The question, what is an exchange? may prompt self-evident answers. Since the 19th century, economists as well as lawyers have characterised bourses or exchanges as the embodiment of a perfect market. They have variously been described as the »central hub of commerce«,1 the »most important […] meeting point of purchasers and traders«,2 the »brain of national economies«3 or as the »central mechanism of the capitalist system«.4 For architects, they represent a special type of trading site, while for sociologists and art photographers they show human interaction in acceleration, most famously captured in Andreas Gursky’s photograph entitled »Chicago, Board of Trade I. (1997)«. However, our memory is starting to fade: only very recently have all relevant international exchanges terminated floor trading. Trading has undergone a process of liberation from the physical constraints of the exchange hall and transformation into digital space. This brought the long history of exchanges as physical marketplaces to an abrupt end.

But when did this important institution of economic life originate? What essential features distinguished it from other trading venues? Can the Basilica Julia (54 BCE to 46 BCE), the Mercanzia in Bologna (1382) or the Lonja in Barcelona (1383) justifiably be called bourses?5 According to Fernand Braudel, bourses originated in the Mediterranean region around the 14th century, at the latest.6 More generally, dating the emergence of the byrsa, bourse, Börse, or exchange – as the English would call it after a decree of Elisabeth I7 – is all too often hindered by factual congeries of places and dates, offering little or no guidance.

This article aims to provide a history of the actual place of exchanges within Europe, from its beginning to digital dissolution in the present. The investigation takes us from 15th-century Bruges via 16th-century Antwerp and the golden age of 17th-century Amsterdam through to the present. The appearance of the world’s first exchange building was linked to the gradual emergence of international markets in the Low Countries from the late Middle Ages through to the early modern period.8 By a careful study of both the architectural design as well as the legal and economic functions of the bourse, I argue that this new type of marketplace originated in Antwerp in 1531. Exchanges beyond European borders have been in operation since the eighteenth century, as witnessed in the case of Japan.9

In the following, I show how rapid advances in trading methods and technologies were instrumental in shaping the development of exchanges throughout Europe during the past five hundred years. Three epochs may be discerned: the 16th-century Galerijbeurs or Hofhallenbörsen, the Basilica exchanges of the 19th century – the architectural designs of which came to epitomise ascendant capitalism more than any other type of building – and, finally, the closing decades of the 20th century, which witnessed the waning pre-eminence of the exchange building as physical trading site following the increased use of electronic trading and the end of parquet trading over the last ten years. |

One final caveat: the primary objective is to advance our knowledge of specific types of marketplace in history, namely, bourses or exchanges. Surprisingly enough, although financial markets, market euphoria and bubbles have always been subject to scrutiny, until now little attention has been paid to the basic question as to what impact technological, as well as legal innovations have had on the market design of this prominent institution. While the focus of this paper is on market design, the microstructure of these markets and the contract law of derivative markets, deserves a separate analysis.10

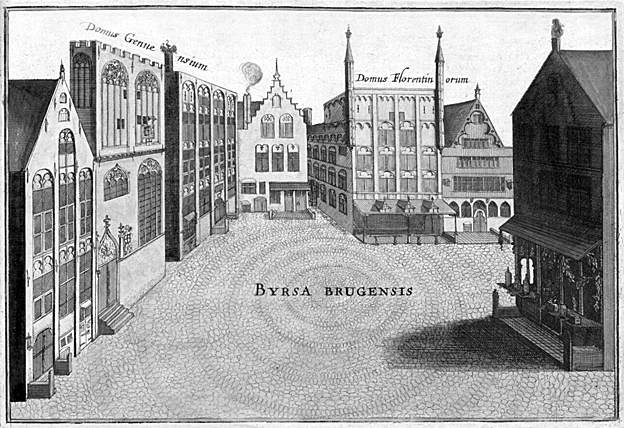

Based on the urtext on the emergence of the bourse in Europe, the account of the Italian cartographer, author and merchant Lodovico Guicciardini (1521–1589), oft-cited over the centuries,11 Bruges is commonly believed to have been the birthplace of the exchange. In travel guides, on the internet and in many popular works on economics, the building located in Vlamingstraat 35, Bruges (which can still be visited today) is called the world’s first exchange. Nevertheless, the idea of Bruges as the birthplace of the institution is ill-founded and misleading. Byrsa Brugensis was the name for an open square. No exchange building ever existed in Bruges. This is substantiated by a careful re-reading of Guicciardini’s account and by analysing the development of Bruges’ trading system since the 12th century.

In the first edition of the Descrittione di tutti i Paesi Bassi of 1567, Guicciardini describes the spread of the use of the name Borsa as follows:

Ma diciamo vn’ poco come cosa considerabile & non indegna di farne mentione, donde venga, & deriui questo nome di Borsa, tanto conuenientemente per accidente a vn’ simil’ luogo appropriato. E in Bruggia vna piazza molto commoda, a tutte le parti della terra; in testa della qual’ piazza è vna grande & antica casa, da quella nobil’ famiglia, detta della Borsa, stata edisicata, con le sue armi di viua pietra, sopra la portal, le quali armi sono tre borse. Or da questa casa, famiglia & armi, prese il nome (come comunemente in simili cose auuiene) quella piazza. Et cosi perche li mercatáti dimoranti in Bruggia, elessero, vsauano, & ancor’ hoggi per raddotto de loro negocij vsano essa piazza o, Borsa, andando eglino poi alle fiere d’ Anuersa, & di Berga, dierono anco a similitudine, & vsanza della loro di Bruggia, il nome di Borsa a quelle piazze, & luoghi, doue essi in detta Anuersa, & Berga a trafficare si raunauano.

Et d’Anuersa parimente tanto è stato fauorito & approuato questo nome, tirandolo ad altro senso, hanno poi ancora i Franzesi, portato non ha molto tempo, il medesimo nome di Borsa a Roano, & insino a Tolosa; & datolo a certe piazze, & loggie mercantili, ordinate al modo di qua, per raddotto de mercatanti […].12

But let us say, as a noteworthy and not unworthy thing to mention, from whence this name Borsa, which coincidentally is so adapted to such a place, comes and is derived. There is a square in Bruges, very comforting to all parts of the world; it starts with a large and old house built by a noble dynasty called della Borsa, with its natural stone coat of arms, which are three purses, above the door. It was from this house, lineage and coat of arms that the square took its name (as is commonly done in such a case).

And so, because the merchants who stayed in Bruges chose, used and still today use this square or bourse as their place of business, they also, when they subsequently visited the fairs of Antwerp and Bergen [op Zoom], after the similarity and the use of that in Bruges, gave the name bourse to the places and sites where they gathered to negotiate in the aforementioned Antwerp and Bergen. And in Antwerp this name has also, in a different sense, acquired so much approval and applause that later, not long ago, the French still gave the same name bourse in Rouen and Toulouse, and to certain trading places and houses, in the local manner, as the seat of merchants.13 |

By the middle of the 15th century at the latest,14 a square located in Vlamingstraat – to the north of the present-day Grand Place (Grote Markt) – was named die boers,15 de beurs,16 Byrsa Brugensis17 or Oude Burse.18 By that time, Bruges had emerged as a pivotal international market. The economic rise of the city was linked to the flood of 1134, which had opened up access to the sea from the Scheldt estuary via the Zwin.19 This paved the way for the gradual rise of the trade fairs in Bruges from 1200 onwards, the concomitant demise of those in Champagne, and the transition from (temporally limited) fair trading to a permanent market within the city.20 The square described by Guicciardini served as the meeting place of mainly Italian merchants, who specialised in exchange transactions.21

It has been claimed that this square was named after the van der Beurze family who operated three hostels, two of which were located on the Byrsa Brugensis, between the 13th and 15th centuries.22 This information is vital for clarifying the function and naming of the market place and adjacent buildings. When standing in front of the house ter Beurze in Vlamingstraat 35, in present-day Bruges, what one sees is by no means the world’s oldest bourse but rather one of three hostels erected and operated by the van de Beurze family: in other words, Ter Beurse in Vlamingstraat 35, the Ter Ouder Beurse in Vlamingstraat 37, and De Cleene Beurse, in Grauwerkersstaat 2.23 Thanks to Antonius Sanderus’ (1586–1664) pictorial reproductions in Flandria Illustrata, we have a fair idea as to the appearance of the Byrsa Brugensis square around the middle of the 17th century.

