The Weimar Constitution (WRV) played a decisive role in shaping Chinese constitutions in the 1920s and 30s. The social revolution promoted by the WRV inspired translators and lawmakers alike in China to reflect on and draw the links between law and culture, as well as between translation and legislation. By means of a historical comparison of the different versions of Chinese translations of the WRV published in the early 20th century, this contribution shows how the WRV was culturally translated into the Chinese language as well as provides a theoretical framework for explaining how the WRV was adapted, reinterpreted, and recontextualized throughout several rounds of constitution-making in China. In particular, I will focus on the texts of the 1923 Constitution and the 1947 Constitution of the Republic of China (ROC).1

To begin with, I will address the dual role and responsibility of Chinese constitution translators in the 1920s and show how their translation work intersected with their political involvement. Furthermore, I will analyze the mindset of the translators and their legal knowledge. More specifically, I examine how they processed and applied implicit legal knowledge transferred from foreign countries, not to mention their inherent Chinese past, in the process of translating Weimar within the enterprise of drafting their own versions of the Chinese constitution. In the second half of this paper, drawing on the archive of the Chinese Constituent Assembly, I will demonstrate how this rights-based model (derived from the WRV) was received by Chinese lawmakers, and then I will show how it was decoded into the policy-oriented model meant to address the increasingly pressing social and economic challenges in China at that time.2 The two interpretative frameworks applied – Confucianism and the party’s doctrine – not only enable new insights into the reflective translation of Weimar, but they also shed light on our reflection on both the reception of the WRV in China as well as the constitutionalization process in modern China.

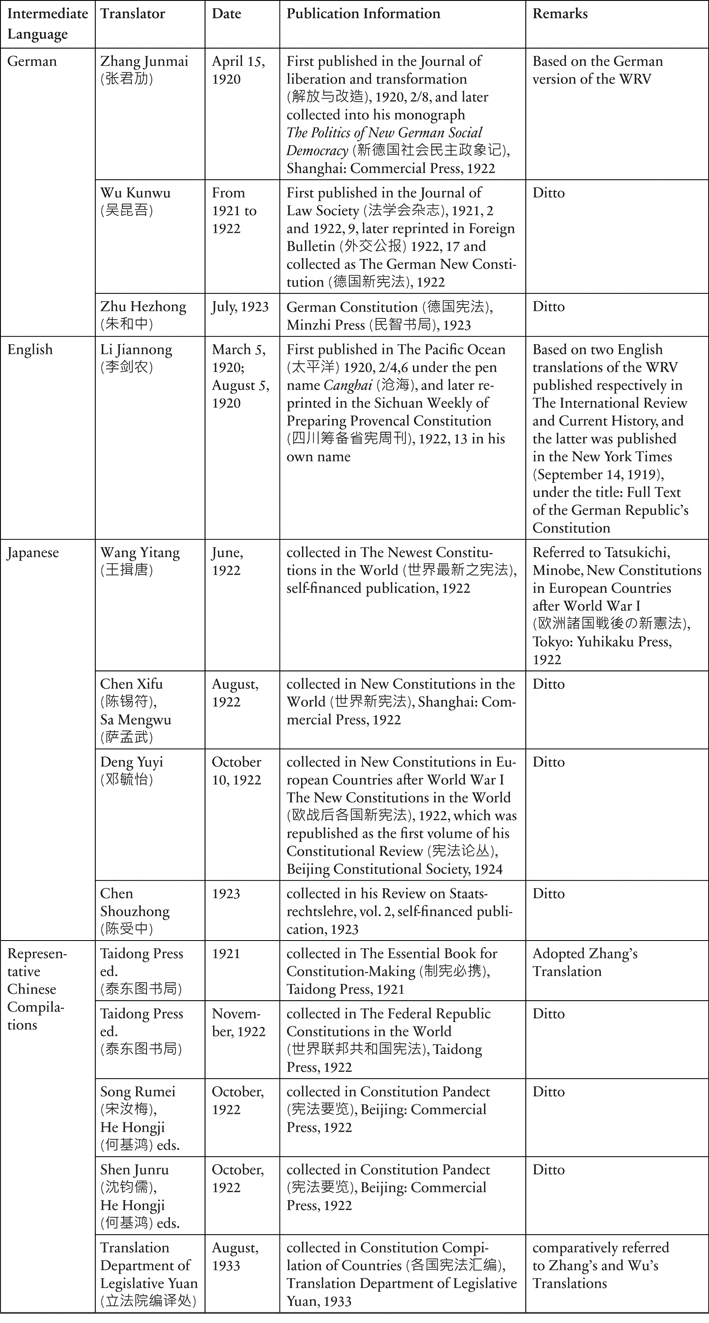

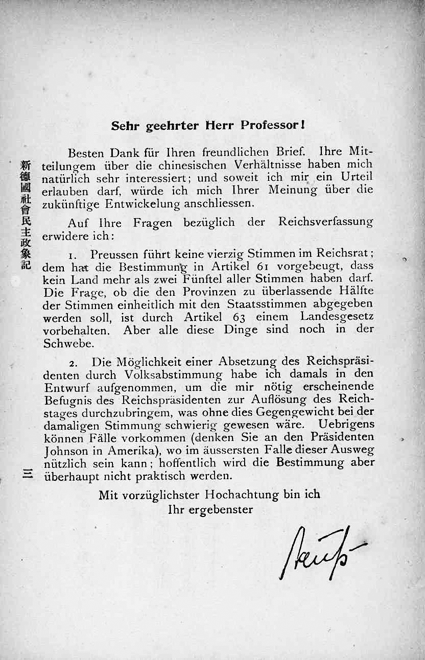

In the early 1920s, the WRV was translated into Chinese by multiple

translators. Not only did they translate from the German original but also from

the English and Japanese versions. All subsequent constitutional compilations

included the WRV, but only as a selection or reference to previous translations.

This complicated intellectual landscape of Chinese translations of the WRV could

be regarded as a consequence of translating Western legal information reaching

back to the late Qing Dynasty. However, the knowledge infrastructure completed

the transition from imperial translation agencies to overseas students, whether

government-supported or self-funded, which thus brought about the direct

appropriation from Europe and the United States rather than the over-reliance

on

Japanese understandings of the West. The detailed publication information is

listed below.3

|

The academic background of the above-mentioned translators reveals an obvious trend shifting away from the retranslation of Japanese sources to immediate and direct contact with European and American legal knowledge. Most translators went to Japan and received legal and political training there, for instance, Deng Yuyi (1903–1904, Waseda University), Wang Yitang (1904–1907, Tokyo Shinbu Gakko), Chen Shouzhong (1906–1909, Waseda University), Zhang Junmai (1906–1910, Waseda University), Li Jiannong (1910–1911, Waseda University), Sa Mengwu (1921–1923, Kyoto University), Chen Xifu (?–1924, Tokyo University). Zhang and Li, moreover, decided to continue their studies in Europe after graduation. From 1913 to 1914, Li stayed in LSE and sat in on some courses on British empiricism. Zhang, however, first went to HU Berlin for his doctoral research on Staatswissenschaft from 1913 to 1915, and in 1919 he switched to philosophy to study with Professor Rudolf Eucken in Jena. In 1920, while still studying in Germany, he translated the WRV into Chinese for the first time.

