»Law book« is a term with a commonly accepted definition. The Oxford English Dictionary defines »law-book« as »1. A book containing a code of laws. 2. A book treating of law«.1 Put another way, law books are books of the law: statutes, case reports, digests, practice manuals, treatises, textbooks and their accompanying reference books such as law dictionaries. They are the books that enumerate and explain the rules and procedures that govern legal systems. They are written or compiled by lawmakers (sovereigns, legislative bodies), law professors or legal practitioners (lawyers, judges, notaries).

But what is a »legal book«? Manuela Bragagnolo did not coin the term in her announcement of the 18 June 2020 workshop of the Max Planck Institute for European Legal History, »What is a Legal Book? Crossing Perspectives Between Legal History and Book History«. She explicitly hearkened to António Manuel Hespanha’s 2008 article, »Form and Content in Early Modern Legal Books«,2 and its call for »bridging the gap between material bibliography and legal history«. In her use of the term, however, Bragagnolo reached beyond the traditional boundaries of legal literature to which Hespanha confined himself and encouraged a broader definition, one that encompasses not only the perspective of the legal profession but also those of publishers and the broader public. She wrote:

Books were much more than instruments used by the ›men of law‹ at the universities and in courts. Handbooks and pragmatic books, the topics of which also included the expansive fields of moral theology and religious normativity, were also fundamental tools through which ›legal literacy‹ reached a wider audience.3

The field of legal history has begun to take greater interest in legal books as social and cultural phenomena, as objects of commerce and as artifacts. This evolving interest has paralleled my own evolution as a custodian, collector and consultant in US academic law libraries. I too have come to embrace a broader conception of legal literature, one that the term »legal book« captures more accurately than the narrower »law book«. If historians and the curators who support them are to proceed on a firm footing, Bragagnolo’s question, »What is a legal book?«, deserves an answer.

I will attempt to formulate a definition with the help of images from the books themselves. I have spent my last fifteen years at Yale collecting law books with illustrations.4 Many of these illustrations show how the legal profession, legal publishers, and critics have attempted to shape law’s public image. From these, I have selected ten in which books feature prominently as an element of the image’s iconography. They give an indication of how the books’ authors and publishers themselves regarded the book and its role in the law.

All of the images of this Rg issue’s picture series can be viewed in full color, enlarged and downloaded from the album entitled »From Law Book to Legal Book«5 in the Yale Law Library’s Flickr site.6 The album also includes dozens of related images.

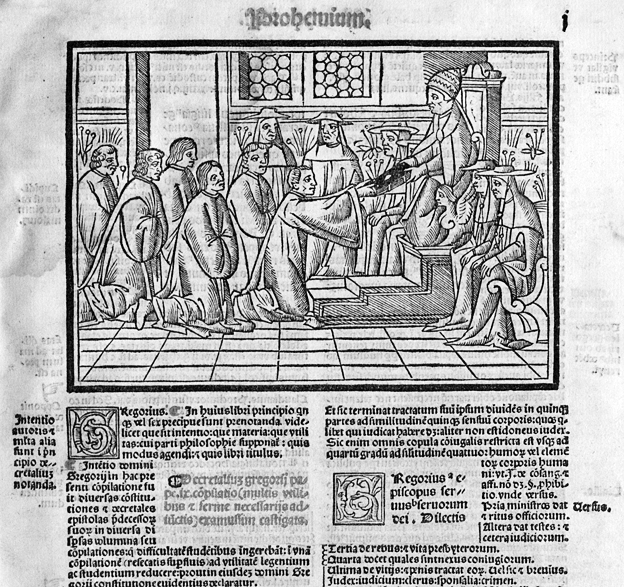

Figure 3 provides all the essential elements of a book presentation scene. It is

a detail from the opening page of the 1514 edition of the Decretals of Gregory IX, published in Venice by Luca Antonio Giunta. A kneeling Raymond of

Peñafort, the compiler of the Decretals, presents his finished work to Gregory IX, who is accompanied by his college of cardinals.

The same scene, rendered by different artists, appeared in several early 16th-century

editions of the Decretals. The 1514 Giunta Decretals is part of a three-volume set of the Corpus Juris Canonici, containing over 450 woodcuts. The set remains the most heavily illustrated work

in the history of legal literature.

Although Gregory and Raymond are the most visually prominent figures, the central element is the law book, in this case the Decretals, which passes between them. The image’s main purpose is to bestow authority on the book. It assures readers that the book carries with it the authority of both the pope and the compiler, and guarantees the text as authoritative and reliable. Authority is a central concern of litigators, judges, professors and students. The book in your hands, says the image, provides a common, trustworthy basis for all parties concerned. The parties may dispute the facts and which laws are applicable, but they can at least agree on what the law says.

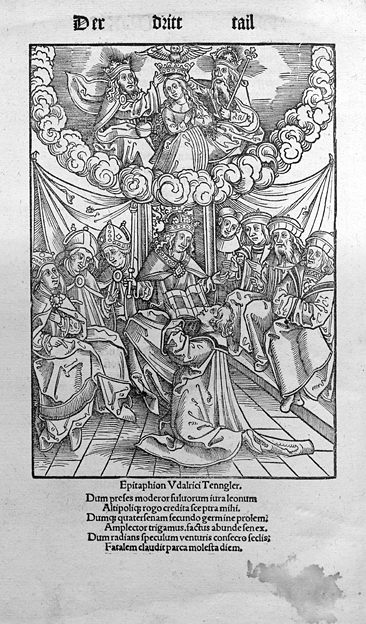

In Figure 4, from the 1514 Strassburg edition of Ulrich Tengler’s Layenspiegel,9 the cast of characters changes but the basic thrust of the image remains the same.