Depicted in clockwise fashion, the illustration features the trading consulate of the Genoese merchants (second building from the left, erected in 1441 (Vlamingstraat 33)), the house Ter Beurse |(third building from the left, built in 145325 (Vlamingstraat 35)), the Venetian merchants’ building (Ter Ouder Buerse, fourth building from the left, first officially documented in 128526 (Vlamingstraat 37)), and finally the trading consulate of the Florentine merchants (fifth building from the left, erected in 1429 (Academiestraat 1)). Sanderus’ illustration constitutes a snapshot. Only the Genoese are mentioned by name, since the Venetian merchants had left Bruges in favour of Antwerp at the beginning of the 16th century.27 Furthermore, by the time of Sanderus’ publication, the last person to have borne the name van de Beurze had been dead for 149 years.28 The above-mentioned house Ter Beurse in Vlamingstraat 35, erected by the van der Beurze family in the 15th century in the midst of the Italian trade consulates, operated as a hostel for about 40 years. Whether Guicciardini was referring to Ter Beurse or Ter Ouder Buerse in his Descrittione is impossible to say with absolute certainty.29

There should be no misunderstanding, however, about the kind of trading that took place on this square and within the adjacent buildings. James M. Murray30 points out that a keen interest in the origin of the exchange should not lead us to overlook the key roles played by hosteliers and brokers in the history of trading in Bruges. Indeed, though a more detailed discussion would go beyond the limits of the present article, the hosteliers, or ostelliers, were far more than mere innkeepers.31 During the period of Bruges’ economic heyday following the development of the Flemish textiles trade, when the »medieval world market«32 established itself in the town in the 14th and 15th centuries, the hostels functioned not just as guest houses but as places of hospitality and entertainment, stables, warehouses and trading centres.33 Commodities were stored in the hostel cellars (kelnare) or in nearby storage rooms.34

Regarding the significance of the institutional function of the hostel, it is important to note that it was not until well into 14th century that foreign merchants had their own building complexes in Bruges. Hostels in Bruges are not to be confused with Fondachi as we know them from the Mediterranean region, which served the merchants of their respective countries as trading places, storage space and dormitory. Such buildings did not exist in Bruges. International trade depended on the use of hostels variously located around the city and the services of the hostelier.35 The latter provided their guests with information, acted as business agents, were active in commercial transactions and payments, functioned as representatives for absent merchants, and sold the commodities stored on their premises.36 They were jointly liable for any debts accrued by their guests.37 It was not uncommon for merchants to be associated with the name of the hostel where they lodged. Thus, a merchant could be referred to as hospes Roberti de Bursa.38 Business transactions between merchants were concluded through the services of either the hostelier, a broker employed by the hostelier (makelaer or couretier), or else by an independent broker.

Furthermore, by the end of the 13th century, it was obligatory for foreign merchants to draw on the services of a broker for all transactions exceeding five Flemish pounds.39 It is commonly held that this close association between the merchants |and the hostels and hosteliers led to the custom of concluding business transactions in the hostel itself or in its immediate vicinity.40 This enabled both seller and buyer to inspect the goods on-site prior to the conclusion of the contract. Here Rudolf Häpke’s account of the daily routine of a German merchant in Bruges proves instructive:

The working day begins early each morning; it is important to make use of daylight. Buying and selling require considerable time and attention. People prefer to buy ›in person‹. Thus, the merchant himself appears at the sales hall, or even goes down into the goods cellar. One tastes, tests and touches, and perhaps even the sense of smell is exercised. One then moves on to the cumbersome task of weighing […]. The most important thing is yet to be done, negotiating a price, until, finally, the ›God's penny‹ (Gottespfennig), a small gift to charitable ends, is paid at the end of the deal, which is then celebrated by drinking wine together (Weinkauf).41

While commodity trading took place in the vicinity of the hostels and warehouses, merchants also met at various other locations throughout Bruges, among them the Byrsa Brugensis. According to Raymond de Roover, Bruges was a »money market«, the meeting place of which was the place de la Bourse. It was at this market that Italians and Spaniards would meet, though not Germans, who did not have banking facilities east of the Rhine at their disposal. According to one of de Roover’s sources dating from 1482, all merchants engaging in this activity were known as marchans de la bourse.42

To what extent does this brief digression into the economic history of Bruges advance our understanding of exchanges? In his Etymologicum Teutonicae Linguae of 1599, Cornelis Kiliaan (1528–1607), the translator of Guicciardini’s work into Dutch, describes the »exchange of the merchants«, or borse der koop-lieden as follows: »Bourse (borsa), in contemporary vernacular Bursa, derived from great house of the bursa, or purse, was the first to be thus designated in Bruges, Flanders«.43 While the designation »bourse« is not particularly original, it is certainly a fitting name for a Bruges family engaging in merchant trading as hosteliers, or for a square associated with that trade. The medieval word bursa (leather wallet or purse) can be traced back to the ancient Latin byrsa which, in turn, is based on the Greek word βύρσα (coat, skin).44 The frequent use of bursa (»purse«) as a general term for all manner of economic activity may well have led to its being employed in Bruges, too. In medieval Europe, bursa could also refer to a common fund, a commercial cooperation, or a student lodging house.45 An example of the latter use is the Bursa at Tübingen University, erected at the end of the 15th century. The rescontre, a key accounting procedure in medieval bills of exchange, was also referred to as »paying with a closed purse« (»Zahlen mit geschlossenem Beutel«).46 All this is likely to have prompted medieval merchants to call a square on which primarily currency exchanges took place »bourse«. With respect to the word bourse as designation for a place of trade, there can be little doubt that this particular name can be traced back to Bruges as an alternative to the Italian market (mercato), square (piazza) or lodge (loggia).47 In short, trading in Bruges led to the coining of the homonym by which we mean both a purse and the actual place at which trading was carried out. No more, but no less. |

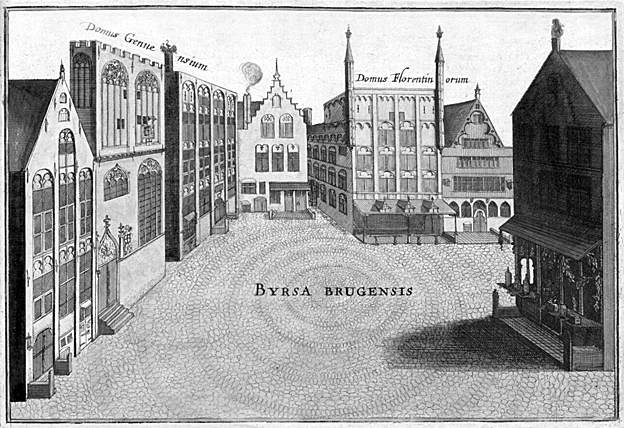

The exchange building, as a new, distinctive and independent architectonic type of economic life, became evident by 1531 at the latest, with the opening of the exchange in Antwerp.48 The Nieuwe Beurs differed from all previous trading venues in its functional design. The appearance of the world’s first exchange building has come down to us in the form of a copperplate engraving featured in Guicciardini’s aforementioned book on the Netherlands, published in 1581.

Two striking and highly significant details help characterise the building’s function. The first is that the square is »empty«: the goods are absent.53 In contrast to the Fondachi or the late Gothic trading halls of Flanders, the Antwerp bourse served as an enclosed space not for the on-site purchase or inspection of goods, but for the exchange of information and for the initiation and conclusion of contracts.54 Daily trading times were restricted and ran from 11am (later 10am) to shortly after 12 noon. Trading is also said to have taken place in the evening around 6pm.55 Merchants kept up to date about prices by reading »price currents« (cours des marchandises, Preiskuranten), printed lists of commodity prices and exchange rates.56 We have only limited knowledge of what was traded at the Antwerp bourse. Based largely on Guicciardini’s account, it is generally assumed that above all financial transactions were concluded at the Nieuwe Beurs, mainly relating to bills of exchange and insurances.57 Conversely, commodity transactions are said to have been made primarily at the so-|called Engelse beurs, the »English Exchange«,58 built a few blocks away in 1550, where trading began an hour earlier than at the Nieuwe Beurs.59

The second remarkable detail is to be found in the building’s inscription, reproduced in the lower left-hand corner of the etching: in usum negotiatorum cujuscunque nationis ac linguae (»Dedicated to the merchants of all peoples and to all languages«). The bourse became the place of general assembly for merchants of all nations: each trading nation had its place at the Bourse, where they could always be found.60 A plan of the bourse in Amsterdam shows that there, the arcades’ pillars were consecutively numbered. Each number was allocated to a type of good, vocational class or group of persons.61 Similar plans have been preserved for the Royal Exchange in London (1761) and the Neue Börse Hamburg (1841).62 Something of the lively hustle and bustle within the courtyard can be gleaned in two contemporary accounts of the Antwerp and Amsterdam bourses. A poet by the name of Daniel Rogier, cited by Richard Ehrenberg, described the atmosphere in sixteenth-century Antwerp in the following way:

What one heard was the confusing babble of all manner of languages, and what one saw was a colourful melange of all types of costume; in short, the Antwerp exchange appeared as a miniature world in which were convened all parts of the greater world.63

The German writer Filips von Zesen (1619–1689) invoked a similar picture for Amsterdam:

It is in this trading-house that virtually the whole world is negotiated. Besides German merchants from upper and lower Germany, one might find Poles, Hungarians, Walhalz, French and, indeed, occasionally even Indians, and all manner of other foreign peoples. Here, one speaks of purchasing and goods’ values, namely, the trade-off of merchant goods, loading and unloading of ships, and changing and counter-changing. Indeed, here one experiences the condition of all kingdoms and countries of the world and, no less, what is most remarkable about these.64

There has been much conjecture as to what buildings might have served as models for the Antwerp bourse. Both the Fondaco dei Turchi65 (erected in 1225) and the Fondaco dei Tedeschi66 (erected in 1228) in Venice have been suggested. |The cloister-like interior was probably also influenced by the form of Antwerp’s Oude Bourse67 a relatively small arcade in the Rue de Jardin erected in 1515.68 Furthermore, the open-roofed courtyard structure indicates that the design of the bourse of Antwerp is beholden to the concept of a marketplace.69

In contrast to the view taken here, according to which the world’s first exchange was established in Antwerp, Fernand Braudel70 cautions against the notion that the exchange is an exclusively northern European brainchild: the bourse, he argues, originated in the Mediterranean region by the 14th century, at the latest. As Braudel goes on to explain, in economic history we are familiar with merchants meeting in open-air trading places, in front of or under loggias, or in the interior of a fondaco. We know that prior to the construction of the Amsterdam exchange building in 1611, merchants would convene on the Nieuwe Brug (New Bridge) or, in bad weather, inside the Oude Kerk.71 Lombard Street in London was considered an especially prestigious location where, towards the end of the 15th century, (foreign) merchants would meet to carry out financial transactions.72 The Tontine Coffee House in New York, opened in 1793, or Café Linser in Grünangergasse, in 19th-century Vienna, seem to have served similar functions.73 In Cologne from around 1553 onwards, merchants benefited from a special license from the town council that allowed them to assemble in front of the town hall.74 Hamburg city council permitted the merchant guild »Gemeiner Kaufmann« to conduct financial transactions near the Trostbrücke in 1558.75 What confirms Antwerp’s status as the home of the first bourse of the world, however, is the concept of a building the express purpose of which was to serve as a meeting place for international merchants: the open-roofed, enclosed square. Unlike the Fondachi, the Antwerp bourse was neither a wholesale market with an attached warehouse nor an accommodation facility for merchants. The building’s function changed in so far as the goods were not »present« and that access remained unrestricted irrespective of nationality. Antwerp’s innovative forte lay in the fact that, with Charles V’s support, it was able to realise this new type of building.76 Thus, following Hunt and Murray’s assessment, there is no doubt that Antwerp, not Bruges, constitutes »the final architectural embodiment of the ›Bourse‹«.77

The events in Antwerp marked the onset of a Europe-wide process of transformation that takes us from scattered, open-air merchants’ meeting places to a centralised place of trading with no goods present in the courtyard: the exchange as we now know it. Ultimately, the architectural history of the exchange provides us with a fair idea of how, and in what spatial contexts, the exchange, as an institution evolved from 16th-century Antwerp through to the present.