Cited by all constitutional commissions in the process of formulating China’s own constitutions, Zhang’s verisimilitude was widely cited, and his translation served as a foundational source throughout the constitution drafting process in the 1920s and 30s. Such popularity is due in part to Zhang’s direct translation from the German, which stayed very close to the original to minimize possible misinterpretations due to cross-language translations. While Li’s translation appeared at almost the exact same time, it was based on the English translation. However, all translations based on Japanese texts were published two years later, since they referenced more or less Minobe Tatsukichi’s work in 1922.4

The popularity of Zhang’s translation was further enhanced by his political engagement across China. In 1923, he was invited by the National Affairs Conference (NAC, 国是会议) in Shanghai, initiated by eight professional groups after the national assembly dissolved, to draft a constitution for the NAC, which was often cited and quoted in drafting the 1923 Constitution. After World War II, within the context of the Political Consultative Conference, Zhang made another draft of the constitution. This draft served as the basis for the 1947 constitution, which had a far-reaching impact and is still in effect today in Taiwan. Due to his substantial contribution, Zhang is revered as the founding father of the ROC Constitution. Li enjoyed a similar level of success, since he was |put forward as the Chairman of the Constitutional Committee of the Hunan Province during the United-Province Autonomy Movement ( 联省自治运动), which sought to achieve local self-government in the 1920s.

In this way, the dual roles and assumed responsibilities throughout both the translation and political movement activities show that the translation of the WRV was deeply embedded in and, in turn, contextualized by the very political climate in China in the 1920s and 30s. This process reveals the multiple dimensions of translation from the literal to the practical.5

As the first two translators of the WRV, Zhang’s and Li’s interpretations of the document reveal how Chinese legislators made sense of the WRV when they (Zhang and Li) translated Weimar into the Chinese context – a mindset that found its way into their own drafts of the Chinese constitution. Throughout their writings on the WRV, both Zhang and Li draw an analogy between the WRV and a »ferry«, that is, the legislators and »ferrymen«. In this part, I explain the two analogies in order to show how they (the two analogies) made sense of the WRV and its drafters. Furthermore, by presenting the ways in which Zhang misinterpreted – whether intentionally or unintentionally – three quotations from Hugo Preuß’ works, I will discuss how Zhang injected his own understanding as a legislator to decode Preuß’ constitutional theory. All of this provides insights into the state of mind underlying the practice of constitution-making carried out by Chinese legislators. It also provides us with the examples as to how a set of implicitly transferred and inherited knowledge from the past experience with normative order in China came alive throughout the translations of constitutions.

Zhang and Li offered two different perspectives on how to understand the status of the WRV. The first involves a comparison with the »old constitutions«, and the second observes the current social revolution from the inside.6 In other words, on the one hand, the 1918 Constitution of the Soviet Union and the 1919 WRV represent the path taken during the socialist era, and on the other, there is the inherent difference between radical and progressive reform, between the Russian and German revolutions in the concrete ways of realizing socialism. For the former, Li and Zhang place the WRV into an ever-evolving narrative via a historical perspective:

The revolutions of the 19th century were aimed at political democracy. The modern revolution is aimed at the economic and social democracy.7

From dozens of national constitutions, I think there are three of them that can represent respectively the era. That is the United States Constitution of 1789, the French Constitution of 1791, after the revolution, and the new constitution of Germany. The Constitution of the United States represents the Anglo-Saxon individualism of the 18th century, and the French Constitution represents the spirit of freedom of civil rights of the 19thcentury. The present German constitution represents the trend of the social revolution of the 20th century.8

Both Li’s dichotomy of the political and social revolution and Zhang’s three-stage historical narrative underline the remarkable representation of the WRV as the social revolution of the constitution. Moreover, Zhang’s social revolution of the constitution posits that the economic and social realities are not just complementary elements meant to enrich the content of constitutions, but that they also serve as a driving force to restructure |them. It was created in an intrinsic »revolutionary motivation«, different from previous eras.9 Zhang also quoted H.G. Wells, a novelist and historian, on the criterion for separating the new era from the old ones. »It is not political, economic or social, but rather the ways in which people make sense of humankind after the World War I.«10

For the latter perspective, when making sense of socialism, there is a major difference between the Russian and the German revolutions, between the 1918 Soviet Constitution and the 1919 WRV, if viewed from within the social revolution itself. Confronted with the choice between the »future of China, Germany or Russia«, both Zhang and Li lean toward the approach of German progressive reform, that is, a reform of the social revolution. Zhang considers German revolution to represent a »common path« for everyone to practice,11 while Li views the WRV as a »ferry« between the past and the future:

Such a constitution is like a ferry, and its role is to attempt to slowly transport Germany from the present to the future. The current Germany contains relics of feudalism and religion going back hundreds of years, as well as remnants of bureaucracy, military capital, etc. from the 19th century. Their roots go deep and are difficult to wipe out. In the future, Germany will not only achieve equality in politics but also economically, socially, and intellectually speaking, the realization of the equal status of all. Such a constitution is a medium from the present to the future. Its form is inseparable from the present, but its spirit is always focused on the future.12

The first analogy drawn between the WRV and a »ferry« is a good illustration of Li’s »instrumentality« of constitutions. On the one hand, a »ferry« is intended to carry an idea from one side to another and exhibits a transmissional and transitional nature – one capable of carrying out an incessant and gradual social revolution. On the other hand, this »ferry« moves in a clear metaphysical direction, from the present to the future, from reality to the ideal. However, he does not seek an evolutionary framework with a clear boundary between »backward« and »forward« in explaining the »present« and »future«. Quite the contrary, Zhang questions the idea that evolution would lead to perfection, and he neither believes that a political regime nor even a humanity reconfigured according to such an ideology would help us achieve such perfection. For this reason, the analogy of the ferry also highlights the instrumentality of the constitution and the uncertainty of how to employ such an instrument. As a result, Zhang stresses the importance of the legislators or »ferrymen«, according to the second analogy, who precisely navigate the ferry with their skill and experience:

The legislators are worth admiring for their outstanding mastery of techniques. As if the ferrymen skirted dangerous reefs, and the entire crew would die once the ferry hit the reef. Left or right? It is important to consider clearly before action can be taken. German political parties are not compatible with each other, and the German people also try to get to the bottom of things, always arguing over a single word. Therefore, unless there are insights into the delicate aspects of politics, as well as the excellent legislative techniques, it is not possible to complete the constitution as such. In this sense, the spirit of compromise among the German people is precious, but the wisdom of legislators has still played a key role.13

As for the WRV, the »ferry« of the era, Li was slightly optimistic: »as long as the ferryman at the helm does not get the direction and the route wrong, I believe that the ferry can reach the destination.«14 However, Zhang, who lived in Germany then and met several German politicians of various parties, saw struggles and compromises in the legislative process. According to Zhang’s observation, the German legislators merged a large number of opposing systems to reconcile the demands of the parliamentary and presidential sys|tem, the parliamentary legislation and referendum, the separation of powers and centralization, capitalism and labor, the Soviet and non-Soviet, private enterprise and socialization, respect for religion and exclusion of religion, and so on. Therefore, on the one hand, this reflects the excellent skill of legislators and, on the other, »the richness of the elasticity of the German constitution« facilitates its combination with different partisan interests and various trends of ages, creating a great deal of uncertainty. »That is why I believe that the German social revolution cannot be resolved only because of this new constitution.«15 By examining the drafting process of the WRV, Zhang realized the importance of legislators and politicians, as the guardians of the constitution in the future, since everything has yet to be set, which depends on human factors, especially the skills and wisdom of the legislators.

With regard to the WRV and the German revolution, these two analogies – ferry and ferrymen – vividly illustrate how Chinese translators made sense of this constitution. They adhered to the era of social revolution and chose a gradual approach; to this end, the WRV was selected as a reference for drafting China’s constitutions. However, Chinese translators viewed the WRV more as a tool. Its proper implementation was dependent on the legislators-ferrymen, who were to use their skill to steer this trend. As a result, it is not difficult to understand why Zhang attached such importance to the work of Hugo Preuß and introduced his theory of the state, but with a subtle misinterpretation.

In two of his works, Zhang focuses on Hugo Preuß, one of the leading drafters of the WRV. This focus is due in part to a series of tough choices they shared in common as legislators: The West or the East? Democracy or Bolshevism?16 As a result, Zhang tries to understand the choices of the WRV by interpreting Preuß’ political theory and, in turn, redefines Preuß with his own interpretation as well. Zhang’s interpretation reveals both the role expectation he assigns himself as well as the general state of mind of the Chinese legislators, which could be viewed as an implicit knowledge for drafting Chinese constitutions (from the perspective of praxeology).

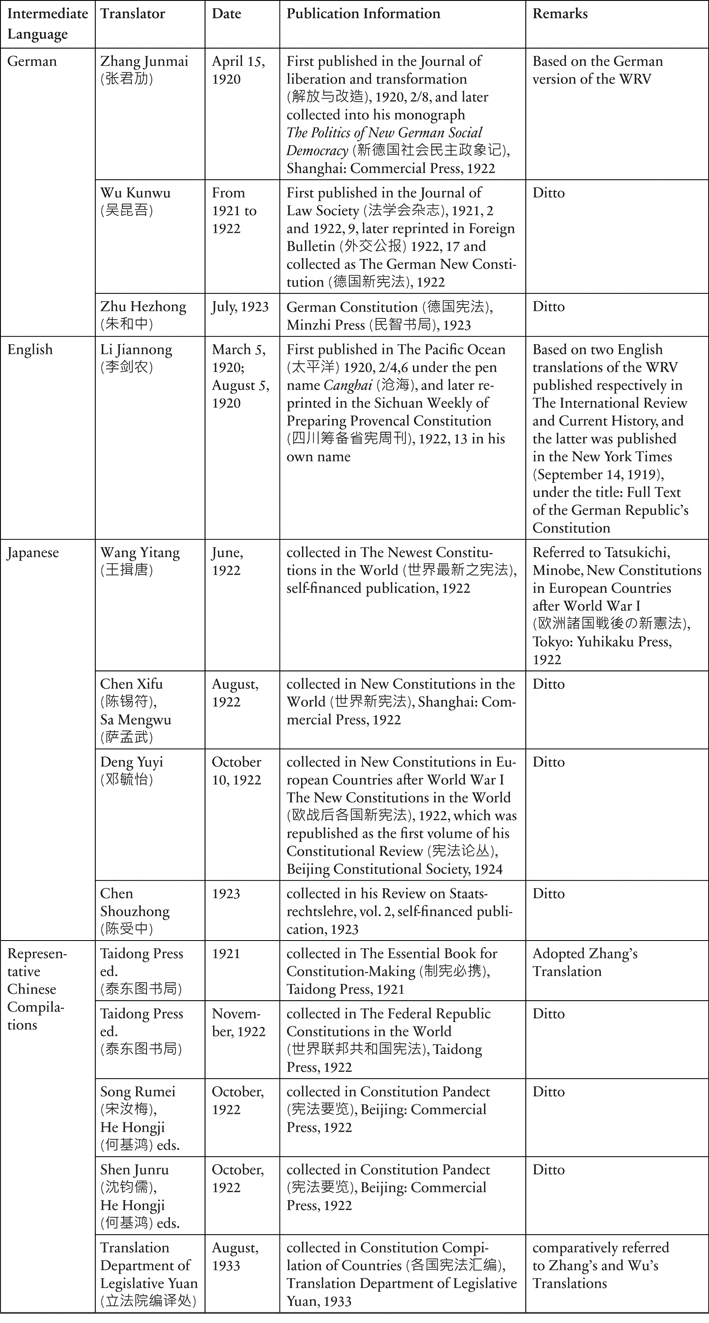

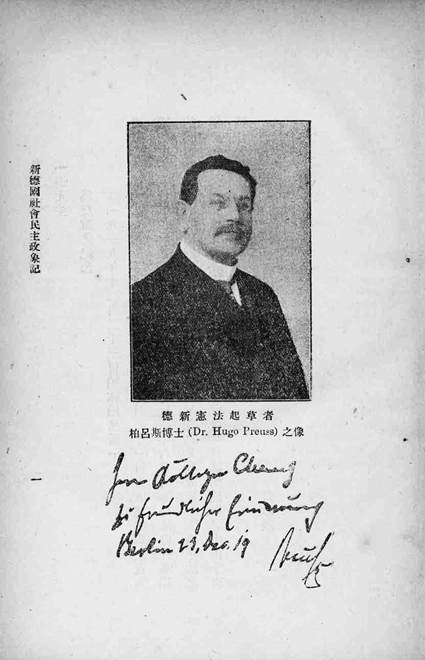

Zhang either met with or interviewed several German politicians

of various parties, such as Karl Kautsky, Rudolf Hilferding, Rudolf

Breitscheid, Eduard Bernstein, Philipp Scheidemann, etc., and these personal

contacts are helpful for accessing the details of the social revolution

beyond the surface of the grand revolutionary narrative. However, in his Comments on the WRV in 1922, Zhang expressed special

gratitude to Hugo Preuß for answering his two questions concerning the WRV,

and he even attached this reply and a photo with Preuß’ signature to the

title page. Throughout Zhang’s work, he even extols Preuß as the father of

the WRV, aligning him with his counterparts in the US and Japan.