Here Tengler goes all out, invoking the authority of not only the emperor, but also

the Holy Trinity and the Virgin Mary, in support of his book. Both of these images

depict the »attributes of power« that Hespanha mentions, intended »to stress the authority

of their content and to promote the power of its author«.10

It must be acknowledged that discourse about a text’s authority is not necessarily the only motive for illustrations like these. Images made a book more attractive to buyers, especially those willing to pay extra. Paying homage to a patron could be another motive. The scene in the Layenspiegel suggests that Ulrich Tengler’s ego played no small part. Images of the pope, like the ones in Gregory IX’s Decretals, might have been designed to appeal to the primary market for works of canon law, namely the lawyers, bishops and other churchmen who staffed the canon law courts.

Book presentation scenes passed out of fashion before the end of the 16th century. Heavily illustrated law books, like the Giunta Decretals and Tengler’s Layenspiegel, likewise faded away, although the illustrated editions of Joost de Damhoudere’s enormously successful Praxis Rerum Criminalium, with its 50 or so woodcuts of crimes and criminal procedure, managed to go through 24 illustrated editions between 1554 and 1660. The exception was works on topics such as water law and agricultural law, where illustrations continued to help explain complex technical issues.

Here we see Justitia as the source of law’s authority, and the sovereign as merely

its custodian. In essence we are viewing an allegorical depiction of natural law,

with Justitia as the personification of nature and man’s inherent sense of justice.

Nevertheless, it is the book that remains at |the center of the transaction, as the written repository of law. A similar depiction

appears in the frontispiece to Aurora legalis, Carlo Tebaldo’s commentary on the Institutes (Figure 6),12 where Justitia delivers Tebaldo’s treatise to a doge as Justinian looks on and the

dove of the Holy Spirit hovers overhead.

The final stage in the evolution of the book presentation scene is the frontispiece

to a deluxe, folio edition of the Spanish Constitution of 1837 (Figure 7).13 Here we see the Regent María Cristina de Borbón, the self-styled »Savior of Spanish

Liberty«, presenting the book containing the Constitution to a supposedly grateful

nation, while blind Ignorance cowers and Strife flees the scene.

All these images reveal the interplay of the law book as symbol, text and artifact. The book shown in the image is a surrogate of the actual text in the accompanying pages, and a guarantee of the text’s accuracy. It also reflects the physical fact of the book as an artifact, an object that can be held in one’s hands and is accessible to at least some, if not all, of the reading public. R.J. Schoeck writes that »more than any other learned profession, […] the legal profession has clung to its visible symbols of authority, of antiquity, of respect«.14 The book is a symbol of the law, encompassing both text and artifact. It is a concrete, quotidian object, within the grasp of all. As such it is an increasingly democratic symbol, reflecting the growth of print culture and literacy. »[T]he law like every other cultural phenomenon needs physical means of expression«, writes Schoeck.15 While Justitia, with her sword and scales, is an almost universally legible icon of the law, she remains an allegory, an abstraction. Even in today’s digital universe, the law book continues to serve as a physical, tangible representation of the law.

One aspect of book presentation scenes is particularly relevant in arriving at a definition of »legal book«. These scenes are acts of communication; they show the delivery of a text. The book’s role as a communication tool is only suggested in most dictionary entries. The Oxford English Dictionary spends over 41,000 words on the etymology, definitions, and usages of »book« and its permutations, but only hints at the book’s role as a communication tool. This role did not escape Hespanha’s attention. »According to common sense, a book is only a way of conveying communicative contents«, he wrote.16 The books in these scenes are texts intended for a broader audience beyond the sovereign or the author. They perform social and cultural functions that distinguish them from private notebooks, correspondence or records of legal proceedings. By the same token, a »legal book«, for our purposes, does not necessarily take the form of a bound, printed codex. Many other physical formats can perform the same function as a codex in communicating about law to an audience. I will return to this point further on.

The author’s role in composing these illustrations should not be overlooked. The printing history of the Layenspiegel suggests that Ulrich Tengler and his son Christoph were heavily involved in commissioning and specifying the numerous illustrations that adorn the work. Additional evidence comes from an addendum to the earliest editions of Damhoudere’s Praxis rerum criminalium, where the author complained about lazy and expensive artists who failed to deliver all of the illustrations he commissioned.17 The political motives of María Cristina de Borbón are obvious.