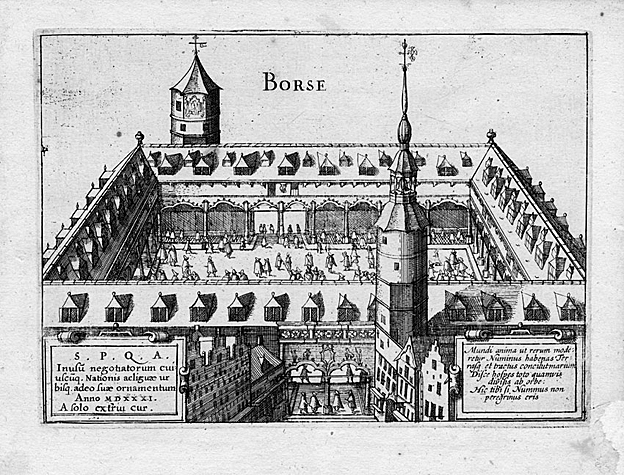

Until the 19th century, the majority of buildings housing exchanges were adaptations of the characteristic Hofhallenbörse or Galerijbeurs model |of Antwerp. Particularly worthy of mention here are the Lille Exchange (1563), the London Royal Exchange I (1566–1666) (and its successor buildings following destruction by fires the Royal Exchanges II (1669–1838) and III (1841)), the Seville Exchange (1593) and the Amsterdam Exchange (1611).78

Due to its economic and developmental significance, the Amsterdam bourse stands out as the central European market of the 17th century. The meteoric rise of Amsterdam and the Netherlands as a whole – the era known as the Golden Age of the Netherlands – was concomitant with the Dutch Uprising of 1568. The religious wars between the Catholic south and the Protestant north led to the exodus of Protestant merchants from Antwerp and their relocation north to Amsterdam, leading to Antwerp’s eventual economic decline.79 As a conveniently located shipping centre, Amsterdam established itself as Europe’s central commodities, finance and capital market. Full of admiration, Daniel Defoe writes in his book A Plan of the English Commerce (1728):

The Dutch must be understood as they really are, the Caryers of the World, the middle Person in Trade, the Factors and Brokers of Europe: that, as is said above, they buy to sell again, take in to send out: and the Greatest Part of their vast Commerce consists in being supply’d from all Parts of the World, that they may supply at the world again.80

The London Royal Exchange I also deserves brief mention. Established in 1566 by Sir Thomas |Gresham, it initially stood in the shadow of the Amsterdam market.85 That Gresham was the first to realise this project is no coincidence: having previously been in the employ of the English Crown in Antwerp as its agent in financial transactions, he was entirely familiar with the functions of the bourse. The fact that the English-speaking countries do not use the term bourse but exchange dates back to this period. We read in Guiccardini:

[I]l medesimo hanno fatto frescamente gli Inghilesi a Londra, autore & fondatore di si nobil’ machina & edifitio M. Tomaso Grassano patritio qualificatissimo di quella real’ città. Et e notabile che quando fu finito, il detto edifitio la Regina Elizabetta medesima venne a Londra per vederlo, & transferitasi sul luogo lo lodò molto, ma perche ei nó paresse copia della Borsa d’ Anuersa, gli dette il nome di Cambio reale, comandando espressamente che non si chiamasse altrimenti, nondimeno tanta forza ha hauuto quel’ nome, che non e bastato il suo comandamento a obuiare che non s’appelli comunemente Borsa.86

The same [sc. the construction of an exchange building] was recently undertaken by the English in London, under the auspices of Mr. Thomas Gresham, most honourable patrician of this royal city, namely, as author and founder of this such noble a plan and building. And it is remarkable that once the aforesaid building had been completed, Queen Elizabeth herself came to London to visit it, and at once praised it. And yet, since it did not appear to be a copy of the Antwerp Bourse, awarded it the name Royal Exchange, expressly declaring thereby, that it ought not to be called otherwise. Nevertheless, this name commanded such great power that her command was insufficient to prevent it from being commonly called Borsa.87

Guiccardini’s account is corroborated by John Stow’s own version of the incident in his A Summarie of the Chronicles of England (1574), according to which Elizabeth I (1533–1603), following a meal with Sir Thomas Gresham, »caused the same Burse by an Harolt of Armes and sounde of Trompet to be proclaymed The Royal Exchange, so to be called from thence forth and not otherwayes«.88 Whether, as Guiccardini insinuates, vanity played a role in this attempt to dissociate it from the Antwerp bourse, need not concern us here.

The early history of the Royal Exchange similarly provides a rich source material for the phenomenon of local fixation and the impact of selective regulatory procedure in speculative trading. Whereas, until the end of the 17th century the Royal Exchange was still regarded as London’s central trading place,89 speculative trading in shares and government bonds later gradually shifted to the famous coffeehouses in Exchange Alley.90 As an early first act of market regulation, a law was passed in 1696 »to restrain the number and the ill practice of Brokers and Stockjobbers«.91 With the introduction of this statute, trading was restricted to one hundred licensed brokers and stringent trading rules were introduced. There can be no question as to the failure of this regulatory measure, since the majority of brokers operating at the Royal Exchange left in 1698, which led to an unprecedented increase in trading at the coffeehouses.92 It was in these coffeehouses that the renewed endeavour to establish an exclusive club of brokers was undertaken. This, in turn, led to the foundation of the London Stock Exchange in 1773, prior to relocation to a trading room in Capel Court in 1801.93 Thus, trading once again shifted from the coffeehouses back to an exchange building. |

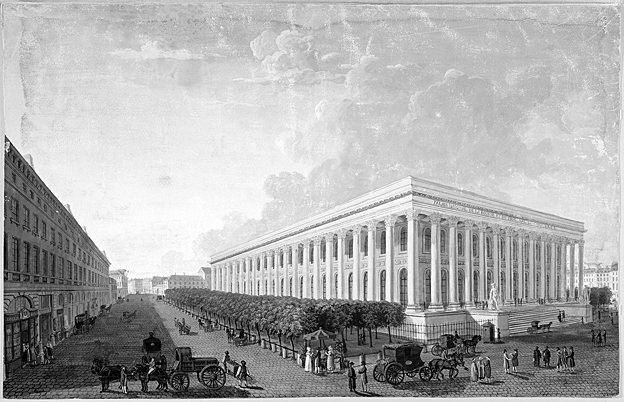

The 19th century is the century of exchange buildings, culminating in a dense network of both regional and central exchanges.94 In many places, the construction of exchanges meant that for the first time, merchants’ meetings were accommodated in a specially designed building. In many cities, monumental Basilika-Börsengebäude, as they are called in German architectural literature, became the central hub of emerging capitalism. The exchanges in Trieste (completed in 1806), St. Petersburg (completed in 1816), and the Paris Palais Brongniart (see below figure 4, completed in 1826), as well as – to cite a non-European location – the no longer extant First Merchants’ Exchange (1827) of Wall Street, New York, number among the formative examples.95

That the 19th century is the century of the exchange building is a fact that pertains, above all, to Germany and Austria. To be sure, exchange buildings existed prior to the 19th century in several of the prominent trading places, such as the Alte Börse at the Trostbrücke in Hamburg (1583), the Alte Handelsbörse in Leipzig (1687) or the kleine Börse at the Heumarkt in Cologne (1730). In Frankfurt, financial transactions were carried out in the open-air in front of the city hall, the so-called Römer.99 In Germany and Austria, however, modern, comprehensive exchange markets did not emerge until the second half of the 19th century. These, in some cases eruptive, developments coincided with the construction of many monumental exchange buildings.

In 1841, the Alte Börse in Hamburg, erected in 1583, was replaced by the Neue Börse, which served both securities and commodities trading. In 1843, the Alte Börse on Paulsplatz, the first purpose-built exchange, was opened in Frankfurt, replacing the Börsensaal in Haus zum Braunfels. In 1879, the Alte Börse moved to the Neue Börse Frankfurt, which is still in operation.100 From 1864, commodity trading also took place in the Alte Börse, and following the move to the Neue Börse, the commodity exchange settled in a building in the vicinity, until its dissolution in 1885.101

The Neue Börse Berlin was opened in 1863, replacing the meeting places previously located in the Grotte in Berlin’s Lustgarten (established in 1739) and the Alte Börse, established in 1805. By the beginning of the First World War, Berlin had become one of the most important exchanges in |the world, alongside its London and New York counterparts.102 It consisted of three departments housed in different halls but under a common roof: the stock exchange, the commodity exchange and, from 1912 on, the metal exchange.