By viewing the three quotes from Hugo Preuß’ works, observing the differences and similarities therein, we can clearly see how a concept is reproduced throughout cultural translation, from a democracy with liberal empiricism and skepticism to a »neutral« state ( 中立), and finally to the middle way ( 中道) and those literati pursuing this path, in the sense of Chinese tradition. In this regard, according to Zhang, legislators would gain a bird’s-eye view in terms of time and space, transcending people’s general basic interests to attend to the future of the country as a whole. They are not just representatives from different parties debating only with their own power and goals in mind. This creative process of translation will be discussed in detail below.

First, Zhang confirms that Preuß upholds that the state should be »neutral«; however, he never modified the Staatsform to be neutral – a term that generally expresses, according to Preuß’ work, a neutral relation between sovereignties in the sense of international law. Furthermore, for Zhang, the concept of neutrality represents a certain form of skepticism, which means that the state is not to interfere in the free competition amongst individuals or parties. Finally, he ferreted out proof from Preuß’ posthumous commentary on the WRV:

Compared to the general theories, Preuß’ point is very special. Therefore, I cannot but directly quote his original text, as follows: ›The democratic principle of political equality is not the equality of individuals, but the inability of the legal system to measure their inequality.‹ From this we can recognize that apart from the all-powerful state, there is still one unknowable state, the so-called skeptical view of the nation. Preuß further continues with the principle of free competition, ›only on this basis can the real |difference in the political value of individuals be brought to bear in the free competition of political life.‹18

This quote comes from Preuß’ posthumous work, which was edited by Gerhard Anschütz and published in 1928. In this part, fighting against the Bolshevist polemic, Preuß elucidates the »formal« principles of democracy and harshly repudiates the misinterpreted one by the Bolsheviks.19 His argument is based on the difference between three concepts: equality (Gleichheit), equivalency (Gleichwertigkeit), and the equality of rights (Gleichberechtigung).

Preuß believes the equality de jure sustaining a constitutional framework is grounded in the inequality de facto among individuals. The seemingly contradicting argument is backed up by the very fact of the gap between seeing inequality from above and experiencing inequality on the individual level. Thus, the principle of democracy manifests itself in terms of a so-called formal principle.20 However, Zhang shifts the focus from a formal framework of running democracy to a neutral position of the state. Moreover, the combination of a skeptical national view and free competition, aloofness instead of engagement – as noted by Zhang, are detrimental to the future development of a country’s political core if it remains »neutral«. Zhang’s interpretation is also interlaced with his own experiences and encounters with the political setting of the time. For example, before his third visit to Germany, Zhang was secretly arrested by KMT, the ruling political party of China. This encounter deflated his confidence in KMT. Such experiences shape is outlook and are visible throughout his interpretations of constitutional theory.21

Second, Zhang needed to answer the question as to what should serve as the pillar of the constitution in the event that the party politics is not trustworthy. In this regard, Zhang moves even further away from the neutral constitutional framework to embrace a neutral intellectual sense of fairness that goes beyond opposing parties:

In light of Preuß’ theory on this point, although he does not explicitly state it, it should be inferred from his opinions that apart from the power of political parties, there should be a neutral force. He would certainly agree with this. The meaning of neutrality in this section is different from that in the previous section. In the above, neutrality refers to the skepticism of the bystanders. This attitude is difficult to apply in current countries, where economic and social politics are turbulent. Instead, the neutrality defined here refers to those who advocate a facing of the facts and can solve problems fairly. They are not biased in favor of any party or individual. If a country does not have such a sense of neutrality, then the rule of law must not be maintained for long.22

This is not a direct quotation from Preuß, but rather an inference based on his political theory. On the one hand, Zhang explicitly acknowledges that his definition of neutrality is completely different from that of Preuß; he has transformed a seemingly passive, non-interventionist understanding into a positive commitment. In this regard, the meaning of neutrality has completely changed from non-participation to impartial judgement. On the other hand, the shift of definitions also reveals the shift of Zhang’s focus, that is, from the constitution as the operating framework of the state to certain persons who could represent intellectual fairness.

This is the third transition from state/constitution to lawmakers. Moreover, Zhang attempts to reveal the similarity between Chinese literati and the German intellectual attitude, that is, a certain independent spirit demonstrated in the third quotation (as used by Zhang) of Preuß’ evaluation of Rudolf von Gneist in his eulogy:

In today’s Germany, there are often doubts about whether there are still independent political intellectuals that reach out beyond narrow party interests […]. However, Preuß’ evaluation of Rudolf von Gneist is as follows: ›A spirit, |however, which keeps its researching gaze firmly focused on the deep inner process of gradual historical development, which dares to apply the yardstick to the political questions of the day, must put up with being celebrated today by the loud and quick-witted guardians of public opinion as the paragon of wisdom, to be fought tomorrow as apostates because of the same view.‹ Although it is much more difficult for today’s political thinkers to keep their independence than before, Preuß’ words mentioned above still ring true in the current world. Moreover, we could see Preuß’ independent spirit in his words. […] In this way, the fate of the German intellectual community and the fate of the Weimar Constitution are closely linked and never separated.23

This quote from Preuß’ memorial to Rudolf von Gneist in 1895 stresses the rapid change of public opinion: while the public, especially regarding political matters, learns very slowly, it forgets all the more quickly and loses interest in the meaning of the fundamental issue once confronted with an attractive slogan. Zhang’s emphasis, however, moves away from criticizing the public towards appreciating both Gneist’s and Preuß’ intellectual independence. Moreover, Zhang ties the fate of the WRV to the independence of the German intellectual community. In other words, Zhang not only repudiates the politics of the political parties that only serves to advance their own interests, but also the exclusion of the broad masses of people who might easily be swayed by such party politics, thus shaking the legitimacy of popular sovereignty. It means that the people should not only be represented but also guided by the sovereign. Therefore, Zhang translated the paragon of wisdom with the person of foresight ( 先觉者), in contrast with the person of hindsight or non-sight, a category also used by Sun Yat-sen in his party doctrine. I will discuss this in more detail in part three.