It is especially important to note the author’s role in the allegorical frontispieces of the 17th and 18th centuries, which should not be passed over as mere window dressing. They should be seen, or rather read, as integral to the author’s text. They were often conceived, and even paid for, by the author.18 The best documented instance in law books is Cesare Beccaria’s Dei delitti e delle pene. The image of Justitia, turning away in disgust from the executioner, derives from a sketch Beccaria sent to the publisher of the third edition.19 The allegorical frontispiece of Sala’s Institutiones romano-hispanae is one of dozens in law books of the period which employ law books and law libraries in significant iconographic roles. |

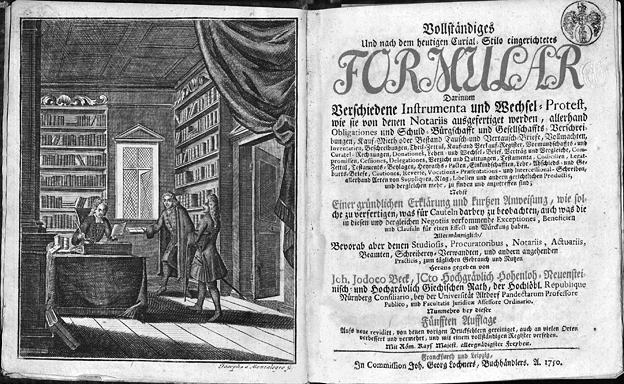

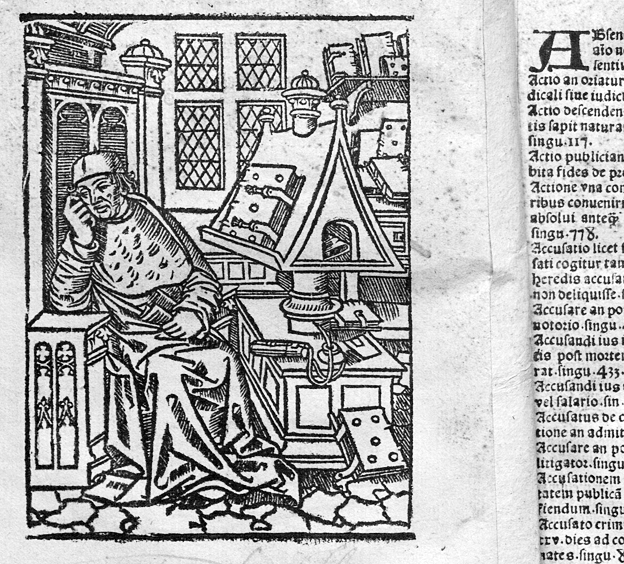

»[T]he world of law, remember, was a world based on the book«, Rodolfo Savelli reminds us.20 The next group of images portrays lawyers, law professors, judges and law students in their native habitat, books and libraries. Unlike book presentation scenes, these images are more straightforward, with limited use of allegory. Although the legal profession played a role in their creation, they were largely the work of law book publishers. They functioned in large part as a marketing tool, reflecting the legal profession’s self-image and the public image it hoped to shape. This image is of the law as a learned profession, a bookish profession, worthy of the public’s trust.

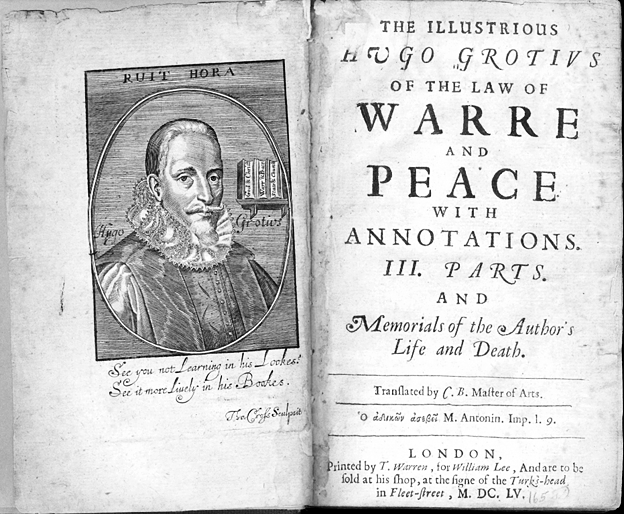

As author portraits became more common in 17th and 18th-century books, engravings replaced woodcuts as the preferred medium. Engravings allowed for much finer detail than woodcuts, but they were also more expensive, requiring the services of a skilled engraver to incise the images on metal plates, a special engraving press to transfer the image to paper, and in some cases special instructions to the bookbinder. Since many of the legal authors were dead at the time of publication, the publishers must have shouldered the costs of the engraved portraits, expecting to recoup the expense with increased sales. In other words, the portraits must have been good for sales or else the publishers would not have commissioned them.

Sperelli is portrayed as a learned and pious churchman, pausing from his writing to

gaze on the reader, with several of his published works lying close at hand, most

prominently the Decisiones fori ecclesiastici. Notably, all the titles except one are titles that Baglioni published the same year

or soon after. The portrait thus served to advertise Baglioni’s publications. A number

of other legal authors were portrayed with copies of their books, including Cornelis

van Bijnkershoek23 and Hugo Grotius (Figure 10).24 The legend below one of the Grotius portraits is particularly apt: »See you not Learning

in his Lookes. / See it more Lively in his Bookes«.