In Austria, the Wiener Börse, designed by Theophil von Hansen (1813–1891), was opened on the Ring in 1877, where securities and commodities (with the exception of agricultural products) were traded.103 Exchange trading had earlier taken place at various locations in Vienna. This development is exemplary for many European trading metropolises. The bourse shifted from place to place before finally finding its home in a magnificent building.104 Thus, when the exchange was first opened by Empress Maria Theresia on the basis of a patent, on 1 September 1771 , it was located until 1802 on the first floor of »Zum Grünen Fassel house, at Kohlmarkt in four narrow rooms […] that were no larger than the offices of a medium-sized storehouse«.105 After having been housed in several temporary establishments, some at well-known Viennese addresses, the exchange, together with parts of the National Bank, moved into the especially designed Palais Ferstel on der Freyung.106 When the capacity of the Freyung premises proved too small, a temporary emergency building was erected at Schottenring in 1872, in which trading was carried out until the opening of the Wiener Börse at Ringstrasse in 1877. This legendary building housed the exchange until the year 2000. Trading in agricultural products, previously transacted at various coffee houses, also known as Winkel-Fruchtbörsen, found a central place in 1890 at the Vienna Exchange for Agricultural Products in Taborstrasse.107 The building bears the same motto as the old exchange in Antwerp: in usum negotiatorum cujuscunque nationis ac linguae.

The scope of the present article prohibits a more detailed discussion of the economic history of the German and Austrian exchanges from the 19th century to the present.108 Here, it must suffice to point out that the dense network of regional exchanges had all but entirely collapsed by the end of the Second World War. Only Frankfurt was able to maintain its rank as an international financial centre, while Berlin and Vienna failed to regain their pre-First World War stature. It must also be noted that after the Second World War, futures trading in commodities no longer played much of a role in Germany, moving to international commodity markets (Chicago, New York, Paris, London).109 Efforts to re-establish futures trading in Germany since then have failed, as witnessed by the abortive attempt in 1998 to introduce a commodity futures exchange in Hanover (Warenterminbörse Hannover (WTB)), where trading had ceased again by 2009. Currently, commodity derivatives are being traded on the Frankfurt Eurex, and energy derivatives on the European Energy Exchange (EEX) in Leipzig (since 2002).

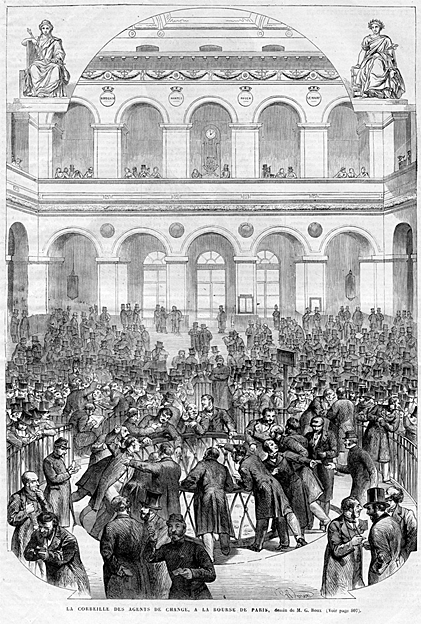

The construction of exchange buildings, some of which significantly altered the municipal structure of metropolises, represents a notable breakthrough in the process of institutionalising market places. They mark the place and time at which trading took place and, ultimately, the context in which the legal framework is to be considered.110 As Wolfram Engels succinctly puts it, the »construction of exchange buildings marks the starting point of a formal exchange organisation«.111 The close of the 18th and the early 19th century witnessed a gradual change in the design of exchanges. The buildings’ centre was no longer »empty«, as roofs were added to the courtyards, transforming them into indoor spaces geared to the specific requirements of exchange trading. The exchange interiors are now dominated by the metal corbeille (basket), as in the Paris bourse, the |Börsenschranke in Vienna and Berlin, and the octagonal pits of North American exchanges.112 It was in these rooms that the characteristic exchange sign language evolved, for which the Chicago Stock Exchange was particularly renowned.113

The corbeille, the Börsenschranke or the pit, however, not only created a spatial order of designated meeting points for different types of commodities and securities, as had been done in the Amsterdam bourse with the numbering of columns. They also achieved a market division within the exchange itself.114 The inception of this development dates back to 18th century France. In 1724, following the stock speculation orchestrated by John Law, a state-approved fund exchange was established, the number of agents de change restricted, and futures trading prohibited.115 Prior to the French Revolution, the official bourse was located at 6 Rue Vivienne in the Hôtel de Nevers, in the former premises of the Compagnie des Indes Orientales (French East India Company). According to Robert Bigo, on March 30, 1774, a three-foot-high iron barrier was erected inside the Exchange Room to mark of a space for the exclusive use of agents de change, traders and bankers.116 The area separated off by the barrier formed the so-called parquet; the space between the entrance and the barrier comprised the coulisse. In the Palais de Brongniart – the magnificent stock-exchange building first occupied in 1826 – this spatial division was maintained, with the parquet and the coulisse constituting two different markets.117 The parquet, separated off from the rest of the room by the corbeille, comprises the official market (bourse officielle) organised and mediated by the agents de change. The circular corbeille is surrounded on all sides by the coulisse (also called marché en banque) which is accessible to all and thus constitutes the free market (marché libre).

Technology, too, made gradual headway inside the exchanges.121 The introduction of telegraph services and telephones accelerated the flow of information and trading enormously. The early stages in this development, as well as the matter-of-fact spirit in which novel forms of telecommunications were integrated into the routine operations of day-to-day stock market life, are well-illustrated in the following characterisation of the Berlin Exchange of 1913:

The real nerves of the exchange are the telegraph and telephone cables. Should they malfunction, if they are ill, then the entire exchange collapses. Thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of marks, if not more, depend upon these simple cables. Thus, the Reichspost pays utmost attention to the dispatch and telephone service. The first exchange telephones went into service on 1 April 1881, from which time the number of telephones has increased year to year: the telephone cells housed in the basement in 1885 numbered 88, whereas today they are in excess of 150. Telephone lines were introduced around the turn of the last century, and the efficient broker was quick to acknowledge their great advantages: each word, clearly and distinctly audible, he promptly ceased telegraphing and used the telephone. The early stages of this transformation saw approximately six million telegrams a year dispatched from the exchange, and whereas today their number has dropped by one third, the telephone shows a perpetually upward curve.122

It was computer technology that was to definitively revolutionise the place and methods of trading. Whereas discussion as to the pros and cons of floor trading – the so-called open-outcry, as opposed to computer-operated exchange – may have still been an issue around the 1970s, in the 21st century, the latter technology has evidently asserted itself in terms of sheer practicality and cost-efficiency.123 The most recent and striking example of this is the CME Group’s termination of floor trading for commodity futures in Chicago in 2015 and at the New York Mercantile Exchange at the end of 2016.124 The Frankfurt Exchange ceased all floor trading on 20 May 2011, when trading was transferred entirely to the XETRA system.125 These are just a few examples among many. |

The globalisation of financial markets simultaneously fragments traditional financial transactions marketplaces and integrates them via electronic means. Physical marketplaces (the trading floors) are becoming obsolete, while ›virtual‹ marketplaces – networks of computers and computer terminals – are emerging as the ›site‹ for transactions. The new technology is diminishing the role of human participants in the market mechanism. Stock-exchange specialists are being displaced by the new systems, which by and large are designed to handle the demands of institutional investors, who increasingly dominate transactions. Futures and options floor traders also face having their jobs coded in computer algorithms, which automatically match orders and clear trades or emulate open-outcry trading itself.128

The digitisation of trading has had a major, even radical, effect on the form of exchange trading as we have known it since the 16th century. Not only has the form of trading been called into question, but ultimately the historically evolved institution of the exchange itself.129 What counts now is not physical access and diverse legal regulations governing admission to the exchange building, but the electronic access to a trading system.130 It is no longer the exchange that guarantees access to the gamut of liquid markets. Not unlike the old coffeehouses, we now have a multitude of (alternative) trading platforms that are difficult to define and classify, including the infamous »dark rooms«. Thus, stock exchanges are now only one among a number of types of trading sites that financial market regulation has to cover.131

When looking back over the foregoing five centuries, from the early years of the century to the reality of contemporary electronic markets, we bear witness to a most fascinating process of fundamental transformation. Everything began in the Low Countries: From Bruges we have the name, Antwerp was the first to construct, design and install the actual building and, finally, Amsterdam refined and perfected the institution. From then on, the confines of the courtyard were to physically encompass one of the central mechanisms of the market economy. However, the hectic spaces of the bourses or exchanges were emptied by technological advances, thus rendering the actual physical space of the market superfluous. To be sure, financial transactions analysis will take a different form in the future, since we can no longer simply identify the human actors within the exchange walls. Naturally, this development did not occur overnight. While globally connected markets – or, in other words, global financial cities – are certainly not an invention of more recent processes of globalisation, markets, and more specifically derivatives markets, can be traced back to the 17th-century Amsterdam exchange.132 The |18th and 19th centuries were formative in the development of a regulatory framework of exchange, and the advance of trading techniques.133 At the beginning of the 20th century, the basis for the field of financial mathematics was established in the seminal works of Louis Bachelier and Vincent Bronzin.134 Computer technology at the end of the twentieth century, eventually, led to an unprecedented leap in magnitude, speed and interconnection of markets worldwide. The rest belongs to the yet to be told future.

