You wait ages for a bus, the saying goes, and then two (or three) come along at once. A similar feeling set in when Oxford University Press published two volumes on legal history in its Oxford Handbooks series within the space of four weeks last year. They are a welcome addition to the prestigious and well-established series that now boasts hundreds of volumes, including around 50 on history and over three dozen on law. The latter do not only cover established sub-disciplines of legal studies, such as jurisprudence and philosophy of law (2002), comparative law (2006, 2nd ed. 2019), international trade law (2009), the law of the sea (2015), European Union law (2015), criminal law (2014) and intellectual property (2018), but also more recent and emerging fields, including international environmental law (2007), empirical legal research (2010), behavioural economics and law (2014), international adjudication (2013), international climate change law (2016) and law and economics (3 vols., 2017). The Handbooks have become increasingly specialised with titles focusing on narrow topics such as individual national constitutions (USA, 2015; India, 2016; Canada, 2017) and important, but nevertheless discrete legal issues, for example, US health law (2017) and the sources of international law (2017). The obvious question was why, nearly two decades after the launch of the series, there was such a thing as an Oxford Handbook of American Sports Law (2018) but still no volume on the history of law. The absence of such a title was all the more striking in light of the publication of books in the series dealing with individual fields of legal history, such as the Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law (2012), the Oxford Handbook of Roman Law and Society (2016), the Oxford Handbook of Carl Schmitt (2017) and the Oxford Handbook of English Law and Literature, 1500–1700 (2017).

The gap has now been filled, one might even say crammed, with two volumes, the Oxford Handbook of European Legal History and the Oxford Handbook of Legal History, published in July and August 2018, respectively. Both were co-edited by Markus D. Dubber (Toronto), in the first instance with Heikki Pihlajamäki (Helsinki) and Mark Godfrey (Glasgow), in the second with Christopher Tomlins (Berkeley). Each Handbook runs to nearly 1200 pages and they come to a combined total of 105 chapters, six of which are co-authored. Most of the authors, some of which contributed to both volumes, are relatively senior and well-established, with many of them being true authorities on the topics they deal with.

The coverage is vast. The Oxford Handbook of Legal History, with its 57 chapters, is divided into five parts. Part I (»Contexts: Locating Legal History«) looks at the intersection of legal history with other disciplines, such as philosophy, comparative law, literature and rhetoric. Parts II and III (»Approaches: Conceptualizing Legal History« and »Perspectives: Legal History in Modern Legal Thought«) present different methodologies and perspectives, ranging from social to economic, intellectual and gendered histories, including discussions of particular key authors and certain »schools«, such as Marxism, formalism and realism. Part IV (»Traditions: Tracing Legal History«) covers a variety of legal traditions, for example, Roman law, canon law, the common law, Jewish law, Chinese law and the indigenous laws of Australia and Latin America. Part V (»Illustrations: Doing Things with Legal History«) focuses on the histories of specific areas of law, ranging from public law to European Union law, and what might be called applied legal history in adjudicatory contexts.

The 48 chapters of the Oxford Handbook of European Legal History are spread across six parts, with the first addressing historiographical and methodological approaches and the others dealing with different periods: ancient law and the early middle ages (Part II), the high and late middle ages (Part III), the early modern period in Europe and in various empires, including those extending to other parts of the world (Parts IV and V) and the modern period from the 19th century onwards (Part VI).

The aims pursued by the editors of both volumes are ambitious. They attempt nothing less than to »capture the glorious variety of research on legal history going on around the world today« |(Legal History, v) and to »update« the concept of European legal history by broadening the geographical focus to include both the common law and developments outside the European continent. Both volumes explicitly wish to adopt a broad international and comparative perspective, and one of them promises not merely to reflect the state of the discipline but also to shape it (European Legal History, v).

Given the enormous array of themes, approaches and periods covered, most reviewers would be defeated by the task of assessing whether the two volumes live up to their self-imposed goals. The two editors of this journal therefore decided to rely on the collective expertise assembled at the Max Planck Institute for European Legal History in Frankfurt. We invited all our PhD students, postdocs and senior scholars to present an overview of one or more of the book chapters at one of our monthly plenary sessions. Subsequently, 15 of them, including a sociologist, a political scientist, a philosopher and a couple of economic historians, agreed to turn their presentations into short review articles. We make them available as a dedicated Forum section in the following pages of the present volume of Rechtsgeschichte – Legal History.