Author portraits were also common in English and Scottish law books. For at least one genre, English case reports, the portraits seem to have been used to combat a crisis of credibility. As the compiler of The Modern Reports wrote in the preface to the fifth volume, »Soon after the Martyrdom of King Charles the First, there came forth a flying Squadron of thin Reports.« These reports |had a reputation for uneven quality and dubious authorship. The same writer understood that publishers were using portraits to give the volumes a patina of reliability: »[L]et the Volumes of Law Books be as they will, the sufficiency of every Author must appear from his Works, and not from his Picture before the Title Page, or from any other Artificial Embellishment there.«25

The author portraits in English law books exhibit a marked difference from their continental counterparts: the complete absence of law books in the images. In the 52 examples from the Yale Law Library’s collection, a few of the authors are holding documents in their hands, but not a single one is pictured with a printed law book.26 For some of the authors, the images were touting their authority and reputation as judges, not as writers (which could be questionable in several cases), given that their judicial regalia received prominent display. Perhaps this difference reflects broader contrasts between the common law and the more bookish civil law; something for the comparative law folks to chew on.27

In the image of the studious, bookish lawyer, the professional aspirations of the legal profession coincided with the marketing needs of law book publishers. For the legal profession, books reinforced the perception of law as a learned profession, justifying its social status, its fees and its monopoly on law practice. For the publishers of legal texts, such images flattered their customers and encouraged them to buy more law books.

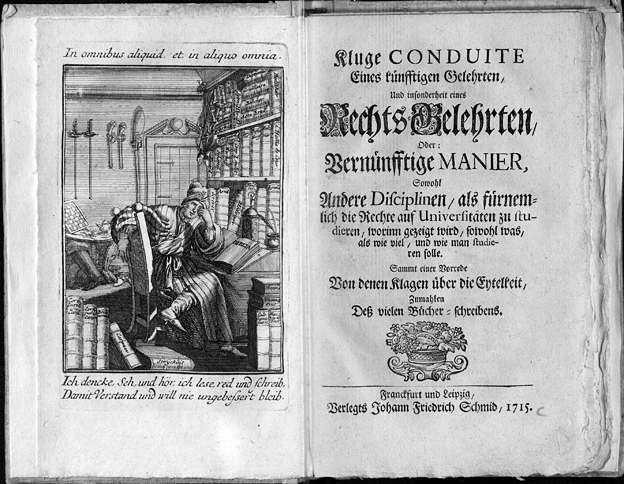

The frontispiece presents a stark contrast to the previous images. Instead of a celebration

of legal literature, we have a lamentation. The forlorn student is surrounded by enormous

piles of thick, heavy law books, whose spines provide a visual bibliography of the

legal literature of the time. There is Carpzov, Stryk, Thomasius, Böhmer, Mynsinger

and Pufendorf, to name a few. The book he has opened is the Bible, as if he is praying

for divine intervention to help him get through his studies. The image bears a striking

resemblance to one published two hundred years earlier, in a collection of the Singularia of Lodovico Pontano and other jurists (Figure 13).30

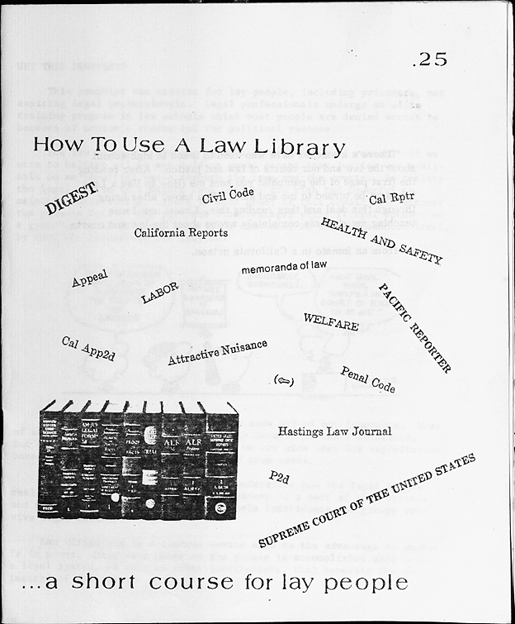

With the last two images we move beyond the traditional confines of academic law libraries

and legal history collections. After the parade of woodcuts and engravings in early

printed books shown so far, the humble 24-page brochure shown in Figure 14 might seem

out of place. Its image of law books was apparently cut out from another publication.

Its cover looks more like a ransom |note than a law book. It consists of 12 sheets of yellow bond paper folded in half

and stapled in the fold. The text was generated on a typewriter in the years before

the advent of desktop publishing. Nevertheless, How to Use a Law Library31 is a more powerful and direct testament to the power of law books than any of the

other volumes shown so far.

The Peoples Law School of San Francisco, the pamphlet’s publisher, was one of several »Peoples Law Schools« that sprang up in the early 1970s, as part of the movements to promote social and economic justice. It offered free legal education classes and pamphlets like How to Use a Law Library as antidotes to a legal system it saw as controlled by the rich and powerful. »This pamphlet was written for lay people, including prisoners, not aspiring legal professionals«, says the introduction. The nominal price of 25 cents, waived for California prison inmates, confirms the purpose:

Peoples Law School helps people understand how the legal system really operates. Unlocking the law library is part of that process, and may serve in a small way to help individuals and groups survive legal action.

It is but one of a large body of printed materials produced by social movements of both the right and left in the 20th century, with antecedents in the reform movements of early modern Europe.