Illustration 1: Antonius Sanderus, Flandria illustrata, Tomus Primus 1641, Source: Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent, https://lib.ugent.be/catalog/rug01:000791673; license: CC BY-SA 4.0, unmodified

Illustration 2: Lodovico Guicciardini, Descrittione di tutti i Paesi Bassi, 1581 (Original print held by the author)

Illustration 3: Byrsa Amsterodamensis, Claes Janszoon Visscher (1587–1652), Amsterdam 1612 (Original print held by the author)

Illustration 4: La Bourse et place de la Bourse, Pierre Courvoisier (1756–1804), Paris around 1830, https://www.parismusees collections.paris.fr/en/node/101593#infos-principales, CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication

Illustration 5: M. G. Roux, La Corbeille des agents de change à la Bourse de Paris, L’Univers illustré 1865, p. 805 (Palais de Brongniart)

Illustration 6: Trading at the Berlin Exchange in the 1920s, Börse Berlin AG

Abken, Peter A. (1991), Globalization of Stock, Futures, and Options Markets, in: Federal Reserve of Atlanta Economic Review 76,4, 1–22

Anderson, Adam (1764), An Historical and Chronological Deduction of the Origin of Commerce, vol. I, London

Auer, Hans (1902)‚ Börsengebäude, in: Schmitt, Eduard (ed.), Handbuch der Architektur, Vierter Teil: Entwerfen, Anlagen und Einrichtungen der Gebäude, 2. Halbband: Gebäude für die Zwecke des Wohnens des Handels und des Verkehrs, 2. Heft: Geschäfts- und Kaufhäuser, Warenhäuser und Messpaläste, Passagen und Galerien, Stuttgart, 247–302

Baltzarek, Franz (1971), Die Geschichte der Börsenlokalitäten, in: Wiener Geschichtsblätter 26, 193–199

Baltzarek, Franz (1973), Die Geschichte der Wiener Börse. Öffentliche Finanzen und privates Kapital im Spiegel einer österreichischen Wirtschaftsinstitution, Vienna

Barbour, Violet (1950), Capitalism in Amsterdam in the Seventeenth Century, Ann Arbor

Bernhard, Georg (1933), Entry ‚Börse‘, in: Palyi, Melchior, Paul Quittner (eds.), Handwörterbuch des Bankwesens, 1st ed., Berlin

Bigo, Robert (1930), Une grammaire de la bourse en 1789, in: Annales d'histoire économique et sociale 2, 499–510, https://doi.org/10.3406/ahess.1930.1263

Blondé, Bruno et al. (2007), Foreign merchant communities in Bruges, Antwerpen and Amsterdam, c. 1500–1700, in: Muchembled, Robert, Wiliam Monter (eds.), Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe, vol. II.: Cities and Cultural Exchange in Europe, 1400–1700, Cambridge, 154–174

Braudel, Fernand (1979), Civilisation matérielle, économie et capitalisme, XVe–XVIIIe siècle, vol. 2: Les Jeux de l’Échange, Paris

Brummer, Chris, A.P. March (2013), Exchanges, in Caprio, Gerard (ed.), Handbook of Key Global Market, Institutions and Infrastructure, Boston, 401–421

Buchner, Michael (2019), Die Spielregeln der Börse. Institutionen, Kultur und die Grundlagen des Wertpapierhandels in Berlin und London, ca. 1860–1914, Tübingen

Buss, Georg (1913), Berliner Börse von 1685–1913. Zum 50. Gedenktage der ersten Versammlung im neuen Hause, Berlin

Calabi, Donatella (2004), The Market and the City: Square, Street and Architecture in Early Modern Europe, Aldershot

Calabi, Donatella, Derek Keene (2007a), Exchanges and Cultural Transfer in European Cities, c. 1500–1700, in: Calabi, Donatella, Stephen T. Christensen (eds.), Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe, vol. II: Cities and Cultural Exchange in Europe, 1400–1700, Cambridge

Calabi, Donatella, Derek Keene (2007b), Merchants’ lodgings and cultural exchange, in: Calabi, Donatella, Stephen T. Christensen (eds.), Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe, vol. II: Cities and Cultural Exchange in Europe, 1400–1700, Cambridge, 315–348

Carlson, Ryan (2013), Trading Pit Hand Signals, Austin |

Cetina, Karin K. (2003), From Pipes to Scopes: The Flow Architecture of Financial Markets, in: Distinktion. Journal of Social Theory 4,2, 7–23

Cetina, Karin K. (2012), What is a Financial Market? Global Markets as Microinstitutional and Post-traditional Social Forms, in: Cetina, Karin K., Alex Preda (eds.), Oxford Handbook of the sociology of finance, Oxford, 115–133

Coing, Helmut (1986)‚ Die Frankfurter Börse in der Entwicklung unserer freiheitlichen Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftsordnung, in: Zeitschrift für das gesamte Handels- und Wirtschaftsrecht 150, 141–154

Coornaert, Emile (1961), Les Français et le commerce international à Anvers, fin du XVe–XVIe siècle, vol. II, Paris

Davis, Mark, Alison Etheridge (2006), Louis Bachelier’s Theory of Speculation, Princeton

de Roover, Raymond (1968), The Bruges Money Market Around 1400, Brussels

Defoe, Daniel (1728), A Plan of the English Commerce, London

Denucé, Jean (1931), De Beurs van Antwerpen, in: Antwerpsche Archievenblad 6, 81–145

Devliegher, Luc (1975), Les Maisons à Bruges. Inventaire descriptif, Amsterdam

Donowell, John, Anthony Walker (1761), An Elevation, Plan and History of the Royal Exchange of London, London

Duffie, Darrel (1989), Futures Markets, New Jersey

Ehrenberg, Richard (1883), Die Fondsspekulation und die Gesetzgebung, Berlin

Ehrenberg, Richard (1885), Makler, Hosteliers und Börse in Brügge vom 13. bis zum 16. Jahrhundert, in: Zeitschrift für das gesamte Handelsrecht und Wirtschaftsrecht 30, 403–468

Ehrenberg, Richard (1892), Die Amsterdamer Aktienspekulation im 17. Jahrhundert, in: Jahrbuch für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 58,1, 809–826

Ehrenberg, Richard (1896a), Das Zeitalter der Fugger, Geldkapital und Creditverkehr im 16. Jahrhundert, vol. I, Jena

Ehrenberg, Richard (1896b), Die Geldmächte des 16. Jahrhunderts, vol. II: Die Weltbörsen und Finanzkrisen des 16. Jahrhunderts, Jena

Engel, Alexander (2015), Buying time: futures trading and telegraphy in nineteenth-century global commodity markets, in: Journal of Global History 10, 284–306

Engel, Alexander (2016), The Exchange Floor As a Playing Field: Bodies and Affects in Open Outcry Trading, in: Schmidt, Anne, Christoph Conrad (eds.), Bodies and Affects in Market Societies, Tübingen, 89–107

Engel, Alexander (2021), Risikoökonomie. Eine Geschichte des Börsenterminhandels, Frankfurt am Main

Engel, Alexander, Johannes W. Flume (2020), Bullen, Bären – und Lämmer? Auseinandersetzungen um die Börsenfreiheit und die Terminspekulation des »unberufenen Publikums« im 19. Jahrhundert, in: Rechtsgeschichte – Legal History 28, 164–181, http://dx.doi.org/10.12946/rg28/164–181

Engels, Wolfram (1980), Entry »Börsen und Börsengeschäfte«, in: Zottman, Anton (ed.), Handwörterbuch der Wirtschaftswissenschaften, Bd. II, 2nd ed., Stuttgart 1980

Entry »Börse«, in: Strauss, Gerhard (ed.) (1997), Deutsches Fremdwörterbuch, Bd. 3: Baby – Cutter, 2nd ed., Berlin

Entry »Burse«, in: Simpson, John A., Edmund S. C. Weiner (1989) (eds.), The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., vol. II, Oxford

Erickson, Rosemary, George Steinbeck (1985), The Language of Commodities, A Commodity Glossary, New York

Esquire, J. H. (1845), A Familiar Letter Touching some Exchanges in Foreign Countries (signed on Jan. 23 1647), in: A Garland for the New Royal Exchange, London

Ferrarini, Guido, Paolo Saguato (2015), Regulating Financial Market Infrastructures, in: Moloney, Niamh et al. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Financial Regulation, Oxford, 568–595

Fleckner, Andreas M. (2010), Antike Kapitalvereinigungen. Ein Beitrag zu den konzeptionellen und historischen Grundlagen der Aktiengesellschaft, Cologne

Fleckner, Andreas M. (2015), Regulating Trading Practices, in: Moloney, Niamh etal. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Financial Regulation, Oxford, 596–630

Fleckner, Andreas M., Klaus J. Hopt (2013), Stock Exchange Law: Concept, History, Challenges, in: Virginia Law & Business Review 7, 513–559, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2068574

Flume, Johannes W. (2019), Marktaustausch. Grundlegung einer juristisch-ökonomischen Theorie des Austauschverkehrs, Tübingen

Gelderblom, Oscar (2013) Cities of Commerce. The Institutional Foundations of International Trade in the Low Countries, 1250–1650, Princeton

Gelderblom, Oscar, Joost Jonker (2005), Amsterdam as the Cradle of Modern Futures and Options Trading, 1550–1650, in: Rouwenhorst, Geert, William N. Goetzmann (eds.), The Origins of Value. The Financial Innovations that Created Modern Capital Markets, Oxford, 189–205

