquias ibéricas em perspectiva comparada (sécs. XVI–XVIII). Dinâmicas imperiais e circulação de modelos administrativos, Lisboa, 351–383

Rizzini, Carlos (1998), O livro, o jornal e a tipografia no Brasil, 1500–1822, São Paulo

Russell-Wood, A. J. R. (1998), Centros e Periferias no Mundo Luso-Brasileiro, 1500–1808, in: Revista Brasileira de História 18, n. 36, 187–250, https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-01881998000200010

Schröder, Jan (2016), Heineccius, Fundamentals of Civil Law, in: Dauchy, Serge et al. (eds.), The Formation and Transmission of Western Legal Culture. 150 Books that Made the Law in the Age of Printing, Cham, 258–261

Schwartz, Stuart (2011), Burocracia e sociedade no Brasil colonial. O Tribunal Superior da Bahia e seus Desembargadores, 1609–1751, Rio de Janeiro

Silva, Manuel Gonçalves da (1731–1740), Commentario ad ordinationes regni Portugaliae, Ulissipone

Silva, Nuno J. Espinosa Gomes da (2000), História do direito português, Lisboa

Souza, Joaquim José Caetano Pereira e (1785), Primeiras linhas sobre o processo criminal, Lisboa

Souza, José Roberto Monteiro de Campos Coelho e (1778), Remissoens das leys novíssimas, Lisboa

Souza, José Roberto Monteiro de Campos Coelho e (1783–1791), Systema, ou Collecção dos Regimentos reaes, Lisboa

Subtil, José (2010), Dicionário dos Desembargadores (1640–1834), Lisboa

Subtil, José (2011), Actores, territórios e redes de poder, entre o Antigo Regime e o liberalismo, Curitiba

Tavares, Rui (2018), O Censor Iluminado. Ensaio sobre o Pombalismo e a revolução cultural do século XVIII, Lisboa

Valasco, Álvaro (1597), Decisiones consultationum ac rerum iudicatarum in regno Lusitaniae, Spirae Nementum

Villalta, Luiz Carlos (2015), Usos do livro no mundo luso-brasileiro sob as Luzes: Reformas, censura e contestações, Belo Horizonte

Walsby, Malcolm (2013), Book Lists and Their Meaning, in: Walsby, Malcolm, Natasha Constantinidou (eds.), Documenting the Early Modern Book World. Inventories and Catalogues in Manuscript and Print, Leiden/Boston, 1–25

* This article is the result of a post-doctoral research project entitled ›The controlled circulation of normative knowledge in the Portuguese Empire‹ developed at the Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory in 2020.

1 The main source is Hespanha (2008), who also refers to these new trends in Hespanha (2019b) 14.

2 Darnton (1982) 67–69.

3 For a methodological approach combining book history and legal history, see Beck Varela (2016) 197–203.

4 Costa (2006).

5 Duve (2018) 24–25.

6 Nevertheless, the persistence of the circulation of manuscripts in the age of printing cannot be ignored. See Hespanha (2008) 15; for Spain, see Bouza (2016).

7 Hespanha (2015), § 26.

8 Bellingradt/Salman (2017).

9 Following the approach proposed by Duve (2020b). Cf. also Benton (2002).

10 Hespanha (2010a) 52–57.

11 Cabral (2015).

12 For a general description of justice administration in Brazil, see Camarinhas (2009b).

13 Subtil (2011) 35; Hespanha (2012).

14 Hespanha (1994); Cunha/Nunes (2016) 7–8.

15 This literally means ›judge from afar‹. Descriptions of the Portuguese organization of justice are based on Hespanha (2006) 361–374.

16 Cunhas/Nunes (2016) 17.

17 Camarinhas (2012a) 98.

18 Schwartz (2011).

19 Paquette (2013) 23.

20 Camarinhas (2013) 85.

21 Hespanha (2010a) 65.

22 Russell-Wood (1998) stressed this paradox: »Havia um relacionamento simbiótico entre a Coroa e a magistratura: criaturas do rei, a quem deviam suas nomeações e a autoridade a eles delegada, os magistrados enquanto uma coletividade eram fortes e consistentes sustentáculos da autoridade real. Enquanto tal, representavam os olhos e os ouvidos do rei. Era a este grupo que os reis se dirigiam no cumprimento de obrigações extra-judiciais de natureza social, econômica e administrativa, assim como nos serviços de natureza especial. Nos séculos XVII e XVIII, nenhum segmento no Brasil colonial se constituía enquanto uma classe profissional tão poderosa. Embora reforçassem a autoridade da Coroa, os desembargadores da Relação (a casa de apelação mais alta na colônia) poderiam igualmente constituir-se em uma ameaça à autoridade do vice-rei. Em um grau inferior, os ouvidores das comarcas poderiam desafiar a autoridade investida pelo rei na pessoa do governador.«