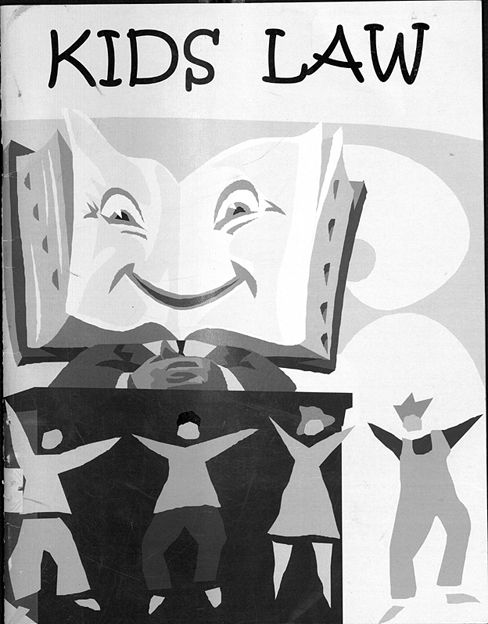

In Figure 15 we return to the iconography of the law book, in a book written for

children. Kids Law32 was prepared by the Children’s Law Office at the University of South Carolina School

of Law to explain South Carolina law to juvenile readers. The cover shows a jovial

law book personified as a judge, and indicates how the image of the law book has permeated

the public image of law and lawyers. It brings to mind the expression »throwing the

book« at someone, meaning to impose the maximum sentence on a convicted criminal.

Law and trials have long been used as motifs in moral tales for children, and as a

subject in civic education. Recent years have seen a growth in children’s books, including

coloring books, designed to explain the legal system to children in language they

can comprehend. This literature is a relatively untapped source for understanding

how popular conceptions about the legal system take shape, and how the authors attempt

to shape these conceptions. Some of the publications fill a critical need to prepare

children to deal with strange and often frightening surroundings when they are called

into court as witnesses, or sadly even as defendants.

The images of this Rg issue’s picture serieswere chosen from well over a hundred candidates. Both the images themselves and the volumes they come from suggest the contours of a definition of »legal book«. They also begin to suggest the range of materials that the term »legal book« can encompass. Apart from their legal content, they all intend to communicate legal information, to audiences both narrow and broad, both within and without the legal profession.

While the examples are all in the medium of print, manuscripts can also fall within the definition of legal book. Many legal manuscripts from the medieval and early modern eras were created to disseminate legal information to a broader audience. They were a form of small-scale publishing, with the texts duplicated by professional scribes instead of printing presses. Examples from Yale’s collection include English case reports, the glossed texts of Roman and canon law produced for the medieval law schools at Bologna and elsewhere, and Italian municipal statutes.

The examples I gave are all codices, even the simple stapled sheets of the Peoples Law School brochure in Figure 14 that most observers would not glorify with the term »book«. In my definition, however, the legal book also includes broadsides, a print genre explicitly designed for public display. Its ones I am most familiar with are the broadsides issued by northern Italian jurisdictions to publicize new laws and regulations,33 and popular accounts of notorious trials, sometimes in verse, that were common in 19th-century Britain and the United States.34 Other unusual formats include a comic book on intellectual property35 and a coloring book on secured transactions.36 |

An argument could be made for excluding fictional works from the definition of »legal book«, but I would argue the contrary. Novels such as Bleak House by Charles Dickens37 have served as potent tools for addressing legal issues, and for reflecting popular views of the law and the legal profession. Satiric verse has been another channel for critiques of the legal system, of which The Pettifoggers is one of many 18th-century examples: »Displaying the various frauds, deceits, and knavish practices, of the pettifogging counsellors, attornies, solicitors and clerks, in and about London and Westminster, and all market towns in England.«38

As stated above, my definition of »legal book« excludes manuscripts prepared for individual study, such as commonplace books, correspondence and records of legal proceedings, because they are not intended to communicate to a broad audience. I also leave aside the elephant in the room, namely digital media, in spite of its enormous presence in law today. In the task of »bridging the gap between material bibliography and legal history«, the immaterial world of digital media must necessarily be left aside for its own historians.

So, my definition for »legal book« is a text, fixed in a physical medium, intended to communicate about law to the legal profession that shapes and enforces the law, and to the broader public that law affects.

My definition of the legal book, and the illustrations I have chosen to develop the definition, have implications for historians and curators, particularly in connection with the legal book’s role as symbol, as text and as artifact.

Book presentation scenes demonstrate the role of the legal book’s parent, the law book, as a symbol of the law itself. The iconography of Justitia as she appears in legal books is further evidence. Her scales, sword and blindfold identify her, but books are quite frequently her companions. The iconography of Justitia has received considerable attention in recent years.39 The iconographic depiction of the legal book deserves similar attention by its historians. To what extent is its use a deliberate strategy on the part of publishers and authors? More broadly, how is the legal book conceived by its authors, publishers and readers? Illustrations are not the only source. Title pages, prefaces, bibliographies, publishers’ catalogues, advertisements and even bindings can tell us what historical actors included, and excluded, in their conception of the legal book.

A handful of law books have themselves achieved an iconic status. Hespanha points to the Corpora juris that became regarded as »almost sacred objects, whose physical or intellectual features were to be worshipped«,40 and to the »princely editions« that »aimed to stress the authority of their content and to promote the power of its author«.41 Such books have a role to play in legal history collections, especially those connected with law schools. The vast majority of law students are not destined to be legal historians or book historians, but the iconic books of legal literature can at least give them some understanding that they are joining a profession with an illustrious and noble past.