Some contributors to this Forum look at clusters of articles in the Handbooks with a view to tracing overarching features of legal historiography. These include Caspar Ehlers and Zeynep Yazici Caglar, who are interested in what we actually mean when we talk about »European« and »comparative« legal history. Ehlers sets out to find common threads in the five introductory chapters to the Handbook of European Legal History (Whitman, Rückert, Lesaffer, Modéer, Duve), all of which approach the notion and the function of European legal history from different angles. Yazici Caglar undertakes a similar attempt with regard to the two articles dealing with comparative legal history, one in each of the two handbooks (Modéer, Schmidt). She adds some reflections on »doing« comparative legal history, and doing so beyond Europe, from her first-hand experience in the Frankfurt-based Max Planck Research Group »Translations and Transitions«.

Three further contributions address overarching methodological issues. Anselm Küsters, Laura Volkind and Andreas Wagner scrutinise both Handbooks for discussions of digital methods in legal history. In doing so, they apply the method of structural topic modelling. Luisa Stella de Oliveira Coutinho Silva examines how the Handbook of Legal History takes into account the findings of gender studies, feminist history and LGBTIQ legal history. Victoria Barnes, Sean Bottomley and Anselm Küsters explore the relationship between legal history and economic history. Taking the article in the Handbook of Legal History (Fleming) as a mere point of departure, they develop a broad overview of the various intersections and thus point towards fascinating further areas of research.

Other contributions to this Forum focus more strictly on specific world regions, individual periods or particular thematic areas of legal history. Mariana Dias Paes looks out for traces of African legal history across the two volumes; Christoph H.F. Meyer offers his views on each Handbook’s main article on medieval canon law (Clarke, Shoemaker); José Luis Egío García assesses the chapter on natural law in early modern legal thought (Ibbetson); Aleksi Ollikainen-Read explores the coverage of the piece on the Anglo-American law of obligations (Lobban); Peter Collin and Gerd Bender analyse the article on the law of the welfare state (Aguilera-Barchet) from the perspectives of the history of social law and employment law, respectively; Jan-Henrik Meyer engages with the chapter on the history of environmental law (Schorr).

The overall message is mixed. There is, of course, lots of praise and sheer awe of what has been achieved. By summarising the state of the art on various topics, many of the handbook chapters make important contributions to legal historiography. However, as might be expected, many of our contributors note gaps in the coverage of individual topics, frequently those that they themselves specialise in. Ehlers, for example, notes that none of the five articles mapping out the notion of European legal history mentions the pan-European phenomenon of the leges barbarorum. Reading between the lines of C.H.F. Meyer’s contribution, it appears that he would have appreciated more information on canon law in the early middle ages. Egío would have preferred more information on how natural law pervaded legal practice rather than only the writings of the great jurists. Ollikainen-Read laments the highly specific focus on discrete issues of the laws of contract and tort in a chapter that, according to its title, is supposed to cover the entire law of obligations. Bender and Collin observe that only some of the many facets of |the legal history of the welfare state have been touched upon.

Perhaps more importantly, those contributors who looked out for novel, interdisciplinary and non-Eurocentric approaches were often disappointed. Africa is not made the subject of a proper discussion as such, references to its legal history are limited and somewhat random and are mostly made through the lens of colonialism and imperialism. Discussion of digital methods throughout the two volumes is cursory and, again, somewhat arbitrary (it seems as if a planned chapter on »Legal History and Digital Humanities« was dropped). Economic issues and perspectives are hardly addressed across the various chapters; those of gender, feminism and LGBTIQ are explicitly attended to in three chapters but mostly confined to a Western outlook on gender.