Glaisyer, Natasha (1997)‚ Merchants at the Royal Exchange, in Saunders, Ann (ed.), The Royal Exchange, London, 198–205

Goetzmann, William N. (2016), Money Changes Everything. How Finance Made Civilization Possible, Princeton, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400881307

Göppert, Heinrich (1918/19)‚ Die Zukunft der Börse, in: Bank-Archiv 18, 219–220

Goris, Jan A. (1925), Études sur les colonies Marchandes méridionales à Anvers de 1488 à 1567, Louvain

Granichstaedten-Czerva, Rudolf (1922), Grundbegriffe des modernen Bank- und Börsenwesens, Vienna

Granichstaedten-Czerva, Rudolf (1927), Die Wiener Börse und ihre Geschichte, Vienna

Greve, Anke (2011), Hansische Kaufleute, Hosteliers und Herbergen im Brügge des 14. und 15. Jahrhunderts, Frankfurt am Main

Grünhut, Carl S. (1885)‚ Die Börsengeschäfte, in: Endemann, Wilhelm (ed.), Handbuch des Deutschen Handels-, See- und Wechselrechts, vol. III, Leipzig, 1–35

Guicciardini, Lodovico (1567), Descrittione di tutti i Paesi Bassi, Anversa

Hafner, Wolfgang, Heinz Zimmermann (2009), Vinzenz Bronzin’s Option Pricing Models. Exposition and Appraisal, Berlin |

Häpke, Rudolf (1908), Brügges Entwicklung zum mittelalterlichen Weltmarkt, Berlin

Häpke, Rudolf (1911), Der deutsche Kaufmann in den Niederlanden, Leipzig

Haussherr, Hans (1970), Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Neuzeit: Vom Ende des 14. bis zur Höhe des 19. Jahrhunderts, 4th ed., Köln

Hautcoeur, Pierre-Cyrille, Angela Riva (2012), in: The Paris Financial Market in the Nineteenth Century: Complementarities and Competition in Microstructures, in: The Economic History Review 65, 1326–1353

Hellauer, Josef (1920), System der Welthandelslehre. Ein Lehr- und Handbuch des internationalen Handels, Erster Band: Allgemeine Welthandelslehre, 3rd–8th ed., Berlin

Heller, Victor (1901), Der Getreidehandel und seine Technik in Wien, Tübingen

Helten, Josef (1922)‚ Entwicklung und Organisation der Kölner Börse (1553–1921), Cologne

Hersbach, Johann C. (1726), Verbesserte und Viel-vermehrte Wechsel-Handlung, Nuremberg

Hilbrink, August (1925), Die Warenbörse, Leipzig

Hume, David (1767), Abriß des gegenwärtigen und politischen Zustandes von Großbritannien, Copenhagen

Hunt, Edwin S., James M. Murray (1999), A History of Business in Medieval Europe, 1200–1550, Cambridge, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511626005

Israel, Jonathan I. (1990), The Amsterdam Stock Exchange and the English Revolution of 1688, in: Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis 103, 412–440

Kiliaan, Cornelis (1599), Etymologicum Teutonicae linguae, sive dictionarium Teutonico-Latinum, Antwerpen

Kirchenpauer, Gustav H. (1841), Die alte Börse, ihre Gründer und ihre Vorsteher. Ein Beitrag zur hamburgischen Handelsgeschichte, Hamburg

Klein, Gottfried (1958), Vierhundert Jahre Hamburger Börse, 1558 bis 1958, Hamburg

Koch, Richard (1881), Entry »Riskontro«, in: von Holtzendorff, Franz (ed.), Rechtslexikon, vol. III, 3rd ed., Leipzig

Kulischer, Josef (1929), Allgemeine Wirtschaftsgeschichte des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit, vol. II: Die Neuzeit, Munich

Kuske, Bruno (1953), 400 Jahre Börse zu Köln, Cologne

Lerner, Franz (1962), Hundert Jahre Frankfurter Getreide- und Produktenbörse, 1862–1962, Frankfurt am Main

Lesger, Clé (2006), The Rise of the Amsterdam Market and Information Exchange. Merchants, Commercial Expansion and Change in the Spatial Economy of the Low Countries, 1550–1630, Aldershot

Leuchs, Johann M. (1839), Vollständige Handelswissenschaft, oder System des Handels, Zweyter Theil: Staatshandelswissenschaft und Handelskunde, 4th ed., Nuremberg

Lewis, Michael (2014), Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt, New York

Lexis, Wilhelm (1898), Entry ‚Handel‘, in: Schönberg, Gustav (ed.), Handbuch der Politischen Oekonomie, vol. II/2, 4th ed., Tübingen

Lo, Andrew W., Jasmine Hasanhodzic (2010), The Evolution of Technical Analysis, Hoboken

Marechal, Joseph (1949), Geschiedenis van de Brugse Beurs, Brugge

Markham, Jerry W., Daniel J. Harty (2012), The Impact of Electronic Communication Networks on Exchange Trading Floors and Derivatives Regulation, in: Poitras, Geoffrey (ed.), Handbook of Research on Stock Market Globalization, Cheltenham, 244–303

McCusker, John J., Cora Gravensteijn (1991), The Beginnings of Commercial and Financial Journalism. The Commodity Price Currents, Exchange Rate Currents, and Money Currents of Early Modern Europe, Amsterdam

Meithner, Karl (1930), Die Preisbildung an der Effektenbörse, Vienna

Meseure, Sonja A. (1987), Die Architektur der Antwerpener Börse und der europäische Börsenbau im 19. Jahrhundert, Munich

Meyer, Gregory (2016), Trading: What happened when the pit stopped, in: Financial Times, July 6 2016

Michie, Ranald C. (1999), The London Stock Exchange: A History, Oxford

Mitchell, William J. (1996), City of Bits, Cambridge (MA)

Morgan, Edward V., William A. Thomas (1969), The Stock Exchange: Its History and Functions, 2nd ed., London

Murray, James M. (2005), Bruges, Cradle of Capitalism, 1280–1390, Cambridge

Nichols, John (2014), John Nichols’s The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth I: A New Edition of the Early Modern Sources, vol. V, Oxford

Ogilvie, Sheilagh (2011), Institutions and European Trade: Merchants Guilds, 1000–1800, Cambridge

Panster, Christian, Christian Schnell (2011), Leise Parkettrevolution an der Frankfurter Börse, in: Handelsblatt, May 23, 2011

Peiffhoven C. (1888), Die Börse in Antwerpen, in: Zeitschrift für Bauwesen 38, 161–180

Petram, Lodewijk (2014), The World’s First Stock Exchange, New York

Pevsner, Nikolaus (1976), A History of Building Types, Princeton

Pohl, Hans (1992), Deutsche Börsengeschichte, Frankfurt am Main

Prion, Willi (1930), Die Effektenbörse und ihre Geschäfte, Berlin

Puttevils, Jeroen (2015), Merchants and Trading in the Sixteenth Century, London

Richter, Katrin (2020), Die Medien der Börse. Eine Wissensgeschichte der Berliner Börse von 1860 bis 1933, Berlin

Ritter von Hansen, Theophil (1879)‚ Der Bau der neuen Börse in Wien, in: Allgemeine Bauzeitung 24, 10–12

Rückbrod, Konrad (1977), Universität und Kollegium. Baugeschichte und Bautyp, Darmstadt

Sassen, Saskia (1999), Global Financial Centers, in: Foreign Affairs 78, 75–87, https://doi.org/10.2307/20020240

Sassen, Saskia (2012), Cities in a World Economy, 4th ed., London

Saunders, Ann (1997), The Royal Exchange, London

Schacher, Gerhard (1931), Handbuch der Weltbörsen: Organisation und Usancen der grossen Effektenmärkte des Auslandes, Stuttgart |

Schaede, Ulrike (1989), Forwards and Futures in Tokugawa-Period Japan, in: Journal of Banking & Finance 13, 487–513

Scheltema, Pieter (1846), De Beurs van Amsterdam, Amsterdam

Schmoller, Gustav (1923), Grundriß der Allgemeinen Volkswirtschaftslehre, Zweiter Teil, Berlin

Schreyl, Karl Heinz (1963), Zur Geschichte der Baugattung Börse, Berlin

Schröder, Fritz (1914), Die gotischen Handelshallen in Belgien und Holland, Munich

Seiler, Friedrich (1921), Die Entwicklung der deutschen Kultur im Spiegel des deutschen Lehnworts, part II: Von der Einführung des Christentums bis zum Beginn der neueren Zeit, 3rd ed., Halle a.d.S.