Studies of the typography and design of law books can illuminate their symbolic role. A recent article on the use of blackletter in English law books is a notable contribution.42 The design of law books also tells a story about early efforts to deal with information overload. The contrast between Hespanha’s »princely editions« with the utilitarian and often ugly design of modern law books is striking. Does it reflect general fashions in in book design, and in other fields such as civic architecture? What does it tell us about modern attitudes toward the law?

In considering legal books as texts and as artifacts, we come to grips with the contours of the raw material for scholarship and the collections that support that scholarship. In terms of texts, there is a general consensus about the core, namely the standard editions of statutes, codes, legal trea|tises and their related reference tools. The interesting issues, and opportunities, arise on the borders. Figures 12, 14, and 15 provide some examples. A few others will clarify the point further.

In the 19th century a number of books were published containing the US Constitution, a selection of state constitutions and miscellaneous other items such as the Declaration of Independence and George Washington’s farewell address. Most were pocket size. There is not much to differentiate one from another, apart from the titles and publishers. A researcher would not consult these for authoritative citations to constitutional law, nor would law libraries seek them out; there are much better sources. When a pair of researchers, Martha Baum and Christian Fritz, examined over a hundred different editions of these little books, they determined that these ordinary, seemingly unremarkable books were widely used as guides by delegates drafting new state constitutions, and also enjoyed a broader audience in the reading public. The authors could not have made their findings based on one or two copies, or based on normal law library collections.43

Children’s books are another example. If you would have asked knowledgeable book dealers, collectors, or librarians about collecting law-related children’s books, most of them (myself included) would have called it a fruitless task. The late Morris L. Cohen, who served as Yale’s Law Librarian from 1981 to 1991, proved us all wrong. Over the course of thirty years Cohen and his son assembled a collection of more than 200 children’s books that became the core of the Yale Law Library’s Juvenile Jurisprudence Collection, which has grown to over 300 titles. The collection provides insights into how young people form their ideas about law, and what sort of ideas the authors try to instill in the young.44

Broadsides are also worth considering. A researcher would not seek out a rare, obscure broadside to research veterinary legislation in 18th-century Bergamo, for example;45 she would consult a statutory compilation. However, the broadside illustrates the public dissemination of health regulations in ways a statutory compilation could never match. It is also an example of a legal printer’s business. Books may have enhanced a printer’s reputation, but it was broadsides and similar printed ephemera that kept a roof over his head.

Issues of scope, of inclusion and exclusion, are at the heart of collection development decisions by curators of historical law collections. The definition of a legal book determines the shape and scope of legal history collections and impacts the research agendas of historians of the legal book.

Larger libraries with long histories of collecting have already assembled relatively comprehensive core collections of statutes, codes and treatises, collections that smaller libraries will never have the resources to replicate, nor the need to do so given the large and growing corpus of online resources. For libraries large and small, opportunities for building collections with research potential are at the boundaries of the broader field of legal books. Prices for such materials are often more affordable, particularly for ephemera such as pamphlets and broadsides. New collections can also be created by simply looking at existing collections with fresh eyes. The illustrated law collection at Yale was built with both approaches. At least half of the collection was acquired decades ago for other reasons, and some of the most interesting recent acquisitions were purchased at trivial prices because they possess such limited interest for others.

Some of the best opportunities lie with more recent materials. Curators like myself have responsibilities for the historians of the future as well as those of today. Take the history of legal publishing, a topic near and dear to historians of the legal book, as an example. Several years ago my library purchased a set of 19th-century law book publishers’ ephemera sent to the G. & C. Merriam Company. I challenge anyone to find a comparable collection of the brochures and promotional materials handed out by West Publishing or Lexis/Nexis from even five or ten years ago. The vast majority ended up in hotel room waste baskets after trade shows. Familiarity breeds contempt, as the saying goes. Recent histories of legal publishers such as West show that the publishers themselves cannot be trusted to preserve their own history.46 Researchers and librarians need to confront their |biases against ephemeral materials both old and new.

Ephemera tell their own stories, but they also fill out the histories of individual volumes and genres. Collections that provide broad coverage within and between genres, both physical and intellectual, give historians and teachers the tools to tell rich, nuanced stories. The collections that curators form are data sets, designed to provide answers to existing questions and to provoke new questions, allowing researchers to mix and match, to test whether patterns emerge. In an article about Americana collector Michael Zinman, the great American rare book dealer William Reese described Zinman’s »critical mess theory« of collecting:

You don’t start off with a theory about what you’re trying to do. You don’t begin by saying, ›I’m trying to prove x.‹ You build a big pile. Once you get a big enough pile together – the critical mess – you’re able to draw conclusions about it. You see patterns.47

Although librarians operate under more constraints than Zinman, the concept is the same.

Today’s digital platforms make it increasingly easy to mix and match images of books from all over the world, and to quickly execute searches that not long ago would have been impossible. I used the Yale Law Library’s Flickr site to select the images displayed with this article. Online resources have proven especially valuable for research and teaching in a time of pandemic quarantines. Nevertheless, book historians will be among the first to insist that there is ultimately no substitute for the physical book.

This leads to my final point, the legal book as artifact. The books chosen to illustrate this article have much more to offer the book historian than their illustrations might indicate. The image from the 1514 edition of the Decretals in Figure 3 does not show expurgated passages in the glosses throughout the book. The 1714 guide for German law students (Figure 12) remains unchanged from when it left the printer’s shop, in its temporary pasteboard binding, with the pages unopened and untouched by the binder’s knife. You cannot truly appreciate the extravagance of the Spanish Constitution of 1837 in Figure 7, or the cheapness of the pamphlet in Figure 14, until you have them in front of you.