To sum up, through Zhang’s creative interpretation, the image of the liberal politician Hugo Preuß, as the main drafter of the WRV, gradually becomes not only the Chinese understanding of the legislator but also designates Zhang’s own role in the process. This process of concept translation includes three steps. The first step is the shift from liberal radical empiricism/skepticism to the value neutrality of the competing parties or classes. The second step is away from neutrality to a pathway ›in-between‹. This is mainly derived from the idea of Zhongyong ( 中庸), which is a central document in the Confucian tradition commonly known as the »Doctrine of the Mean«.24 When it comes to the future of China – Germany or Russia – Zhang applies the idea of Zhongyong to explain the reason for choosing the WRV: according to the sages’ words, the instructors should only teach the middle course between extremes to the people.25 Consequently, there is a third transformation from the middle way to that of guardianship, not to mention from the Chinese traditional literati to the person possessing political foresight – precisely the role as legislator Zhang envisioned for himself. This legislator is to remain neutral with respect to the different parties and transcends various party’s partial interests, and thus represents the whole of the people and guides them along the middle path.

Moreover, Zhang’s interpretation of Preuß also shows the general mindset of Chinese legislators. On the one hand, we must understand that the KMT, the Communist Party, and various democratic parties, mainly composed of intellectuals, all regard themselves as representing the fundamental interests of the overwhelming majority of the people, and not just a segment or part of them. On the other hand, one needs to keep in mind that Zhang’s concept of the person of foresight, Sun Yat-sen’s category of people’s consciousness ( 知觉), and Mao Zedong’s mass line, are all based on Wang Yangming’s theory of mind ( 阳明心学), a prominent school of Neo-Confucianism since the Ming dynasty. Therefore, this self-conception as a person of foresight not only refers to Zhang but also stands proxy for Chinese legislators as a whole. This image of the Chinese legislator implied an ambitious intention in rebuilding the relationship |between state and people that goes beyond class contradictions, not to mention a strong determination to reconfigure the constitution through the social(-ist) revolution. Therefore, they seem to be appropriating the framework consisting of social rights and duties created in the WRV. In short, the typical state of mind shared by Chinese legislators represents a certain kind of implicit knowledge (from the perspective of praxeology); this form of knowledge affects the adoption, interpretation, and recontextualization of foreign knowledge, directly or indirectly, in the process of constitution-making in modern China.

This section deals with the Chinese variants of the economic life connected with the WRV – from industry ( 实业) to livelihood ( 生计), in the Chinese traditional sense, to the national economy ( 国民经济), as it relates to fundamental national policies ( 基本国策). These expressions articulate the specific meanings, seen from the perspective of the Chinese legislators, ascribed to social-economic issues, demonstrate the changing context of the social reform, and reveal the constitutional mechanism for reconfiguring the state through policies, rather than the rights and duties used in the Weimar model.26 As a result, the Chinese constitution deftly creates a new and sustaining balance consisting of the three components belonging to the structure of the triangular constitution: sovereignty, right, and national policy. Below, I analyze two frameworks concerning how this constitutional mechanism was translated from Weimar to the Chinese context, respectively into traditional Confucianism in the 1920s and the revolutionary doctrine in the 1930s and 40s.

Constructed throughout the United-province Autonomy Movement (1920–1926), the first constitution of the ROC was announced on October 10, 1923. »Livelihood« played a central role in this constitution; as Wu notes, »the key to the whole constitute is the local system, but its spirit lies in the chapters on livelihood and education.«27 Due to the political turmoil, however, these two chapters were not submitted at the third reading and thus failed to be written into the final 1923 Constitution. Nevertheless, the draft chapter on livelihood is still worth taking seriously, since it unfolds a representative model of how to assimilate the social(-ist) normativity of the WRV within a Confucian framework, which was derived from the works of Liang Qichao ( 梁启超) and Zhang Junmai, and further developed by Lin Changmin ( 林长民), a core member of the constitutional committee. Lin continued to use the term livelihood as the chapter title and enunciated his legislative logic in the report on the draft constitution of 1923:

The articles in the chapter ›Livelihood‹ are mostly adapted from the relevant content of the Economic Life in the new constitution of Germany. In other words, the German Constitution can be perceived as the source of this chapter. However, the national livelihood has long been stressed by our classic political theory. Confucius said, ›the heads of states [or noble families] do not worry over poverty but instead over equal distribution of wealth; they do not fret over underpopulation, but whether the people are insecure. Now, if there is equality in distribution there will be no poverty; if there is harmony in society there will be no underpopulation, and if there is security, there will be subversion.‹ This is actually the fundamental idea of socialism in modern times. Moreover, Mencius focuses on the benevolent government ( 仁政), and the point is to ensure that the common people possess a steady livelihood ( 恒产), ›[Therefore the intelligent ruler will regulate the livelihood of his people] so that they have enough to support their parents and their own children […].‹ Everything just mentioned by Mencius above are the detailed rules for regulating the livelihood. According to this classic theory, we formulate the articles in the chapter ›Livelihood‹, which should not be viewed as a copy of something new from abroad.28 |

At the beginning of this report, Lin explicitly acknowledges, on the one hand, that the WRV served as the direct source of reference during the drafting of the chapter on »Livelihood« in the 1923 Constitution. On the other, he views the WRV merely as the material point of departure for the process of deconstruction – a necessary process for re-embedding key elements of the WRV into the long-accepted network of Confucian ideas such as the benevolent government ( 仁政) and people-oriented thought ( 民本). In other words, instead of the hypothesis based on class conflicts between the bourgeoisie and the working class, the legal relationship is formulated between the intelligent ruler and (all) the common people. Moreover, the link between them is the concept of the steady livelihood ( 恒产), which is always oriented towards the concrete needs of the common people in constructing a permanent order. In this regard, Art. 2 of the 1923 Constitution, concerning the distribution and usage of real estate under the supervision of the state, emanated from Art. 155 of the WRV; however, the introduction of »steady livelihood« completely changed its meaning. Then, in the last part of his report, Lin outlines a comprehensive thought on how to integrate the social(-ist) source of the WRV into the Confucian framework:

This chapter is not a chapter of the socialist constitution, but it does include the content from the socialist constitution in order to conform to the trends of the world. It aims to abolish social inequality, to provide benefits to humankind, and to avoid endless turmoils, rather than a temporary fulfillment of ordinary politics. In Yi Jing ( 易经), ›The great attribute of heaven and earth is the giving and maintaining of life. What is most precious for the sage is to get the (highest) place. What will guard this position for him? Men. How shall he collect a large population round him? By the power of his wealth.‹ The constitution of the republic is the highest position of all national people. According to the constitution, the sage could gain the people’ support through a more equitable distribution of wealth in order to guard the constitution itself. Therefore, ›the wealth is the basis [for emperors] to collect people for maintaining the position, to assure the livelihood of people, to comply with the great attribute of heaven.‹ In short, the spirit of this draft chapter does not plagiarize European new constitutions; instead, they have deeply taken root in our profound basis.29

In contrast to the Weimar model, a unified system of fundamental rights from the bottom up, Lin provides a new logic of state intergradation imposed from the top down. First, the belief in creating and maintaining life is viewed as the starting point for the construction of a Confucian order in the secular world. Second, akin to the throne in imperial China, the constitution in the Republic represents the highest position of authority in order to fulfill the livelihood of the people. Third, the constitution and the common people are channeled by traditional sages, or their contemporary counterparts, the legislators and politicians, who integrate the whole of the people within the constitution by ensuring its effective implementation. Finally, a more equitable distribution of wealth is the specific key to unite the people as a state. Therefore, the proper mechanism for integrating all the common people into the state works from the top down, namely from the transcendent worldview to the empirical political order, from the constitution to the sages/politicians and then to the common people. In short, the WRV attempts to bridge the opposing classes through the rights-based social autonomy; however, Chinese legislators highlight the difference between the so-called intelligent ruler and his people, which formulates the Chinese hypothesis on policy-oriented regulation.

In 1924, the reorganization of the Nationalist Party of China (KMT, 国民党) marked the turning point in the history of Chinese constitutional law. In response to this, Li Jiannong said, »everyone argued for the legal constituted authority ( 法统) before the reorganization, but afterwards it became the party authority ( 党统).«30 In terms of constitu|tional law, this transition meant an attempt to reconstruct the legitimacy of the state from its prior proportional representativeness to the KMT’s progressiveness in order to lead the Great National Revolution. In this sense, the chapter on »National Economy«, in both the 1936 Draft Constitution and the 1947 Constitution, was conferred a revolutionary expression. In other words, the term »national« was not a simple modifier; instead, it confirms the continuity of the KMT’s legitimacy as the party destined to carry out the transition from the national revolution to the project of nation-building and constitution-making. Therefore, the key issue faced by the KMT was how to integrate the various constitutions from around the world, above all the respective constitutions of the Weimar Republic and Soviet Union, into its framework of the Three Principles of the People: nationalism, the democracy and the people’s livelihood:

Since WWI, new constitutions have paid more attention to social regulation. Issues such as economic life and public welfare became important to the constitution […], for instance, the German Weimar Constitution and the new constitution of the Soviet Union. There is a chapter on ›National Economy‹ in this draft constitution, which is born out of the principal of people’s livelihood. According to the Fundamentals of National Reconstruction ( 建国大纲), the primary task of society lies in the people’s livelihood. In his ›Addressing Words‹, an article that appeared in the publication Min Bao ( 民报发刊词), Dr. Sun Yat-Sen ( 孙中山), as the founder of our nation, said that ›the twentieth century would be dominated by the principal of people’s livelihood.‹ […] [T]he constitution we need at present is the constitution of the Three Principles of the People, and thus the part of national economy, of course, belongs to this constitution.31

The above interpretation reveals that the 1936 Draft Constitution was geared toward the social(-ist) trend of constitutions after WWI and was deeply influenced by both the German and Soviet constitutions. On the other hand, the 1936 Draft Constitution was the achievement of the national revolution and thus should be situated within the coherent narrative of revolution, nation-building and constitution-making. In the earliest stage of consultation, the Three Principles of the People directly served as the structure for the three parts in both Wu Jingxiong’s ( 吴经熊) and Zhang Zhiben’s ( 张知本) respective private drafts. During the committee stage, Sun Ke ( 孙科), as chairman of the constitutional committee, proposed to remodel the draft based on Sun Yat-Sen’s principle of separating the sovereign power from the governance power ( 权能分离). Even more important is the category of the three subjects, with foresight, hindsight, and non-sight together serving as the hypothesis for the separation principle. In other words, only the select few capable of foresight are revolutionary leaders like Sun Yat-Sen; government officials that operate with hindsight serve the people by means of governance power; and the common people of non-sight seize the sovereign power as master of the country. Therefore, in light of the KMT’s discourse, Sun Yat-Sen, the KMT and the common people correspond to one of the above-mentioned categories constituting the three subjects, each possessing a different form of sight and consciousness. Moreover, the supreme people, those with non-sight, suggest that a mechanism other than rights serves to attain a well-balanced livelihood.

To this end, the two most significant policies are the equalization of land ownership ( 平均地权) and the restriction of private capital ( 节制资本), which are derived from the Sun Yat-Sen’s principle of the people’s livelihood and embodied in the 1936 Draft Constitution (Art. 117–123) and the 1946 Constitution (Art. 143–145). Furthermore, these two policies were written into the general principal of national economy (Art. 142) of the 1946 Constitution, i.e. »the national economy shall be based on the principle of the people’s livelihood and shall seek to effect equalization of land ownership and restriction of private capital in order to attain a well-balanced sufficiency in national wealth and people’s livelihood«. In short, the economic policy links the abstract doctrine of the KMT and concrete targets for fulfilling the livelihood of the people.