23 Hespanha (2006), see also Cabral (2018).

24 Camarinhas (2018).

25 As Duve asks (2014) 36: »can we really understand ›Europe‹ as a legal space without considering the imperial dimensions which went far beyond the borders of the continent?«

26 Bluteau’s dictionary (1728) in fact listed ›jurist‹ as one of the meanings of letrado.

27 Subrahmanyam (2019); Hespanha (2019a) 21–24.

28 For a comparative analysis of the Spanish and Portuguese administration of justice, see Ponce/Camarinhas (2018) 364–366.

29 For a recent study of métissage and the always multifaceted question of identities, see Hespanha (2019a), which, sadly, was one of his last publications.

30 Camarinhas (2012b) 122, confirms the conclusions of more general studies that noted a growing proportion of Brazilian-born magistrates over the course of the 18th century.

31 Information gathered from sources such as Subtil (2010) and the magnificent Memorial de Ministros database organized by Nuno Camarinhas, and from archives such as the Registo Geral de Mercês and the Processo de Leitura de Bacharéis, in the Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, and official correspondence available at the Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino.

32 Camarinhas (2013) 186: »To set up a new jurisdiction was always a difficult task; setting it up overseas, where the bureaucratic network was weak and with little support from other magistrates, was more difficult still. Since the mid-seventeenth century the church had established a series of advantages to complement service in the colonies: longer terms (normally six years), higher salaries and, probably the most important, a guaranteed promotion to a ›first bench‹ post, or even a place on an appeal court and the rank of desembargador, at the end of the term – in other words, access to a position for life. In this way service in the colonies offered a career short cut, as a way of skipping stages and becoming a desembargador much sooner. The Brazilian appeal courts were the main destination for these promotions, and hence it acted as a route to the top level of the judiciary«.

33 Cf. Furtado (1999).

34 In addition to the indigenous population dispersed all over the Amazonian region. Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, Conselho Ultramarino, Pará, Cx. 72.

35 Rizzini (1988) 228, 233.

36 Hallewell (2005) 72–73.

37 Moraes (2006) 4–23.

38 Bethencourt (2009).

39 Cf. Martins (2005).

40 Marques (1963).

41 Tavares (2018) 120.

42 Including that of the Roman Curia, after the reenactment of the beneplácito régio. Silva (2005) 235–236.

43 These included ordinary duties, such as examining manuscripts before printing, but also some unusual ones, such as the obligation to examine all undergraduate theses from the universities of Coimbra and Évora, and also the responsibility for selecting the manuals called »Minor Studies« to be used for teaching in schools.

44 The system of censorship outlined here underwent slight alterations in subsequent years. Nevertheless, control over the movement of books remained generally unchanged.

45 Recently, these sources have been examined to investigate the circulation of books in the Portuguese Empire, in particular between Brazil and Portugal. Nevertheless, there has been scant use of this approach in relation to legal history, since most Brazilian studies of book history have investigated literary genres such as novels and poetry, and avoided legal texts. Cf. Abreu (2003).

46 Walsby (2013) 12–13: »Most of the lists compiled in the early modern period would not have included volumes that were liable to attract the attention of the censors. The catalogue of a private library drawn up by or for its owner might purposefully exclude works considered to be heretical or too licentious by the authorities.« This is similar to authors and publishers of deliberately disruptive texts not even attempting to gain royal authorization in France, as described by Darnton (2015).

47 Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Real Mesa Censória, Cx. 155, mf. 1382. Request by Francisco de Paula Oliveira, September 20, 1817.

48 Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Real Mesa Censória, Cx. 160, maço 64.

49 Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Real Mesa Censória, Cx. 155, mf. 1382. Request by the widow Lima Viana and Sons, April 22, 1817.