For book historians, artifactual value means evidentiary value. There is growing appreciation among curators for evidentiary value in collection development. While completeness is still important to me, I am more forgiving as regards condition. Volumes with detached boards or spines can be useful for revealing binding structures and manuscript or printer’s waste. Clean, unmarked copies were once preferred by collectors, but marginalia and inkstamps tell much richer stories about readers and the history of book ownership.

Author collections provide a useful demonstration of artifactual value. The Yale Law Library has the world’s most comprehensive collection of the works of Sir William Blackstone, author of Commentaries on the Laws of England,48 the most influential work in the history of Anglo-American law. Nothing demonstrates Blackstone’s influence like the 1,180 volumes on 160 feet/49 meters of shelves. William Sheppard (1595–1674), one of the most prolific English legal authors of the 17th century, provides another example. A bibliography shows the extent of Sheppard’s output, but when his books are lined up it becomes obvious that the majority of his works are little books. Most of Yale’s copies retain their simple, unadorned contemporary leather bindings, further evidence of their function as practical handbooks for country lawyers and lay officials, acquired for work and not for show. As objects they also reflect Sheppard the country lawyer and devout Puritan. For a study of an individual author, there is no substitute for the original books in their original states.

Historical collections of legal books are as valuable for teaching as they are for research. They can be considered as an instructional technology, one that will retain its potency and functionality long after the current iteration of smart classroom becomes obsolete. Original artifacts from the past engage a student’s interest and senses in ways that a PowerPoint slide will never approximate. The Yale Law Library’s rare book collection has hosted classes of law students, graduate students, undergraduates, secondary school students and adult |learners for both show-and-tell sessions and guided, hands-on class activities. In this aspect, collections like ours function as book museums; more like today’s interactive children’s museums than yesterday’s look-but-don’t-touch museums.

If bridges are being sought between book historians and legal historians, legal history collections can help build those bridges. The rise of digital media and the decline in institutional budgets has put increasing pressure on special collections. The intersection between legal history and book history provides new opportunities for rare book librarians like myself, and the legal collections we maintain, to demonstrate our importance for research and teaching. Let’s build some bridges with legal books.

Anonymous (1711), The Fifth and Last Part of Modern Reports, London

Anonymous (1715), Kluge conduite eines künfftigen Gelehrten, und insonderheit eines Rechts-Gelehrten, Frankfurt/Leipzig

Anonymous (1723), The Pettifoggers: A Satire, in Hudibrastick Verse, London

Anonymous (1845), Trial and Sentence of Joseph Connor for the Murder of Mary Brothers, at No. 11, George Street, St. Giles’s, on Monday, March 31st, London, https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/brittrials/10/

Aoki, Keith, Jamie Boyle, Jennifer Jenkins (2008), Bound by Law?: Tales from the Public Domain, Durham (NC), https://web.law.duke.edu/cspd/comics/digital/

Attavanti, Paolo (1479), Breviarium Totius Juris Canonici, Milan

Baloch, Tariq (2007), Law Booksellers and Printers as Agents of Unchange, in: Cambridge Law Journal 66, 385–421

Baum, Marsha L., Christian G. Fritz (2000), American Constitution-Making: The Neglected State Constitutional Sources, in: Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly 27, 199–242

Beck, Johann Jodocus (1750), Vollständiges und nach dem heutigen Curial-Stilo eingerichtetes Formular, Frankfurt/Leipzig

Bergamo, Italy (1766), Li rettori avviso, Bergamo, https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/itsta/16/

Bijnkershoek, Cornelis van (1767), Opera Omnia, Lyon

Blackstone, William (1765–1769), Commentaries on the Laws of England, 4 vols., Oxford

Bragagnolo, Manuela (2020), Workshop: Current Topic in Legal History: What is a Legal Book? Crossing Perspectives Between Legal History and Book History, https://www.rg.mpg.de/2260659/event-20-06-18-workshop-what

Children’s Law Office, University of South Carolina School of Law (2010), Kids Law: A Handbook for Children about South Carolina Law, Columbia (SC)

Cohen, Morris L. (2003), Juvenile Jurisprudence: Law in Children’s Literature, New Haven (CT)

Coke, Edward (1639), The first part of the Institutes of the lawes of England, or, A commentary upon Littleton, London

Constitución de la Monarquía Española (1837), Madrid

Constitutiones cum apparatu Joannis Andree (14th century). Manuscript on vellum. Rare Book Collection, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School

Corbett, Margery, Ronald Lightbown (1979), The Comely Frontispiece: The Emblematic Title-Page in England 1550–1660, London

Damhoudere, Joost de (1555), La practique et enchiridion des causes criminelles, Louvain

Davies, Ross E. (2011), West’s Words, Ho! Law Books by the Million, Plus a Few, in: The Green Bag, 2nd Ser., 14, 303–310

Dickens, Charles (1853), Bleak House, London

Genoa (1646), Prohibitione de coltelli, Genoa, https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/itsta/14/

Grotius, Hugo (1655), The Illustrious Hugo Grotius Of the Law of Warre and Peace, London