While the social-economic policies are scattered throughout several articles of the chapter on national economy in the 1936 Draft Constitution, the policy-based model takes tangible shape as a |category in the 1947 Constitution. After WWII, the Political Consultative Conference ( 政协会议) was inaugurated on January 10, 1946. Coordinated by Zhang Junmai, all of the parties – including the Nationalist (KMT) and Communist parties (CPC) – agreed upon 12 principles for amending the 1936 Draft Constitution. In accordance with Art. 11, »Fundamental National Policies should be written into the constitution, which include national defense, the foreign policy, national economy, education and culture and so on.«32 Thereafter, the Fundamental National Policies became a separate chapter in Zhang’s personal draft constitution, which is regarded as the basis for the drafting of the 1947 Constitution. During the National Constituent Assembly in November 1946, the Legislative Yuan Chair, Sun Ke, explained the meaning of the category of the fundamental national policies in his report:

Chapter 13 treats the fundamental national policies that merged from two chapters of the 1936 Draft Constitution, namely ›National Economy‹ and ›National Education‹ […]. This design lies in the notion that the national economy and education fall under the category of the fundamental policies of the state, and the national defense and the foreign policy are also the significant issues at the heart of this category. Therefore, in the draft constitution, these four fields are introduced into the chapter on ›Fundamental National Policies‹. In this chapter, several articles are particularly significant, for instance, the nationalization of the military of Art. 134 […].33

On the surface, the new category of the fundamental national policy seems to be derived from the political character of the economic and educational articles. However, the term »policy« is explicitly put forward and expanded on mainly to integrate the military and diplomatic resources into the constitution. After the war, the most significant challenge confronting the parties was the nationalization of the military. In other words, whether generalizing the term »policy« as a constitutional category or introducing other issues into this new category, such as military, diplomacy, and frontier, they are meant to generate consistency between the form, the group, the elements and resources. In contrast to the right-based model of the WRV, the 1947 Constitution completes the policy-oriented model with regards to the social-economic life. »The policies come from the party’s doctrines for realizing them. Therefore, the policy is the approach embodied in the party’s doctrine, and the party’s doctrine is the purpose of the policy.« In short, the Three Principles of the People (as the doctrine of the KMT), the fundamental national policies, and the fundamental rights and duties of the people make up a unidirectional, irreversible, and progressive structure. The policy creates a transitional mechanism between what is (the present) and what will be (the future), thus indicates the possibility of frequent social changes in a continuous social-state reconstruction.

This historical study of translating Weimar into the drafting process of the Chinese social(-ist) constitutions reveals two interdependent and interrelated phenomena of legal transfers as processes of cultural translation. The first kind of legal translation refers to the spatial transnationalization of the normative knowledge.34 For instance, Chinese legislators employed the instrument of policy in order to reconfigure the Weimar experience. This kind of translation degrades the legal paradigm to mere legal resources within the legislative comparison, which needs to be embedded into the unified framework of thinking, such as Confucianism or the party’s doctrine of the »Three People’s Principles«. This mode of national thinking, rather than the transnational references, has a more profound effect on constructing legal instruments. Moreover, we can clearly perceive the traces of national legal tradition in the process of transnational translation. In other words, there is another temporal phenomenon of legal translation in support of the coherence between legal traditions and urgent |demands at present. The sense of time leads to the historicization as well as the canonization of the existing category. Regarding »policy« as the legal instrument for regulating the social-economic life, and even broader fields, it triggers the modern transformation of Chinese meritocracy ( 贤人政治). In short, the traditional framework for conceiving the subject/citizen and its relationship to the state not only channels the complex processes of transnational legal translation, such as the adaptation, reinterpretation, and recontextualization of the foreign legal information, but it also reinforces the national legal tradition depicted in its modern form.

Beijing Library (ed.) (1990), Minguo Shiqi Zongshumu 1911–1949: Falv 民国时期总书目 1911–1949: 法律 [The National Bibliography in the Period of the Republic of China 1911–1949: Law], Beijing

Canghai 沧海 (1920), Deyizhi Xin Xianfa Pinglun 德意志新宪法评论 [Review on German New Constitution], in: Taipingyang 太平洋 [The Pacific Ocean] 2,7, 1–14

Chen, Xuanru 陈茹玄 (1947), Zengding Zhongguo Xianfashi 增订中国宪法史 [The Revised Edition of Chinese Constitutional History], Shanghai

Deng, Lilan 邓丽兰 (2008), Weimar Xianfa zai Zhongguo de Chuanbo 魏玛宪法在中国的传播 [Weimar Constitution and Transformation of the Constitutional Movement in the Republic of China 1912–1949], in: Journal of CUPL 3, 25–31

Duve, Thomas (2014), European Legal History – Concepts, Methods, Challenges, in: Duve, Thomas (ed.), Entanglements in Legal History: Conceptual Approaches (Global Perspectives on Legal History 1), Frankfurt am Main, 29–66, https://doi.org/10.12946/gplh1

Duve, Thomas (2017), Global Legal History: A Methodological Approach, in: Oxford Handbooks Online, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935352.013.25

Foljanty, Lena (2015), Legal Transfers as Processes of Cultural Translation: On the Consequences of a Metaphor, Max Planck Institute for European Legal History Research Paper Series No. 2015-09, online https://ssrn.com/abstract=2682465

Gusy, Christoph (1997), Die Weimarer Reichsverfassung, Tübingen

Gusy, Christoph (2016), Die Weimarer Verfassung zwischen Überforderung und Herausforderung, in: Der Staat. Zeitschrift für Staatslehre und Verfassungsgeschichte, deutsches und europäisches öffentliches Recht 55,3, 291–318, https://doi.org/10.3790/staa.55.3.291

Gusy, Christoph (2018), 100 Jahre Weimarer Verfassung, Tübingen

Jeans, Roger B. (1997), Democracy and Socialism in Republican China: The Politics of Zhang Junmai (Carsun Chang), 1906–1941, Lanham/MD

Legislative Yuan 立法院 (ed.) (1940), Zhonghua Minguo Xianfa Caoan Shuomingshu 中华民国宪法草案说明书 [The Interpretation to the Draft Constitution of Republic of China], Taipei

Li, Jiannong 李剑农 (1922), Deyizhi Xin Xianfa Pinglun 德意志新宪法评论 [Review on German New Constitution], in: Sichuan Choubei Shengxian Zhoukan 四川筹备省宪周刊 13, appendix, 1–46

Li, Jiannong 李剑农 (1932), Zuijin Sanshinian Zhongguo Zhengzhishi 最近三十年中国政治史 [Chinese Political History in the Last Thirty Years ], Shanghai

Lin, Changmin 林长民 (1923a), Zengjia Shengji Zhang zhi Liyou 增加生计章之理由 [The Reason for adding the Chapter of the Livelihood], in: Xianfa Huiyi Gongbao 宪法会议公报 [Constitutional Convention Bulletin] 59, 42–49

Lin, Changmin 林长民 (1923b), Shengji Zhang Tiaoxiang Shiyi 生计章条项释义 [The Interpretation to the Chapter of the Livelihood], in: Xianfa Huiyi Gongbao 宪法会议公报 [Constitutional Convention Bulletin] 59, 49–74

Minobe, Tatsukichi 美濃部達吉 (1922), Ō Shū Shokoku Sengo no Shin Kenpō 欧洲諸国戦後の新憲法 [New Constitutions in European Countries after World War I], Tokyo