Severini, Lois (1981), The Architecture of Finance, Early Wall Street, New York

Smith, C.F. (1929)‚ The Early History of the London Stock Exchange, in: American Economic Review 19, 206–216

Smith, Marius F.J. (1919), Tijd-affaires in Effecten aan de Amsterdamsche Beurs, The Hague

Spangenthal, Simon (1903), Die Geschichte der Berliner Börse, Berlin

Spufford, Peter (1995), Access to credit and capital in the commercial centres of Europe, in: Davids, Carolus A. (ed.), A Miracle Mirrored: The Dutch Republic in European Perspective, Cambridge, 303–337

Spufford, Peter (2002), Power and Profit: The Merchant in Medieval Europe, London

Stringham, Edward (2002), The Emergence of the London Stock Exchange as a Self-Policing Club, in: Journal of Private Enterprise 17,2, 1–19

Stringham, Edward (2003), The extralegal development of securities trading in seventeenth-century Amsterdam, in: The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 43, 321–344

Taeuber, Rudolf (1911), Die Börsen der Welt, Berlin

Treibl, Adolf (1908), Die Wiener Produktenbörse, Börse für landwirtschaftliche Producte in Wien, Vienna

Trumpler, Hans (1909)‚ Zur Geschichte der Frankfurter Börse, in: Bank-Archiv 9, 81–84

van der Wee, Herman (1963), Growth of the Antwerpen Market, vol. II: Interpretations, The Hague

van der Wee, Herman (1977), Monetary, Credit and Banking System, in: Postan, Michael M. (ed.), The Cambridge Economic History of Europe, vol. V: The Economic Organization of Early Modern Europe, Cambridge, 290–392, https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521087100.006

van der Wee, Herman (1993), The Low Countries in the Early Modern World, Aldershot

van Houtte, Jan (1977), An Economic History of the Low Countries 800–1800, New York

van Houtte, Jan (1981)‚ Von der Brügger Herberge »Zur Börse« zur Brügger Börse, in: Beiträge zur Wirtschaftsgeschichte, vol. VIII: Wirtschaftskräfte und Wirtschaftswege V, Festschrift für Hermann Kellenbenz, Stuttgart, 237–250

van Houtte, Jan (1983)‚ Herbergswesen und Gastlichkeit im mittelalterlichen Brügge, in: Peyer, Hans C. (ed.), Gastfreundschaft und kommerzielle Gastlichkeit im Mittelalter, Munich, 177–178

van Rooy, Max (1982), Amsterdam en het Beurzenspektakel, Aarlanderveen

Vermeylen, Filip (2000)‚ Marketing Paintings in Sixteenth-Century Antwerpen: Demand for Art and the Role of the Panden, in: Stabel, Peter et al. (eds.), International Trade in the Low Countries (14th–16th Centuries). Merchants, Organisations, Infrastructure, Louvain, 193–212

von Zesen, Filips (1664), Beschreibung der Stadt Amsterdam, Amsterdam

Weber, Max (1894)‚ Die Börse, I. Zweck und äußere Organisation der Börse, in: Göttinger Arbeiterbibliothek 1 (1894) 17–48 = Borchardt, Knut (ed.) (1999), Max Weber Gesamtausgabe, Abt. I: Schriften und Reden, Bd. 5, 1. Halbbd.: Börsenwesen, Schriften und Reden 1893–1898, Tübingen

Weber‚ Max (2013), Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, Soziologie, Unvollendet, 1919–1920, in: Borchardt, Knut et al. (eds.), Max Weber Gesamtausgabe, vol. I/23, Tübingen

West, Mark D. (2000), Private Ordering at the World’s First Futures Exchange, in: Michigan Law Review 98, 2574–2615, https://doi.org/10.2307/1290356

Whiter, Walter (1800), Etymologicon Magnum or Universal Etymological Dictionary, Cambridge

Wilson, Charles (1941), Anglo-Dutch Commerce & Finance in the Eighteenth Century, Cambridge

Wormser, Otto (1919), Die Frankfurter Börse: Ihre Besonderheiten und ihre Bedeutung. Ein Beitrag zur Frage der Börsenkonzentration, Tübingen

1 Grünhut (1885) 3 (author’s translation).

2 Lexis (1898) 255 (author’s translation).

3 Schmoller (1923) 612 (author’s translation).

4 Bernhard (1933) 105 (author’s translation).

5 Cf. Auer (1902) 250 (with [reconstructed] ground plan and cross-section of the Basilica Julia, fig. 337 sq.); for the latter two, see Schreyl (1963) 13–15. For more details on the non-existence of exchange buildings or functionally comparable locations in ancient Rome, see Fleckner (2010) 95–96 and 462.

6 Braudel (1979) 85.

7 For more details on this point, see below III, towards the end.

8 See Gelderblom (2013).

9 Cf. Schaede (1989); West (2000).

10 See Flume (2019); Engel (2021).

11 Cf. Esquire (1845) 58–59; von Zesen (1664) appended on p. 3 after the index, as supplement to p. 233 of the main text; Hersbach (1726) 55–56; Anderson (1764) 360; Whiter (1800) 89; Kirchenpauer (1841) 1–2; Kulischer (1929) 316.

12 Guicciardini (1567) 67.

13 Author’s translation, based on the German translation of the Guicciardini text by van Houtte (1981) 238.

14 Ehrenberg (1885) 448 states 1448 as the earliest documented date.

15 Hieronymus Münzer»Aliud est forum, ubi conveniunt mercatores: die boers dictum. Ubi inquam Hispani, Itali, Angli, Almani, Ostrogotti, et omnes naciones conveniunt« [cited after Murray (2005) 178].

16 See Ehrenberg (1885) 403 and 448 n. 68 with the remark that a column from Liège, captured as booty, was erected in Bruges »up de buerze«.

17 In Flandria illustrata by Antonius Sanderus, 1641, p. 271.

18 In the map drawn in 1562 by Marcus Gerards the Elder.

19 On the routes to Bruges, see Häpke (1911) 5–8.

20 Gelderblom (2013); van Houtte (1977).

21 van Houtte (1981) 244.

22 Devliegher (1975) 418; on the history of the van der Beurze family: Marechal (1949) 15–24; Greve (2011). Nota bene, the name of the family is spelled in countless variations.

23 Devliegher (1975) 418; thus Ehrenberg (1885) 447 is mistaken in claiming that »as far as the spacious and ancient house of the van der Burse family mentioned by Guicciardini is concerned, it is certain that a house called ›ter buerse‹ or ›ter ouder buerse‹ (old exchange) already existed in Vlamincstrate, Bruges, towards the close of the thirteenth century«. In reality, these are not alternative names for the same building, but separate buildings located next to each other (see main text below for more details).

24 Below the illustration can be read the following comment: »Itali quoque eundem modum hic sua habuerunt Prætoria; & nominatim Florentini & Genuenses, in quorum Prætorio hæc insciptio legitur: Hoc Ædificari Fecerunt Mercatores Januenses Brugis Commorantes Anno CIƆ CCCC XLI. CIƆ CCCC XXIX. Utrumque autem hoc Prætorium, tam Florentinorum, quam Genuensium magnifice structum, imminet Bursae Brugensi, eamque a duobus lateribus veluti claudit. (Illustrated as in the original).« (= The Italians also settled here; especially the Florentines and the Genoese, on whose house one reads the following inscription: This building was built in 1441 by the Genoese merchants living in Bruges. And another [inscription] with the same sentence referring to the year 1429. And these two houses, of both the Florentines and the Genoese, are beautifully situated on the Bruges bourse and appear to be attached on each side.) (author’s translation).

25 Devliegher (1975) 418: »Façade-écran de la maison ›Ter Beurse‹, […] datée 1453 sur une pierre de façade déplacée en 1947«. This part of the facade is shown in Devliegher’s appendix under no. 992; there is also a wooden beam with the coat of arms of the family van de Beurze dating to 1453 with illustration of the beam (no. 993) and the house (no. 995– 996) [Devliegher (1975) 419].

26 Ehrenberg (1885) 447.

27 Cf. Murray (2005) 179 n. 3.

28 According to van Houtte (1981) 240, the last bearer of the family name died in 1492; this concurs with Marechal (1949) 23 (who refers to Gailliard).

29 See van Houtte (1981) 243; by contrast, Murray (2005) 179 n. 3 claims that it was the Ter Oude Beurs.

30 Murray (2005) 179–180.

31 Cf. van Houtte (1983); Gelderblom (2013) 42–52; Häpke (1911) 9–10.

32 Häpke (1908).

33 van Houtte (1983) 182.

34 Greve (2011) 71.

35 Gelderblom (2013) 23 and 45–46; Blondé et al. (2007) 155–156; see also Ehrenberg (1885) 413 with n. 15, who points out that the Florentine merchant Francesco Balducci Pegolotti (1310–1347) in his famous merchant’s handbook Pratica della mercatura described »the Bruges ›celliere‹ as synonymous with ›Fondaco‹ and ›Magazzino‹«.

36 Gelderblom (2013) 43; Häpke (1911) 10.

37 Murray (2005) 198.

38 van Houtte (1983) 177 and 181.

39 Gelderblom (2013) 45–46.

40 Greve (2011) 71; van Houtte (1981) 237 and 242; Gelderblom (2013) 45; Ehrenberg (1896a) 81.

41 Häpke (1911) 12–13 (author’s translation).

42 de Roover (1968) 28.

43 Kiliaan (1599) 66 (author’s translation): »Borse, vulgo bursa ab ampla domo bursae sive crumenae signo insignita Brugis Flandrorum sic primum dicta«.

44 Cf. entry »burse«, in: Simpson/Weiner (1989) 683; entry »Burse«, in: Strauss (1997) 437–442; Whiter (1800) 89.

45 Seiler (1921) 212–213; Rückbrod (1977) 56–57.

46 Koch (1881) 478; van der Wee (1993) 151 with n. 32, according to whom the rescontre was a widespread practice in Antwerp in the 16th century.

47 Cf. Kulischer (1929) 316.

48 The »Old Bourse« was a relatively small arcade erected in 1515 at the back of a patrician house in Rue de Jardin; see Peiffhoven (1888) 162–163 (with illustration); Meseure (1987) 22, incl. ground plan and illustration in the appendix under no. 2f. Dominicus van Waghemakere, who went on to build the Nieuwe Beurs 16 years later, had also been the architect of this arcade.

49 For a key contribution to the history of the Antwerp bourse, see Denucé (1931); on its architectural history, see Meseure (1987) passim.

50 Peiffhoven (1888) 165–166; Meseure (1987) 22–23; Schreyl (1963) 16–17; a floor plan as well as a sketch of the interior are reproduced in: Auer (1902) 252.