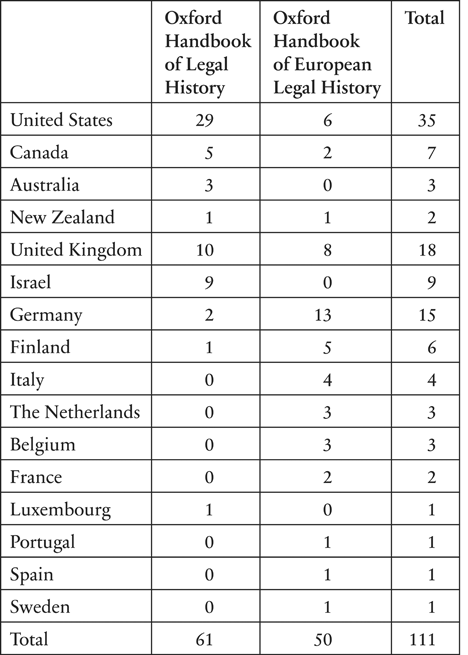

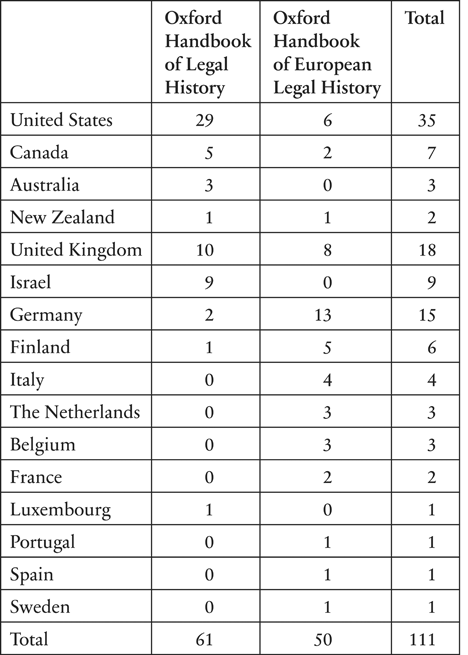

One of the overarching issues that was noted by many of our contributors and also frequently raised in the discussions in our plenary sessions is the provenance of the authors of the handbook articles. Nearly half of the 61 authors contributing to the Oxford Handbook of Legal History are based in the United States, almost a third from other English-speaking countries and 15 per cent from Israel, a jurisdiction with a thoroughly »Americanised« brand of legal scholarship. Countries that have massively contributed to legal history in the past, such as France, Italy and Spain, are not represented at all. The dominance of the Anglosphere is much less pronounced in the Oxford Handbook of European Legal History, with only a third of the authors hailing from the respective jurisdictions. Instead, there is a bias towards German and Finnish scholars, as can be seen from the following table.

Even within the countries mentioned above, the authorship is not always particularly diverse, with nearly all the Israeli authors being based at Tel Aviv and a cluster of the German contributors working in Frankfurt.

Institutional affiliation does, of course, not equate national or

regional background and expertise. Many of the Handbooks’

authors are equally at home in the legal history of their country of origin and

the history of law in one or more other countries. To make the point it suffices

to

mention the names of Duve, Reimann and Whitman. However, it is striking that two

books that set out to overcome the narrow and Eurocentric approach to legal history

do not feature a single author from Africa, Asia or Latin America or, more broadly,

the Global South. Overall, the Western World and the Global North remain the frame

of reference.

Similarly, the gender balance of the authors is far from ideal, as was already noted with some irritation in the Legal History Blog:1 while there are 21 female authors contributing to the Oxford Handbook of Legal History, the companion volume features only three female colleagues.

The present reviewer, who has some experience with editing large scale projects, is perhaps slightly more cautious in criticising the composition of the |authorial teams. All editors have to invite authors from a relatively small pool of writers that may have more members in long-established centres of research than elsewhere. The pool will also reflect the prevailing gender balance in higher education, deplorable as it may be. Finally, not all authors who are invited accept the invitation to contribute, and not all those who accept actually deliver: the stereotype of editors as grandstanding and all-powerful gatekeepers could not be further from reality. Our Forum reflects these inconvenient truths. Since all members of the Frankfurt institute were invited to write a review, our sample of 15 contributors was as self-selective as it gets. However, only five of them are female; two thirds of the contributions were written by Germans (Bender, Collin, Ehlers, Küsters, C.H.F. Meyer, J.-H. Meyer, Wagner) or members of the Institute who joined us from the UK (Barnes, Bottomley, Ollikainen-Read), the others having received their previous education in Argentina (Volkind), Brazil (Coutinho, Dias Paes), Spain (Egío) and Turkey (Yazici Caglar).

I hope that readers will enjoy the following short reviews of individual contributions from the two Oxford Handbooks. It is fair to say that no homogeneous picture of legal historical scholarship emerges from them (nor does it from my own reading of the Handbooks). The two volumes in question do not adhere to a uniform outlook, a common methodology or an overarching narrative. As such, they represent the state of play of a discipline that has become much more fragmented and multifaceted over the past three decades and that is very much in transition with regard to both the topics covered and the approaches adhered to. They therefore provide a necessarily incomplete, but broadly accurate reflection of the discipline. This is as much as one may expect from the critical reflection of the state of the art that the handbook format requires. The future of legal history will be different again, and the two magisterial volumes offer some tantalising glimpses of the direction that we are heading towards.

1 Update: Oxford Handbook of European Legal History, in: Legal History Blog, 9 October 2018, https://legalhistoryblog.blogspot.com/2018/10/update-oxford-handbook-of-european.html.