National Assembly Secretariat (ed.) (1946), Guomin Dahui Shilu 国民大会实录 [The Record of National Assembly], Nanjing

Preuß, Hugo (1895/2012), Rudolf von Gneist, in: Preuß, Hugo, Gesammelte Schriften (Bd. 5, Kommunalwissenschaft und Kommunalpolitik, ed. by Christoph Müller), Tübingen, 461–465

Preuß, Hugo (1918/2008), Volksstaat oder verkehrter Obrigkeitsstaat, in: Preuß, Hugo, Gesammelte Schriften (Bd. 4, Politik und Verfassung in der Weimarer Republik, ed. by Detlef Lehnert), Tübingen, 73–75

Preuß, Hugo (1925/2008), Die Bedeutung der demokratischen Republik für den sozialen Gedanken, in: Preuß, Hugo, Gesammelte Schriften (Bd. 4, Politik und Verfassung in der Weimarer Republik, ed. by Detlef Lehnert), Tübingen, 280–291

Preuß, Hugo (1928/2015), Reich und Länder. Bruchstücke eines Kommentars zur Verfassung des Deutschen Reiches. Aus dem Nachlaß herausgegeben von Gerhard Anschütz (1928), in: Preuß, Hugo, Gesammelte Schriften (Bd. 3, Das Verfassungswerk von Weimar, ed. by Detlef Lehnert et al.), Tübingen, 299–476

Stolleis, Michael (2018), Die soziale Programmatik der Weimarer Reichsverfassung, in: Dreier, Horst, Christian Waldhoff (eds.), Das Wagnis der Demokratie: Eine Anatomie der Weimarer Reichsverfassung, München, 195–218

Tu, Weiming 杜维明 (2008), Zhongyong Dongjian 中庸洞见 [An Insight of Chung-yung], Beijing

Wu, Zongci 吴宗慈 (1988), Zhonghua Minguo Xianfashi Houbian 中华民国宪法史后编 [Supplement to Constitutional History of Republic of China], Taipei |

Zhang, Junmai 君劢 (1920a), Deguo Xingonghe Xianfa Pinglun 德国新共和宪法评论 [Review on German New Republic Constitution], in: Jiefang yu Gaizao 解放与改造 2,9, 5–24

Zhang, Junmai 君劢 (1920b), Deguo Xingonghe Xianfa Pinglun (Er Xu) 德国新共和宪法评论 (二续) [Review on German New Republic Constitution (continuation)], in: Jiefang yu Gaizao 解放与改造 2,12, 5–15

Zhang, Junmai 君劢, Zhang Dongsun 东荪 (1920), Zhongguo Zhi Qiantu: Deguo hu? Eguo hu? 中国之前途: 德国乎? 俄国乎? [The Prospect of China: Germany? Russia?], in: Jiefang yu Gaizao 解放与改造 2,14, 1–18

Zhang, Junmai 张君劢 (1922), Xin Deguo Shehui Minzhu Zhengxiang Ji 新德国社会民主政象记 [Comments on Social Democracy of New Germany], Shanghai

Zhang, Junmai 君劢 (1930), Deguo Xin Xianfa Qicaozhe Bolvsi zhi Guojia Guannian jiqi zai Deguo Zhengzhi Xueshuo shang zhi Diwei 德国新宪法起草者柏吕斯之国家观念及其在德国政治学说上之地位 [Hugo Preuß’s Idea of State and His Status in the History of German Political Theory], in: Dongfang Zazhi 东方杂志 [The Eastern Miscellany] 27,24, 69–76

1 For the methodological approach on cultural translation, see Duve (2014); Duve (2017); Foljanty (2015).

2 In this same Focus section, Xin Nie employs the term »weak rights« or »flexible rights« in analyzing the social rights in the Chinese context.

3 Beijing Library (1990) 58, 82–83, 104; Deng (2008).

4 Minobe (1922).

5 Such mediators also played an important role in the case of Argentina; see Leticia Vita’s contribution in this issue.

6 Canghai (1920) 1; Li (1922) 46. Li Jiannong wrote for the Journal of the Pacific Ocean under the pseudonym Canghai from 1920 to 1922.

7 Canghai (1920) 14; Li (1922) 61. All translations of Chinese sources into English by the author.

8 Zhang (1920a) 5; Zhang (1922) 66.

9 Zhang (1922) 382–383.

10 Zhang (1922) 395. This is not a direct quotation of Wells, but rather a translation of Zhang’s translation of Wells.

11 Zhang/Zhang (1920) 2–5.

12 Canghai (1920) 14; Li (1922) 61.

13 Zhang (1920b) 14; Zhang (1922) 119.

14 Canghai (1920) 14.

15 Zhang (1920a) 12; Zhang (1920b) 14; Zhang (1922) 105, 118–119.

16 Preuß (1918) 75.

17 Zhang (1930) 72.

18 Zhang (1930) 75. In German: »Nicht also die Gleichheit der Individuen, wohl aber die Unfähigkeit der Rechtsordnung, ihre Ungleichheit zu messen, ist das demokratische Prinzip der politischen Gleichberechtigung. Nur auf ihrer Grundlage kann sich die wirkliche Verschiedenheit des politischen Wertes der Individuen im freien Wettkampf des politischen Lebens zur Geltung bringen.« Preuß (1928) 327–328.

19 On this topic, see also Preuß (1925).

20 Preuß (1928) 326, 328.

21 Jeans (1997).

22 Zhang (1930) 76.

23 Zhang (1930) 76. In German: »Ein Geist aber, der den forschenden Blick fest auf den tief innern Prozeß der allmählichen historischen Entwicklung gerichtethält, der den so gewonnenen Maßstab auch an die politischen Tagesfragen anzulegen wagt, muß es sich gefallen lassen, von den lauten und schnellfertigen Vormündern der öffentlichen Meinung heute als Ausbund der Weisheit gefeiert, morgen wegen der gleichen Anschauung, deren innere Folgerichtigkeit sie nicht verstehen, als Abtrünniger bekämpft zu werden.« Preuß (1895) 461.

24 Tu (2008) 14.

25 Zhang/Zhang (1920) 6.

26 Stolleis (2018); Gusy (1997); Gusy (2016); Gusy (2018).

27 Wu (1988) 450.

28 Lin (1923a) 42–43.

29 Lin (1923b) 73.

30 Li (1932) 531.

31 Legislative Yuan (1940) 71.

32 Chen (1947) 255.

33 National Assembly Secretariat (1946) 399.

34 For other instances of spatial translation of Weimar, such as the South America and the common law world, see the contributions by Carlos M. Herrera and Donal Coffey in this Focus section.