51 See Calabi (2004) 176.

52 Hierzu Vermeylen (2000); Guicciardini (1567) 99, speaks of »Panto delle dipinture«.

53 Cf. in Weber (2013) 368–369 who distinguishes between »presence of goods (fairs)« and »absence of goods (exchange trading)« (italicised in original).

54 Cf on trading halls (with reproductions): Schröder (1914); on Fondachi: Calabi (2004); Calabi/Keene (2007b) 318–321; Pevsner (1976) 237.

55 See Goris (1925) 108.

56 Cf. McCusker/Gravensteijn (1991) 43–44 and 85–89.

57 On the importance of Antwerp as a money market, see Haussherr (1970) 94–96; van der Wee (1993) 196–197; on the trade of Antwerp’s merchants, see Puttevils (2015).

58 Guicciardini (1567) 67: »Ecci poi la gratiosa piazza della Borsa de gli Inghilesi, cosi detta perche la terra a lor’ contemplatione con vna bella loggietta, la fece edificare l'anno m. d. l.« (»Then there is the pretty square of the English Exchange, so called because the country erected it in 1550, and it was equipped with a beautiful little loggia«) (Translation courtesy of Salvatore Marino and Pierangelo Buongiorno). An illustration of the Engelse beurs – a courtyard framed by a U-shaped, single-story building with a covered arcade – can be found Saunders (1997) 49 (where it is erroneously referred to as Royal Exchange; for more detail, see Calabi/Keene (2007a) 291 incl. n. 15).

59 Cf. Ehrenberg (1896a) 12; Coornaert (1961) 149; van der Wee (1963) 367–368; van der Wee (1977) 331–332.

60 Goris (1925) 108.

61 Leuchs (1839) 512–513; a picture of the »Platte grond van de Beurs te Amsterdam« by Jan Caspar Philips has been preserved in the Leiden University Library; also printed in: van Rooy (1982) 15.

62 See Donowell/Walker (1761) [reprinted in: Saunders (1997) 22]; see also Hume (1767) 106; both plans refer to the Royal Exchange II. (1169–1839); for Hamburg: Klein (1958) 26.

63 Ehrenberg (1896b) 12 (author’s translation): »Man hörte dort ein verworrenes Geräusch aller Sprachen, man sah dort ein buntes Gemenge aller möglichen Kleidertrachten, kurz die Antwerpener Börse schien eine kleine Welt zu sein, in der alle Theile der grossen vereinigt waren«.

64 von Zesen (1664) 321 (author’s translation): »Auf diesem Kaufhause verhandelt man fast die ganze Welt. Alhier finden sich / neben den Hoch- und Nieder-deutschen kaufleuten / auch Pohlen / Ungern / Wälsche / Franzosen / ja zu weilen auch Indier / und andere fremde Völker. Hier redet man vom einkauf und währte der wahren / vom vertauschen der kaufmannsgühter / vom laden und entladen der schiffe / vom wechseln und widerverwechseln. Ja hier erfährt man den zustand aller Königreiche und länder der ganzen welt / auch was sich in denselben denkwürdigen begibet«.

65 Esquire (1845) 61: »If you demand of me whence cometh that common likeness of a Square, with colums and arches about it, to be seen in all Bourses, I do not pretend to decide but yet I will venture to say, that I think the Hollander took the plot from the Venetian’s Rialto, and he again from the Kanes of the Turks« (italics in the original).

66 Schreyl (1963) 17.

67 The »Old Bourse« was erected at the back of a patrician house; see Peiff-hoven (1888) 162–163 (with illustration); Meseure (1987) 22, incl. ground plan and illustration in the appendix under no. 2 f. Dominicus van Waghemakere, who went on to build the Nieuwe Beurs 16 years later, had also been the architect of this arcade.

68 In the 14th century, monastic communities are said to have rented their cloister to merchants for their sales transactions, see Meseure (1987) 26.

69 See also Schreyl (1963) 17; a humorous discussion (in verse form) of the advantages of an open, unroofed central courtyard from the pen of Thomas Gresham is printed by Ehrenberg (1896a) 82.

70 Braudel (1979) 99.

71 Spufford (1995) 309; Ogilvie (2011) 368–369; Coornaert (1961) 148; Schreyl (1963) 20 with n. 91 on the merchants’ habit of assembling in the open air.

72 Calabi/Keene (2007a) 300–301; Ehrenberg (1896a) 77.

73 For New York: Severini (1981) 31–32; For Vienna: Granichstaedten-Czerva (1927) 14–15; Baltzarek (1973) 93–94.

74 Kuske (1953) 26; Helten (1922) 2.

75 Klein (1958) 4.

76 On the influence and role of Charles V in erecting the bourse, see Spufford (2002) 51–52; Schreyl (1963) 95–96 n. 91.

77 Hunt/Murray (1999) 214.

78 For further details and references to buildings, see Meseure (1987) 100–107; Schreyl (1963) 16–20.

79 Gelderblom (2013) 32–41.

80 Defoe (1728) 192 (italics in the original); on Defoe’s economic writings, see Goetzmann (2016) 322–327, 332–337, 345–346.

81 Among the rich literature on commerce in Amsterdam are Petram (2014); Lesger (2006); Israel (1990); Wilson (1941); Barbour (1950); Smith (1919); Ehrenberg (1892); Scheltema (1846).

82 Gelderblom/Jonker (2005); Flume (2019) 206–209; Stringham (2003).

83 For a detailed account: Lesger (2006); McCusker/Gravensteijn (1991).

84 Cf. Schreyl (1963) 20; van Rooy (1982) 19–21.

85 Michie (1999) 3; on the Royal Exchanges I–III, cf. the impressive volume edited by Saunders (1997).

86 Guicciardini (1567) 67.

87 The author’s translation is based on the German translation of the Guicciardini text by van Houtte (1981) 238.

88 Cited in Nichols (2014) 144–145.

89 See Glaisyer (1997) 198.

90 On coffeehouses: Calabi/Keene (2007a) 308–309.

91 8 & 9 Will. 3, c. 32 (1697); for more details see Smith, C. (1929) 210–211; Morgan/Thomas (1969); Stringham (2002) 4–5.

92 Morgan/Thomas (1969) 26–27.

93 Stringham (2002) 7–10; on the building: Pevsner (1976) 204 incl. reproduction at 12.32.

94 Cf. the compilation by Auer (1902) 263–299; for a comprehensive overview: Taeuber (1911); Schacher (1931).

95 On Paris see Auer (1902) 270–272 incl. reproduction on pp. 359–361; on New York see Severini (1981) 31–36 and figures 38–42, and figure 43 on St. Petersburg.

96 On this point see Hellauer (1920) 236–237.

97 On comparative perspectives on these differences see Weber (1894) 17–48 = Borchardt (1999) 141–156.

98 Cf. Borchardt (1999) 143–153.

99 See Trumpler (1909) 82; Coing (1986).

100 For details, see Wormser (1919).

101 See Lerner (1962) 38, 44.

102 For details, see Buss (1913); Spangenthal (1903); Buchner (2019); Richter (2020).

103 For details, see Baltzarek (1973) passim.

104 See Granichstaedten-Czerva (1927) passim; Baltzarek (1971) 193–199.

105 Granichstaedten-Czerva (1927) 1 (author’s translation).

106 Cf. Granichstaedten-Czerva (1927) 3–7.

107 For details, see Treibl (1908); Heller (1901).

108 For details, see Pohl (1992).

109 Already predicted by Göppert (1918/19) 219 at the end of the First World War.

110 Flume (2019) 199–245.

111 Engels (1980) 57.

112 On Berlin: Hilbrink (1925) 33–34; on Vienna: Granichstaedten-Czerva (1922) 17–18; on the US: Duffie (1989) 22–23; for detailed discussion, see Engel (2016).

113 On hand signals see Carlson (2013); Erickson/Steinbeck (1985).

114 Cf. also the concise diagrammes of the division of the interiors of the Berlin, Paris, London and New York exchanges in Prion (1930) 15.

115 Cf. Grünhut (1885) 8; Ehrenberg (1883) 12–13.

116 Bigo (1930).

117 See Hautcoeur/Riva (2012).

118 Cf. Ritter von Hansen (1879) 11.

119 Granichstaedten-Czerva (1927) 20–23; Meithner (1930).

120 Cf. Flume (2019) 226–227.

121 On the historical development of technical financial analysis see Lo/ Hasanhodzic (2010); specifically relating to the exchanges of the 19th century, see Engel (2015).

122 Buss (1913) 147–148.

123 Markham/Harty (2012); Brummer/March (2013).

124 See »›Open outcry‹ is in retreat but futures and options trading-volumes surge«, Economist, Jan. 5th 2017; Meyer (2016).

125 Panster/Schnell (2011).

126 On the importance of speed in exchange trading and in particular, on high frequency trading, see Lewis (2014).

127 Cetina (2003) 7–8; Cetina (2012) 116.

128 Abken (1991) 19.

129 For the architectural perspective on this pivotal aspect, see Mitchell (1996); about the current challenges from the legal perspective: Fleckner (2015).

130 On regulating market access, see Engel/Flume (2020).

131 Cf. Ferrarini/Saguato (2015).

132 For a closer elaboration, see Flume (2019) 229–230; on global cites and global financial centers, see Sassen (1999); Sassen (2012); for a historic account on the economics of risk Engel (2021).

133 See Flume (2019) 209–223.

134 Cf. Davis/Etheridge (2006); Hafner/Zimmermann (2009); on the relevance of financial mathematics for contract law, see Flume (2019) 115–118.