50 The dispute over the manner of how to appropriately address representatives of the judiciary at the Real Audiencia of Quito provides a good illustration of the importance of ceremonies and marks of distinction; see Herzog (1995) 183–199.

51 Tavares (2018) 383.

52 Since booksellers’ lists generally provide more information, database projects like KOBINO – Circulación de libros en la Nueva España by Idalia García (UNAM) are essential for the precise identification of editions, furnishing references for other researchers who study the shipping of books overseas.

53 Walsby (2013) 18.

54 Figure 1 shows, for instance, that some entries detail the place and year of publication, but the third is referred to only as »Telemaco«, which stands for Les Aventures de Télémaque by François Fénelon, a bestseller at the time, as noted by Abreu (2003) 114.

55 Cap. XVII – Dos livros, que deve ter o juiz Cunha (1743) 103–106.

56 Cf. Hespanha (2018).

57 Cunha (1743) 103: »Ao Juiz pertence mais cuidar nesta eleição; porque como participa da vida de cigano; isto he, que não tem domicílio certo, e anda de Villa em Villa e de Cidade em Cidade por isso mesmo se deve poupar a conducções, e carretos, quanto puder […].«

58 Hespanha (2015), § 26.

59 Cunha (1743) 103: »álem [sic] de que se perdem, e damnificaõ com estas voltas; e assim quero poucos, e bons«; marginal note of section 2: »Deve eleger os melhores […].«

60 Camarinhas (2009a). I have relied significantly on this extraordinary study of magistrates’ libraries. Camarinhas, however, used postmortem inventories, while the present study is based on censorship documents. A source that contains a list of books from a given library always captures a collection at a specific point in time. Thus, while Camarinhas’ work is based on the libraries of deceased judges, usually at the end of their careers – and we cannot make assumptions as to why the deceased judge acquired and maintained each book listed during his lifetime – censorship lists capture a specific point in mid-career, allowing us to conjecture that the books were chosen precisely for use in the overseas jurisdictions to which the magistrates were relocating. Thus, their provisional, concise and professional character means that these travelling libraries can provide us with more information regarding the ratio decidendi than a stationary one.

61 In a stationary library, on the other hand, the proportion of legal books was around 52%, according to Camarinhas (2009a) 9.

62 I follow the division of genres of legal literature found in Hespanha (1982) 518–524 and Silva (2000) 362–363.

63 Barbosa (1620).

64 Pegas (1669–1703).

65 Silva (1731–1740).

66 Pona (1713).

67 Almeida (1794).

68 Cf. Cabral (2017).

69 The lists of books included Cabedo (1602), Castro (1603), Fonseca (1643), Gama (1578), Macedo (1660), Valasco (1597).

70 Febo (1619–1625).

71 Cabedo (1602), Febo (1619–1625), Gama (1578).

72 Castro (1604).

73 Hespanha (1982) 522–533. Those preferred by the judges include Amaral (1610), Leitão (1690), Pereira (1664) and Sousa (1778, 1783–1791).

74 Hespanha (2008) 31.

75 The books on forensic and notarial practice that can also be found in the magistrates’ libraries are: Cabral (1711), Castro (1619), Ferreira (1730), Sousa (1785).

76 Gomes (1750).

77 Danwerth (2020) 105.

78 Gomes (1750) ii: »Para estes escrevo e não para os que já sabem.«

79 Hespanha (2008) 28: »it disseminates basic legal learned knowledge in peripheral regions, a fact of outstanding importance in the colonial world, where the legal library of a learned European lawyer could hardly be found.«

80 Danwerth (2020) 90.

81 Araujo (1743) 83–84; Cunha (1743) 103–105. The same holds true for the ›study guides‹ analyzed by Beck Varela (2018).

82 Hespanha (2010b).

83 Aragão (1781) 128–129: »Esta obra ainda he de hum jurisconsulto do seculo decimo sexto; com tudo bem se mostra a falta de Ordem, de Methodo, e de Systema, que na compozição dela teve seu autor.«

84 Used in Coimbra after the Pombaline reforms; see Costa/Marcos (1999) 92–93.

85 Schröder (2016) 259.

86 Hespanha (2016) 311; Silva (2000) 402.

87 Collecção Chronologica dos Assentos das Casas da Supplicação e do Civel.