Hespanha, António Manuel (2008), Form and Content in Early Modern Legal Books: Bridging the Gap Between Material Bibliography and the History of Legal Thought, in: Rechtsgeschichte – Legal History 12, 12–50, http://dx.doi.org/10.12946/rg12/012-050

Niccolò de’ Tudeschi, a.k.a. Panormitanus (1477), Lectura super V libris Decretalium, vol. 1, Basel

Peoples Law School (1973), How to Use a Law Library: A Short Course for Non-lawyers, San Francisco (CA)

Pontano, Lodovico (1510), In hoc volumine continentur singularia Ludovici Romani, Paris

Resnik, Judith, Dennis Curtis (2010), Representing Justice: Invention, Controversy, and Rights in City-States and Democratic Courtrooms, New Haven (CT)

Roark, Marc L., Colin P. Marks (2017), Color Me Secured: Exploring Article 9 with Crayons, San Antonio (TX)

Sala, Juan (1788), Institutiones Romano-Hispanae, Valencia

Savelli, Rodolfo (2001), The Censoring of Law Books, in: Fragnito, Gigliola (ed.), Church, Censorship and Culture in Early Modern Italy, Cambridge (UK), 223–253

Schoeck, R. J. (1983), The Aesthetics of the Law, in: American Journal of Jurisprudence 28, 46–63

Simpson, J. A., E. S. C. Weiner (eds.) (1989), The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Oxford

Singer, Mark (2001), The Book Eater: Michael Zinman, Obsessive Bibliophile, and the Critical Mess Theory of Collecting, in: The New Yorker (5 Feb.), 62–71 |

Solon Cristobal, Kasia (2016), From Law in Blackletter to Blackletter Law, in: Law Library Journal 108, 181–216

Sperelli, Alessandro (1666), Decisiones fori ecclesiastici, Venice

Tebaldo, Carlo (1692), Aurora legalis: seu praelectiones ad quatuor libros Institutionum Iuris, Padua

Tengler, Ulrich (1514), Der neü Leyenspiegel von rechtmässigen ordnungen in burgerlichen und peinlichen Regimenten, Straßburg

Van Caenegem, Raoul C. (1987), Judges, Legislators and Professors: Chapters in European Legal History, Cambridge (UK)

Venturi, Franco (1971), Utopia and Reform in the Enlightenment, Cambridge (UK)

Widener, Michael (2012), Morris Cohen and the Art of Book Collecting, in: Law Library Journal 104, 39–43

Widener, Michael, Mark S. Weiner (2017), Law’s Picture Books: The Yale Law Library Collection, Clark (NJ)

Yale Law Library on Flickr,

https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/albums

Book presentation scenes,

https://www. flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/albums/72157717110770543

From Law Book to Legal Book,

https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/albums/72157715959547171

Law offices,

https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/albums/72157627736292996

Law libraries,

https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/albums/72157626289515082

Portraits: legal authors,

https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/albums/72157631683050307

* My thanks to Warren M. Billings, Yuksel Serindag, Fred Shapiro, Otto Vervaart, and Emma Molina Widener for their help and comments.

1 Simpson/Weiner (1989) 8, 716.

2 Hespanha (2008).

3 Bragagnolo (2020).

4 See Widener/Weiner (2017).

5 https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/albums/72157715959547171.

6 https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/.

7 Constitutiones (14th century). Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/50497427118.

8 Niccolò de' Tudeschi (1477). Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/8094768730.

9 Tengler (1514).

10 Hespanha (2008) 31.

11 Sala (1788).

12 Tebaldo (1692). Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/50866366683.

13 Constitución de la Monarquía Española (1837).

14 Schoeck (1983) 46.

15 Schoeck (1983) 48.

16 Hespanha (2008) 11.

17 Damhoudere (1555) 367.

18 Corbett/Lightbown (1979) 46.

19 Venturi (1971) 105–106.

20 Savelli (2001) 251.

21 Attavanti (1479).

22 Sperelli (1666).

23 Bijnkershoek (1767). Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/5474005691.

24 Grotius (1655). Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/4045846493.

25 Anonymous (1711), preface.

26 The only portrait containing any sort of book is the one of Sir Thomas Littleton that appears in the 1639 edition of Coke on Littleton, but the single book is obviously a Bible or devotional work since Littleton is pictured in an attitude of prayer. Coke (1639). Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/37944761276.

27 See Van Caenegem (1987).

28 Beck (1750). The book is one of a series of practitioner titles published by the Nuremberg printer and bookseller Johann Georg Lochner in the mid-18th century with depicting lawyers at work. For a sampling of images, see https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/albums/72157718137972562.

29 Anonymous (1715).

30 Pontano (1510). Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/15343095300.

31 Peoples Law School (1973).

32 Children’s Law Office (2010).

33 For example, Genoa (1646).

34 For example, Anonymous (1845).

35 Aoki (2008).

36 Roark (2017).

37 Dickens (1853).

38 Anonymous (1723).

39 For example, see Resnik (2010).

40 Hespanha (2008) 13.

41 Hespanha (2008) 31–32.

42 Solon Cristobal (2016).

43 Baum/Fritz (2000).

44 See Cohen (2003); Widener (2012).

45 Bergamo (1766).

46 Davies (2011) 303–304.

47 Singer (2001) 66.

48 Blackstone (1765–1769).